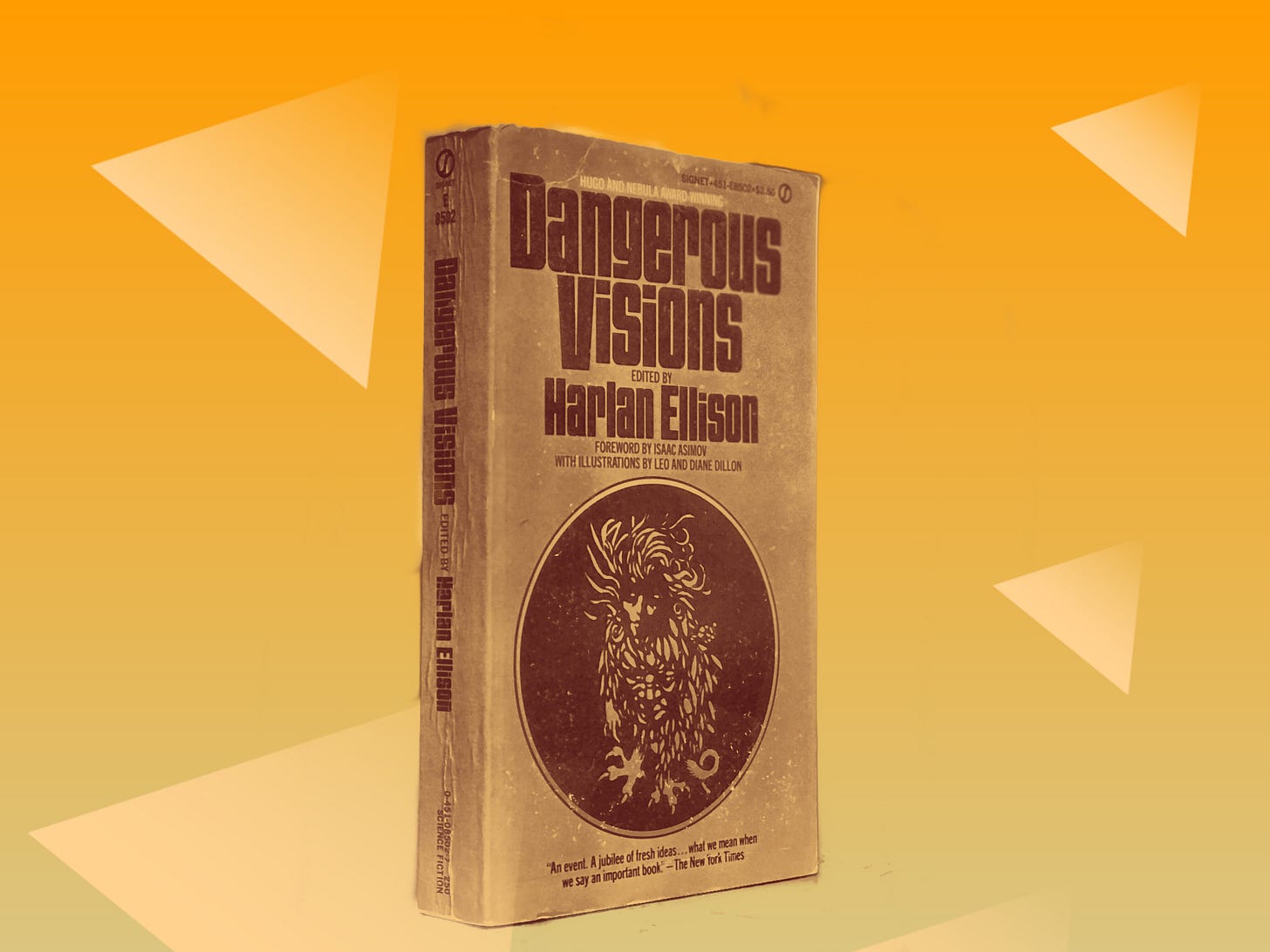

At Last, Dangerous Visions

Harlan Ellison's long-unfinished science fiction anthology might finally see the light of day

There are plenty of books that go unpublished, much to the frustration of devoted fans. George R.R. Martin’s Winds of Winter, Patrick Rothfuss’s Doors of Stone, and Scott Lynch’s Thorn of Emberlain are infamous for their tardiness, as the anticipation builds year after year. But while Martin’s next novel is the poster-child for tardiness, there’s another book that’s even more conspicuously absent from the shelves of science fiction libraries around the world: Harlan Ellison’s The Last Dangerous Visions.

