Averting Orbital War, Bookshelf Duplicates, and Mando Fans

Hello!

Thank you to everyone who entered the giveaway contest. In total, we raised $225. I’ve notified giveaway winners, and I’ll be shipping their books out to them shortly. Thank you! If you happen to buy a new book in the next couple of weeks or months, consider buying from your local indie store. I just ordered a copy of P.W. Singer and August Cole’s Burn-In, which is set to come out in May.

I’ve been plugging away with work and trying to keep my children occupied in the meantime. We’ve settled into a rough routine here at home, bouncing them between activities, school work, video chats, and so forth. Going to the grocery store remains a surreal activity. We’ve been spending more time outside in the yard, and have been working on other projects — I’m halfway through building a Little Free Library for my yard right now, something I’ve wanted to do for years.

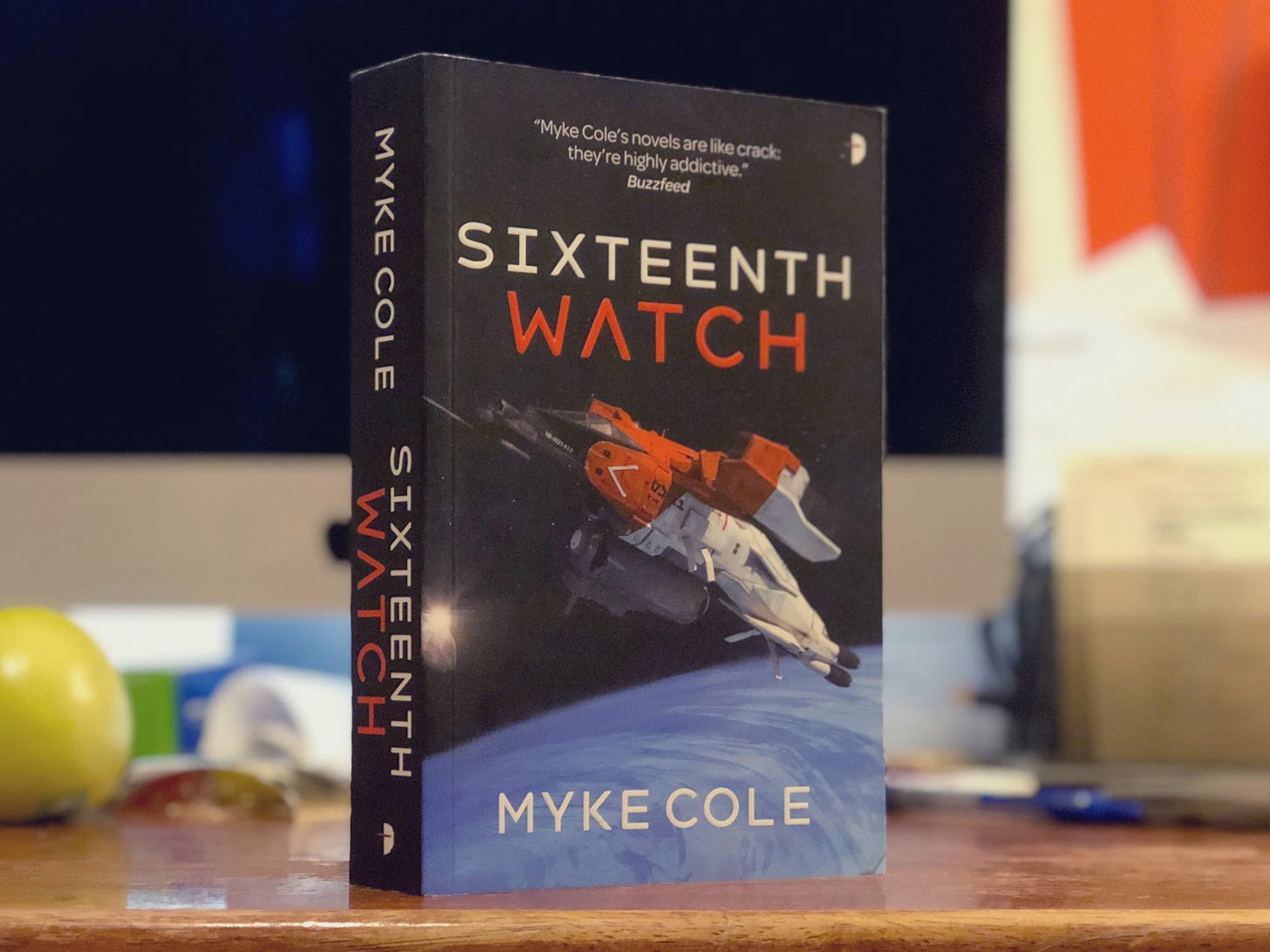

Up ahead, a look at Myke Cole’s latest novel Sixteenth Watch, some thoughts on duplicate books, and a roundup of some interesting articles that you might like to read.

Averting Orbital War

In the years after the Second World War, tensions between the United States and Russia were on the rise, with each side eying one another warily as they worked to build up stockpiles of nuclear warheads and the vehicles with which to deliver them. Locked in an arms race to develop the most effective means to deliver atomic destruction across the world, they developed a new delivery method: the Intercontinental Ballistic Missile.

In doing so, they launched the space race. The US and USSR announced their intentions to set foot on the moon, a symbol of their technological advancement, and a symbolic destination for the ultimate high ground in any Earth-bound conflict. Whoever appeared to have control of the Moon would have a significant leg up in the slow-burning conflict.

But while Astronauts and Cosmonauts captured the attention of the world’s public, another battle played out within the US military: which service would ultimately be in charge of the country’s ICBM stockpile, and by extension, would control vast amounts of political capital in the halls of Washington D.C.?

That conflict underlines the action in Sixteenth Watch, the latest novel from author Myke Cole. Cole, a former officer in the Coast Guard reserves, takes his service into space as tensions between the United States and China begin to flare up as both countries vie for control of the Lunar surface. Amidst this backdrop, the Coast Guard works to maintain its mission and presence in orbit alongside the US Navy and Marine Corps. While military science fiction has a long and rich history within SF circles, there’s