Differing outcomes

Annalee Newitz's The Future of Another Timeline and Alix E. Harrow's The Ten Thousand Doors of January, Reviewed

I had plans to write out a very different newsletter today, but given today's news about the rollback of Roe v. Wade, the words evaporated. It's frustrating to see evil, corrupt, and power-hungry people take over the country and twist it into some dystopian state, and it's frustrating feeling so powerless to do anything that's meaningful.

Three years ago, I picked up a pair of books that feel like they hold some lessons for today, and rather than come up with a hot take, I'm going to re-run those reviews with a recommendation to check out both of them, and with some new thoughts.

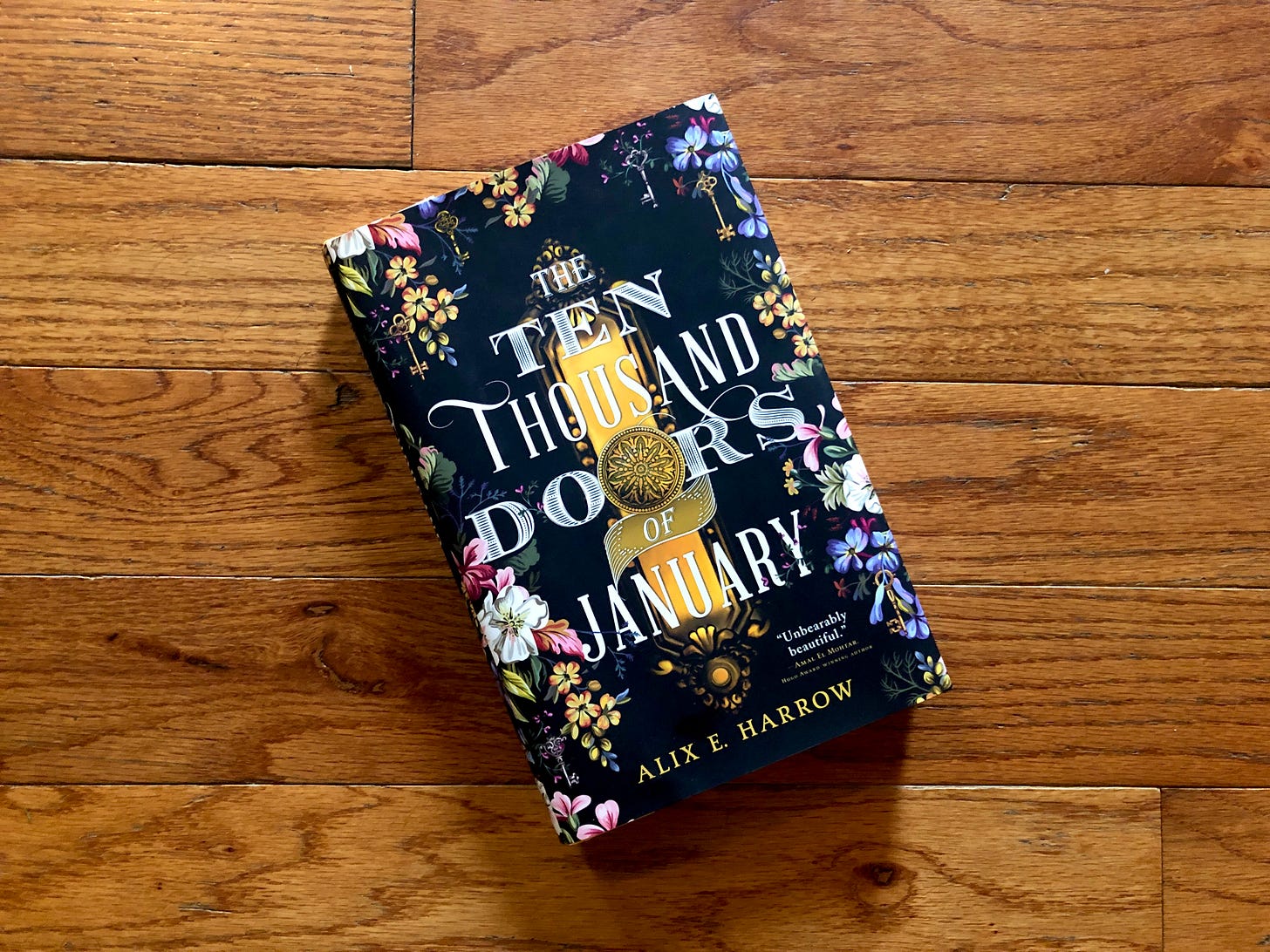

Alix E. Harrow's The Ten Thousand Doors of January

Alix E. Harrow's debut novel The Ten Thousand Doors of January is an astonishing, beautiful novel about the power of stories and the doors that they open.