And now, it looks like it’s going to finally be completed.

Ellison died in July of 2018, after years of diminishing health after surviving a stroke. When he passed, he left behind a rich legacy of storytelling and a reputation as one of the genre’s greatest — if controversial — authors. Earlier this year, his wife Susan unexpectedly died, leaving the reins of the family’s trust in the hands of writer and television producer J. Michael Straczynski, who’s best known for shows like Babylon 5 and Sense8.

Since taking over the trust, Straczynski announced that he’s been working to establish the trust and that while an estate’s assets might normally be auctioned off, he won’t permit that to happen. “There is the legacy of Harlan’s work that must be preserved and enhanced,” he wrote. “Everything that Harlan ever owned, did or wrote will be fiercely protected.”

As part of that effort, he’s working to “revive interest in his prose,” bringing on new representation to bring Harlan’s work to film, print, and television “in a big way,” teasing that there is “more to come.”

After a week of hints, Straczynski announced that he’ll be completing Ellison’s long-unfinished anthology, finally delivering the book to fans who have waited nearly half a century to read it.

Ellison is largely remembered in two ways: for writing stories as ‘Repent, Harlequin!’ Said the Ticktockman,’ ‘I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream,’ and Star Trek’s ‘The City on the Edge of Forever’, but also for his irascible, combative, pugnacious, and difficult personality. Plenty of authors have recounted their experiences with the man, through confrontations at conventions, to abrupt, late-night phone calls, to physical threats, and even an instance of sexual assault at WorldCon in 2006. In the foreword to A Lit Fuse: The Provocative Life of Harlan Ellison, David Gerrold explained that there were several different Harlan Ellisons, and that one most people saw was the “Performance Harlan”, while a smaller few witnessed the “Authentic Harlan.”

He was born in 1934 in Ohio, and was by his own admission a difficult child. Growing up on a diet of comic books and radio dramas, he explained that he was an outcast in his tiny hometown. After being expelled from Ohio State University, he became involved in the local science fiction fan scene, where he edited the Cleveland SF Society's Science-fantasy Bulletin, where he began publishing his own short stories. In the years that followed, he became a prolific author and presence within the science fiction fan community, known for his brash and outspoken nature. At the end of the 1950s, he was drafted into the US Army, where he published his debut (non-genre) novel, Rumble.

After leaving the Army in 1959, he ended up moving to California to work in the film industry, working on TV shows like Route 66, The Man from U.N.C.L.E., The Outer Limits, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, and Star Trek. He continued to publish widely, publishing some of his best-known stories, like ‘Repent, Harlequin!" Said the Ticktockman’ and ‘I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream.’

Writing in A Lit Fuse, Gerrold says that Ellison grew frustrated with the state of science fiction and some of the limitations that magazines put on their authors. He decided to put his energy into an anthology. “Not just an anthology,” Gerrold writes. “Dangerous Visions was a manifesto. A writ hammered into the doors of the church. A rebellion. Very simply: This genre is unlimited. It must not have boundaries.”

But by the 1960s, science fiction was in the midst of an identity crisis. The genre had come out of its pulpish origins and into the realm of technological and scientific plausibility, led by editors like John W. Campbell Jr. and authors like Isaac Asimov, James Blish, Arthur C. Clarke, Robert Heinlein, Frederik Pohl, A.E. van Vogt.

But as the genre began to mature as writers and editors reworked and reinterpreted tropes and introduced new themes, ideas, and political ideologies into their stories. A circle of European fans began to push against those established tropes, particularly those writing for a magazine called New Worlds, under the editorial helm of Michael Moorecock. In an editorial, he pushed against the conventions of the genre, notably calling for SF authors to abandon space:

“Science fiction should turn its back on space, on interstellar travel, extra-terrestrial life forms, galactic wars and the overlap of these ideas that spreads across the margins of nine-tenths of magazine S-F.”

It was a deliberate attempt to reform the genre and the stories that it could tell, and boost its content into more rarified, literary circles, according to Adam Roberts in The History of Science Fiction, who notes that it was a “reaction to the sedimentary weight of the genre’s backlist that new writers were beginning to feel as oppressive.”

It was a mindset that Ellison could identify with, and he lays out his ambitions for Dangerous Visions from the first sentence of his introduction. “What you hold in your hands is more than a book,” he writes. “If we are lucky, it is a revolution.”