Harrow introduces us to January Scaller, a young woman who's the ward of a wealthy patron named Mr. Locke. He lives in a mansion on the shores of Lake Champlain in Vermont, and has amassed a fortune and fancies himself as an amateur archeologist, collecting the curiosities from around the world to display in his home, or to sell to his wealthy friends. Locke employs her father to travel the world to find and procure objects for his collection, leaving January behind. When she's young, she accidentally comes across a door that leads her abruptly to another world, and later, discovers a book that tells of doors between a multitude of worlds, and that her own life is a key part of the story.

Speculative fiction is a genre that relies on tropes. Science fiction has its alternate reality stories, while fantasy has portal fantasies. Harrow's novel blends the two as January learns more about her past, her father, and the nature of Mr. Locke's collection. The book is part coming-of-age, part father-daughter narrative, and part thrilling adventure as January flees from her comfortable life in search of a family that she's scarcely known.

The book operates on a couple of levels. On one, Harrow examines the value of storytelling and diversity. In this particular world, she depicts stories and legends of fantastical creatures, monsters, magical abilities, and the like as a byproduct of a porous boundary between worlds: creatures and magic and stories leak through into our own. January's father (and others) is someone who tracks down stories to their origin, sometimes to alternate worlds. It's a wonderful thought: that the richness and prosperity of a creative society comes from the chaos of stories from different cultures and worlds.

On another, the novel examines the efforts people make to take advantage of the world, and to lock others out. Locke and his friends, as we find out, have benefited greatly from plundering treasures from other worlds, and seek to protect their own by shutting down the doors to other worlds. It's a tragic viewpoint, and Harrow makes the argument that it's a mindset brought on by extreme capitalism. By doing so, the book argues that a successful society is an open one, whereas a capitalistic one where a small number of people control the economy or its resources is will fail in the long run.

Those ideas power the adventure that January goes through. She's a mixed-race child, someone who doesn't quite fit in Locke's world, and upon learning of the presumed death of her father and making a couple of realizations about Locke's line of work and nature, she flees with the only friends she has in the world, trying to find her father and long-lost mother. The story takes a little while to get up and running, but once it begins firing on all cylinders, it moves. Harrow weaves together a powerful story about the nature of stories, the importance of family and love, and freedom. I don't often tear up over emotional swells in books, but this one brought out the water works by the end. It's certainly one of the best novels that I've read all year.

Harrow's book is one that's been on my mind a lot, and something that I've come to think a bit more deeply about is the idea of how power entrenches itself. The Ten Thousand Doors of January has a realization at its core: power is something that is difficult to let go of, and it's a powerful corruptor.

January finds herself in the midst of a greater, world-bending plot as an industrialist William Cornelius Locke tries to seal up the doors that connect our world to others, diminishing it in the name of keeping order and precision, trying to force us to life in a world where he and those like him are powerful.

Annalee Newitz's Future of Another Timeline

I finished Annalee Newitz's latest novel, The Future of Another Timeline, shortly after Iris was born [in September 2019), and like Harrow's novel, this was also an exceedingly appropriate one to mark the occasion of the birth of a little girl. (A disclaimer: I worked for Newitz while I was at io9, and I love their writing — take that however you will, when it comes to biases.)

Time travel is a long-standing trope with science fiction stories. It's a wonderful avenue for a thought experiment: change one thing in your past, and how does that alter your future? Films like Terminator and Looper have played with this idea in a number of ways, whether it's the T-1000 going back in time to stop its own destruction, or Joe being sent back in time to kill himself.

Newitz plays with this idea in a way that I haven't seen before: time travel is made possible with a series of deeply ancient, geological machines that allow travelers to move back and forth in time. (They can't go past their present). These machines are well-known throughout the world, and it's a common occurrence for travelers to mingle with their predecessors, studying and sometimes altering the past. Editing seems to be a difficult thing to do: kill Adolf Hitler, and someone similar shows up. It's a particularly astute view of history. When Donald Trump was elected president, many people jokingly noted that we were somehow in the wrong timeline — I still feel like this, like there is a weird thing about the world that's broken and off-kilter, waiting for a correction. What Newitz's characters realize is that while singular events are difficult to change, it's collective action that makes those changes take hold.

This story follows a pair of characters: Beth and her friends are trying to figure out life in 1992. She, along with her best friend Lizzie, kill Lizzie's boyfriend when he tries to rape her after a punk rock concert, putting her into the path of Tess, a time traveler from 2022. Tess and her allies discover that there is a group of people who are working to alter the timeline to fundamentally remove women's rights, and shut down the time machines forever to lock them into an oppressive timeline.