“It was intended to shake things up. It was conceived out of a need for new horizons, new forms, new styles, new challenges in the literature of our times. If it was done properly, it will provide these new horizons and styles in formal and challenges.”

Writing in A Lit Fuse, Nat Segaloff explains that Dangerous Visions “was a reaction to the restrictions that publishers (and, in some cases, critical opinion) had placed upon genre writers."

After a couple of abortive attempts (and a loan from Larry Niven), Ellison brought his idea to Doubleday, and recruited 32 authors presently writing in the field to provide a story in 1965. Their number included Lester del Rey, Robert Silverberg, Frederik Pohl, Brian Aldiss, Philip K. Dick, Larry Niven, Fritz Lieber, Poul Anderson, Carol Emshwiller, Damon Knight, Theodore Sturgeon, J.G. Ballard, Norman Spinrad, Roger Zelazny, Samuel R. Delany, and many others. It was a dazzling array of talent, all condensed into one volume. With each story, Ellison provided a lengthy, sometimes bombastic introduction, which provide an interesting sense of a guided tour for the reader through the genre’s halls.

The book was an immediate — if somewhat controversial hit within the science fiction community. Some fans loved it, while others saw it as caustic and dismissive of the authors who came before. It left a major imprint on the genre in the decades afterwards. Gerrold noted in A Lit Fuse that it helped raise the profile of science fiction, and it pushed authors to take new chances. “I give Harlan credit for shattering the self-imposed glass walls of the genre.”

That’s not a universally-held view. Gary K. Wolfe explained to me that while Ellison’s book came at the same time as science fiction’s New Wave, Ellison’s approach to the genre was a superficial one, and that other “revolutions” were underway in other publications in the US. "Ellison was focused more on breaking perceived taboos about sex, language, etc.,” Wolfe says. “There really aren’t that many experimental stories in [Dangerous Visions], Farmer’s “Riders of the Purple Wage” being maybe the most obvious example.”

“I tend to think that the argument that authors were suddenly ‘liberated’ to write more ambitious fiction after, or because of, Dangerous Visions is pretty thin. What it did do was establish that there was a substantial book market for ambitious original anthologies.

And no doubt it benefited from Harlan’s showmanship: his voluminous introductions helped create a lot of the buzz around the anthology, and I’d argued also helped develop a sense of community, a sense that SF was doing exciting new things. The fact that most of those things had already been going on in the magazines is sort of beside the point, since magazine issues were distributed over months and years.

Harlan did provide an important focal point, and a lot of PR, for what SF was doing in the 60s. I suppose you could argue that he took an ongoing trend and made it into an event—something he may have been uniquely suited for at the time.

Author Christopher Priest, a writer who came out of the New Wave movement, was more bullish. “When word of the New Wave reached certain people in the SF world in the USA,” he told me in an email.

They jumped on the bandwagon. They sensed a new thing. Ellison was only one of these people, the most prominent and the most self-publicizing. But he missed the point!

Because he was essentially a conservative thinker, Ellison saw radical literature in terms of taboos, and taboo-busting. He wanted to shock, to disturb, to take revenge on teachers and pastors and uncles. Those were the sort of stories he touted for, and received, from mostly American writers.

Regardless, the anthology proved to be extremely popular when it was released in 1967. It sold tens of thousands of copies, several stories earned Hugo and Nebula nominations, and the anthology as a whole earned a special Hugo at the 1968 Worldcon in Oakland, California, which the convention organizers cited as “the most significant and controversial science fiction book published in 1967.”

Success demands replication. Dangerous Visions (alongside the New Wave writers) helped to solidify the market for new and original science fiction storytelling, and it helped inspire similar anthologies, not to mention speed along the careers of the book’s authors.

Ellison was — in his words — dragged, kicking and screaming into producing a sequel, Again, Dangerous Visions. His editor, Larry Ashmead, seeing the success of the original, convinced Ellison to produce another volume. Because it had “a life of its own, Dangerous Visions has forced the creation of a companion volume, bigger than the original.” Ellison explained in his introduction “Why another Dangerous Visions collection? Well, Disch is one reason. Piers Anthony is another. And the forty other writers herein nail it down finally.”

The sequel anthology appeared out in 1972, and Ellison notes that It would include a number of additional authors — 44 in all — who didn’t appear in the first edition, authors such as Gene Wolfe, Ray Bradbury, Joanna Russ, Kurt Vonnegut, David Gerrold, Piers Anthony, Gregory Benford, Ursula K. Le Guin, James Tiptree Jr., and others. “When I got into the editing of this book, I found my greatest joy was in seeing stories by new writers who were just starting to flex their literary muscles,” Ellison wrote. “An only lightly less joyful joy was in seeing older writers, who’d established reputations for doing one certain kind of story, trying something new.”

And Ellison pushed back against the New Wave label, noting that it was “as much myth as The Old Wave,” and that the two anthologies “are composed of almost a hundred New Waves, each one just a single writer in depth, and each one going its own way, against the tides.”

While Ellison says that he was reluctant to edit another anthology, it’s fairly clear from his life and personality that it as a project that he relished. He was a writer who craved attention, and the first anthology “was like a meteor hitting from the moon and taking out a cavern in the middle of Russia,” he told Segaloff. “It blew up the field; everybody talked about the New Wave, and there were fights and fights and fights and fights. There was a huge literary foofaraw, and I was right in the middle of it”

More than one person who knew Ellison described him as a deeply insecure individual, who worked establish his name and presence in the genre using every tool at his disposal, from charm, to manipulation, to threats, to badgering. In many ways, Dangerous Visions was a project that blew up and did what Ellison craved the most: established him as a major force within fandom. One hit off of that drug of attention wasn’t enough: a sequel had to do more. It had to have more writers, bring in more awards, and more attention. It was an opportunity to collect more writers, and to ensure that his name was linked to their careers and success from that point onward.

The book was well-regarded in the next award season: Ursula K. Le Guin earned the Best Novella Hugo for ‘The Word for World is Forest’, while Joanna Russ earned the Best Short Story for ‘When It Changed’ (and was a runner-up for the Hugo. Ellison earned another special Hugo for the anthology.

Two anthologies weren’t enough. In the introduction of Again, Dangerous Visions, Ellison explained that it the anthology had grown beyond what he had initially anticipated, and a third installment, titled The Last Dangerous Visions, would be released “God willing, approximately six months after this book.”

We’re still waiting.

The Last Dangerous Visions, Ellison wrote “was never really intended as a third volume.”

“What happened was that when A,DV hit half a million words and seemed not to be within containment, [Larry] Ashmead and I decided rather than making A,DV a boxed set of two books that would cost a small fortune, we’d split the already-purchased wordage down the middle and bring out a final volume six months later.

In it, he promised stories from authors like Clifford Simak, Anne McCaffrey, Michael Moorecock, James Gunn, Frank Herbert, Octavia Butler, and more. The initial release date came and went, and Ellison began collecting additional stories to expand the volume. “Now out comes Again, Dangerous Visions,” Ellison told Segaloff, “and it did even better. The problem was, I had kept on trying because everybody wanted to be in the book.”

Ellison kept tinkering, and adding additional authors. Originally intended to publish in 1972, that date slipped. He told Locus in June 1972 that he had picked up a new published, New American Library, which would publish all three books. in 1973, he again told Locus that the book had yet to be completed, but would be later that fall. That fall, he wrote a letter saying that “the book is complete” — except for the lengthy introductions and afterwords.

As of 1974, the book contained 78 stories from 75 authors. In 1976, it contained “over 100 stories.” In the years that followed, the book changed publishers again, new consulting editors came on to help, and the book’s release date slipped year after year.

In 1994, British science fiction author Christopher Priest released The Last Deadloss Visions, his exhaustive deep-dive into the troubled history of the project, exhaustively tracking the project’s non-developments.

In doing so, he found a common pattern of events: Ellison would announce via letters, articles in fanzines, or at conventions that the project was complete, save for one or two things that just needed to be completed, or some rights or change in publishers was holding up the work. Priest’s examination is well worth a read, because it’s more than a straight-up summation of the updates: he points to Ellison’s personality as a key component of the project’s ultimate failure within his lifetime: it was too big, and he simply wasn’t able to manage it. And when challenged on it, Ellison was defensive, resorting to threats or bluster to deflect attention.

“At a very basic level, the problem of [Last Dangerous Visions] is a classic example of someone biting off more than he can chew,” writes Priest. “Yet it’s easy to see how it happened: a few stories held over from Again, Dangerous Visions, a perfectionist desire to crown a project withs something even bigger and better.”

Speaking to Segaloff, Ellison chalked up the delays to the enormity of the project “My life went on. I got ill, I got married, I got unmarried, I did a lot of other things, I did books, I did movies, and I kept putting it off. It’s a huge project; I could do it, but I couldn’t do anything else; I couldn’t eat a meal.”