Newitz draws on some pressingly real-world events and figures. Her antagonists idolize a man named Anthony Comstock, a misogynistic crusader who sought to enforce obscenity laws and generally oppress women. His followers up and down the timeline have been working to edit the timeline in his image. In a bunch of ways, the book feels as though it's directly addressing the past couple of years of internet culture, particularly with movements like Gamergate and Sad Puppies, in which women were widely attacked over the years within the science fiction and gaming spheres — movements which have since been translated out into the broader public discourse. In a couple of ways, Newitz's approach reminds me of efforts for people to edit Wikipedia en masse, coming to a collective decision as to what an accepted truth or past might be.

The ultimate conclusion that Newitz comes up with is that this sort of war isn't won with a single battle or individual: it's work that requires continual maintenance and vigilance — again, lessons that are very applicable right now. The Future of Another Timeline is the book that's really needed right now — it's science fiction at its best: thought-provoking, angry, and ready to imagine a way to a better future.

Time Travel is a well-worn trope in science fiction circles, and something that I didn't quite appreciate when I first read this book is how the powerful prey on those who are different. Newitz puts a particular focus on the cruelty that's leveled against women throughout history, and how Comstock and his followers (it feels like Newitz is taking a good lesson from Margaret Atwood's approach to the Handmaid's Tale by depicting a story that's simply drawing from examples from history) operated to maintain a solid grip on the power that they had in society.

It's a good reminder here, that the stakes that so many have warned about with the overturning of Roe isn't just about reproductive rights: it's about the repercussions that an emboldened movement can bring against those who aren't like them when it comes to sexuality and race and gender. It's about power and control, and we've allowed one vital protection to get knocked out from its position.

I've got a small pile of links that have built up over the last couple of weeks, but it seems a bit insignificant to really do anything with them at the moment. I'll leave you with one though: How The Handmaid’s Tale inspired a protest movement, which I wrote for The Verge way back in October 2017. I spent a good chunk of time researching and interviewing this (And almost had it killed because it wasn't "timely" with the news cycle), by chatting with the folks who were dressing up as Handmaids to protest anti-abortion measures in states around the country.

The article ended up being an influential thing for me personally, in how I thought about costuming and the connection that they hold for bringing stories into the real world. It's something that I spoke quite a bit about in Cosplay: A History, in which I expanded on my thinking a bit, and ended up doing some additional research to explore other, earlier examples of how the women's rights movement used costumes for things like the Suffragette movement in the early 1900s. I wouldn't be surprised if we see these costumes come back out more often in the coming months and years.

Lest I forget: I have a book coming out in just a couple of days, which I might have mentioned once or twice here. (Sick of me talking about this yet? Hah!)

Briefly: here are the details on how and where to get it (Signed copies, retailers, reviews, interviews, etc.) You can actually still order books through The Yankee Bookshop in Woodstock: they didn't get their copies in on the 19th, so I'll be going down on the 27th. If you want a signed / personalized copy, here's how to get one:

I've done some other writing on this as well: here's a list of essential cons (and a video!) in the history of cosplay, while a local paper, The Times Argus / Rutland Herald wrote up a nice profile and overview of the book. I've appeared on a bunch of podcasts, and I'll specifically call out Cosplay Stitch and Seam and Stuff You Missed In History Class as being a couple of absolutely delightful interviews with some insightful questions and a good discussion.

Copies of the book are also appearing at stores. If you're in central Vermont, Bear Pond Books of Montpelier has a handful of signed copies:

This is a huge delight: I signed copies of Cosplay: A History for @BearPondBooks, a store that I’ve been shopping at for as long as I’ve been buying books. pic.twitter.com/VLmEbITO52

— Aɴᴅʀᴇᴡ Lɪᴘᴛᴀᴋ says preorder Cosplay: A History! (@AndrewLiptak) June 23, 2022

If you've got the book already (and some of you do), please consider leaving a rating / review on Amazon and Goodreads! AND: if you're looking to snag a copy, there's a Goodreads giveaway that will close in a couple of days.

And finally, there are some appearances. I'll be at Rail City Fan Fest today at noon for a talk and Q&A about the book, while Phoenix Books will host the launch event for it, in which I'll be chatting with fellow local author and friend Katherine Arden. That'll take place on June 28th at 7PM in Burlington. If you're anywhere near the area, please come! It should be a really fun time.

(Also, lemme know if you're going to SDCC: I'll be headed there in a month's time!)

That's all for this weekend. It's my birthday today, so I'm going to head out to the con in a bit and enjoy myself, and spend the rest of the weekend reading and working on our chicken coop. (The girls have gotten big.)

More book stuff next week (sorry for the flood of self-promo), and hopefully after that, we'll get back on to somewhat of a normal schedule.

Andrew