Most of all, Priest notes at the utter tragedy that the book represents: as the years have come and gone, the book more resembles a graveyard. Authors like Leigh Brackett, Octavia Butler, Daniel Keyes, Edmond Hamilton, Harry Harrison, Frank Herbert, Anne McCaffrey, Vonda McIntyre Jerry Pournelle, Cordwainer Smith, and A. E. van Vogt have all since passed away, and while some (or their estates) withdrew their stories, there are many stories that didn’t see print in their lifetimes, representing a loss for not only the authors, but for their fans and readers.

After Priest’s exposé on the project, Ellison continued to maintain that he would complete the introductions and see it through, saying that he hadn’t abandoned it.

But by the time he died in 2018, it remained unfinished, and it seemed as though that with his death, it would remain so.

On November 13th, J. Michael Straczynski dropped a bombshell: now in charge of Ellison’s estate, he would see the late author’s long-unfinished project to completion by 2021.

Fans have largely known what the book’s contents would be: three volumes of stories from a number of authors writing in the 1970s and 1980s, many of whom had died before seeing their stories show up in the anthologies. Under Straczynski, the book would become something slightly different.

In his Patreon post, he explains that the anthology will feature a number of those original stories, a number of stories from “some of the most well-known and respected writers working today”, and stories “by a diverse range of young, new writers from around the world who are telling stories that look beyond today’s horizon to what’s on the other side.” There’ll also be a single slot given to a new / unknown writer.

The book will also include the original art that Ellison commissioned from Tim Kirk, as well as a “one last, significant work by Harlan that has never been published, that has been seen by only a handful of people. A work that ties directly into the reason why The Last Dangerous Visions has taken so long to come to light.”

I reached out to Straczynski for this piece to ask about his plans and his thoughts on the project, but he declined to comment ahead of the project’s completion.

The elephant in the room is that pile of 100+ stories that have languished for years without being published. Straczynski says that the stories that have been withdrawn and published elsewhere won’t be in the book. Another subset won’t be included, because they “have been overtaken by real-world events, rendering them less relevant or timely.”

But Straczynski says that after those stories are removed, the remaining ones are “as innovative, fresh and, in some ways, even more relevant now than when they were first written.” Importantly, he says that the rights to those stories that won’t be used will revert back to their creators or estates, with the hope that they’ll be published elsewhere.

What’s missing out of this equation is a publisher. Straczynski says that he doesn’t have one, something that seems like an enormous complication to completing the project. He’ll be paying the authors for the project up front, and once all of the stories are in place next spring, they’ll begin shopping the project around to a publisher. Apparently, there are already publishers interested, which could bode well for the project.

Straczynski notes that he’ll be reverting the rights of the stories from the prior two anthologies as well. A quick glance through the Internet Speculative Fiction Database shows that while some authors have republished their stories in author collections or award anthologies over the years, it looks as though they were pretty much locked up. That seems like a good thing for some of those stories, and it’ll be interesting to see if they pop up online in other publications or books in the coming years.

A complicating factor to all of this is money. Straczynski says that he’s covering the costs of the anthology, as well as for the various funds needed to establish the Harlan and Susan Ellison Memorial Library and the Kilimanjaro Corporation. He says that it’s already run into the “tens of thousands of dollars,” and it seems as though that number will rise. To help defray costs, he’s opened up a dedicated tier on his Patreon page, in “return for the exclusive opportunity to see The Last Dangerous Visions come together in real-time,” where backers will get access to names of the authors, the art, and excerpts of the stories prior to its publication.

That section “Finishing the Last Dangerous Visions” will run backers $20 a month. That’s a pretty steep price: backers who jump on now will pay out at least $120 by the time April runs around — presumably well more than the finished book will cost.

I’m side-eying this a bit, given that Straczynski is looking to get a major publisher onboard for this book, which will presumably not only provide an advance for the project, but ongoing royalties (something Straczynski says will go to the establishment of the memorial library).

This is a major, legitimate criticism of crowdfunding: fans can back a project out of passion, but they’re not investors and thus not partners that will benefit from the project’s success. I don’t think that Straczynski is trying to scam fans — I have no doubt there are a lot of people who are wanting to see this book and who want to see it succeed — but it’s definitely something that could raise eyebrows from skeptics.

Given the history of the project, a healthy amount of skepticism is warranted: for years, Ellison has said that the project would soon be published, and other authors, like Martin and Rothfuss, have learned the hard way never to assign a firm release date to their unfinished works. Straczynski says that he’s working to piece together what archeological remains exist of the project, and will have to navigate rights issues, edit whatever new stories he’s acquiring, and so forth.

In an email, Priest said that he wishes Straczynski luck with the project, but that he’d warn him to be “extremely careful, because the rights position on most of the remaining stories will be unclear.” Some authors who were set to appear in the title weren’t aware of Straczynski’s work on the project, others had no comment.

Straczynski could very well complete the project: compile the remaining stories and whatever introductions Ellison had left behind, find a publisher, and deliver it to fans. He could also find a minefield of author estates, or a pile of stories that authors don’t want to be published, given that they were written decades ago. We could find ourselves in the situation where the process continues to drag on for years.

So where does this leave us?

As Straczynski notes, it’s been nearly half a century since the book was originally supposed to hit bookstores. Can an anthology designed to highlight the best and brightest of the science fiction genre retain that focus decades later, or will it be a mere historical curiosity, something that fans have long waited to read?

The original Dangerous Visions anthologies were projects designed to highlight the boundless potential of the science fiction genre, pulling together a snapshot of the writer’s community at the time, coupled with extensive commentary that provided readers with a keen insight into the trends and individuals in the field.

As the years dragged on, the urgency behind The Last Dangerous Visions began to evaporate. As Priest noted in his work, the interest around the book “has been created by Mr. Ellison himself,” boosting the profile and brilliance of the stories that were to be included.

“Interestingly, none of this has come from the writers themselves: certainly, the ones I have spoken to have been extremely modest about their work, and in many cases, have been noticeably defensive about it, because they feel that what they sold to Mr Ellison no longer represents their best work.”

Furthermore, Priest notes, “By not breaking out of the commercial idiom, by a focus on effects and sensation, it looks increasingly dated. I hate to think what contemporary young readers would make of those stories now, with their assumptions about women, race, gender, etc.”

Published as-is, it increasingly felt as though The Last Dangerous Visions would deliver a whimper, rather than a band within the fan community. Fandom has changed over the course of a half-century as writers enter and exit the field. Anthologists such as John Joseph Adams, Ellen Datlow, Gardner Dozois, David Hartwell, Ann and Jeff VanderMeer have produced their own excellent anthologies that explore the various tropes, themes, subgenres, or history of the genre, pushing the genre’s boundaries beyond Ellison’s books.

Straczynski’s book will incorporate some part of the original package of stories that Ellison collected. He hasn’t said what stories will be included, but it’s safe to assume that anything that’s appeared elsewhere won’t be included. What he’ll produce won’t be Ellison’s Last Dangerous Visions, as he intended it: readers likely wouldn’t have been drawn to the anthology just for the stories alone, but for the commentary that Ellison would have provided.

This book, in all likelihood, will be a tribute to Ellison — Straczynski carrying his last, unfinished project across the finish line to put one troubled legacy to rest. It seems that he’s aware of the problems surrounding the original contents of the book, and by including new stories in the spirit of the original, it’ll be a book that will hopefully rekindle some of the anthology’s core motivation: to push the boundaries of the genre.

This Last Dangerous Visions will likely sell well, if anything, because of the speculation and mythology that’s grown up around it. How the book will ultimately turn out will depend on a couple of factors: the authors and stories that Straczynski retains, the ones that he brings in, and how well how he reconciles the book between the era of the 1970s and the 2020s.

Hopefully, if the book finally sees print, it’ll be more than a book that exists only to close out Ellison’s legacy or which will appeal only to his diehard fans, but a volume that goes back to what Ellison intended with the original: a book that “shakes things up,” and which explores “new horizons, new forms, new styles, new challenges in the literature of our times.”

As always, thank you for reading. When I turned on subscriptions for this newsletter earlier this year, I took out my notebook and wrote down a long list of topics that I’d like to eventually write about.

Years ago, I wrote for Kirkus Reviews about the history of science fiction, and The Last Dangerous Visions was one of those topics that I never quite got around to doing. Straczynski’s revival of the project represented a good opportunity to revisit that idea, and I’m as interested as anyone to see what ultimately happens here.

I had a lot of fun researching and writing this over the last couple of days. Huge thanks to Gary K. Wolfe, Christopher Priest, Larry Niven, and a couple of others who commented for this piece.

This is a subscriber-locked post, which means that it’s your support that helped make it possible: thank you. Please feel free to pass this piece along to anyone you think might be interested! Given the profile of this project, I’ll likely unlock it at some point for the rest of the subscriber pool and general public.

Andrew