always been a tendency for authors to wax poetic on big-picture political theory, from the value of citizenship to a soldier’s responsibility to a country that they might not otherwise recognize or feel that they’re a part of. With Sixteenth Watch, Cole uses the novel to examine the value of honest, straightforward leaders, as well as the importance of the Coast Guard’s central mission: “to ensure our Nation’s maritime safety, security and stewardship.”

Sixteenth Watch is set at some point in the reasonably near future: the US and other nations have established a regular presence in orbit, while civilian miners have begun mining the lunar surface for Helium 3, a (as of now, theoretical) energy source for fusion reactors. As the novel opens, US and Chinese miners have been engaged in some low-level conflicts as they encroach on one another’s territory; encounters that are threatening to escalate to much larger conflicts as each country’s forces begin to intervene.

It’s in this environment that the Coast Guard finds itself wedged between its larger military siblings: it’s tasked with maintaining some level of law and order in Earth orbit in a role that largely maps to its present standing: stopping smugglers, ensuring that vehicles are operating in compliance of safety regulations, and performing rescue missions as needed. Commander Jane Oliver commands a space-born cutter, and is frustrated by what she sees as an encroachment of her mission by her counterparts in the US Navy — whose ranks include her husband, Tom. In an early skirmish, she and her SAR-1 crew crash, losing two men, and she witnesses her husband’s death when a Chinese ship collides with his ship. She is cycled back down to Earth, where she plans on retiring quietly.

As is wont to happen, Oliver finds herself ordered back into orbit nearly a year later as the Coast Guard’s leadership finds an opportunity to try and boost the service’s profile against that of the US Navy within governmental policy circles. The stakes are high for the service: the Navy, she learns, is working to push out the USCG from space, relegating it back to the oceans from which they both came. The service hopes that a good showing at an annual military skillset competition — Boarding Action — will help demonstrate their value in orbit, and help ensure that space won’t become a perpetual war zone. “We’re going to stop a war … by winning a game show?”

Boarding Action, it seems, has become a highly popular reality program for US viewers, who tune in by the millions. All of the major US branches and law enforcement agencies sent their best and brightest (including, funnily enough — the US Postal Service Inspection Service) to compete. Oliver’s job is to whip the Coast Guard’s team into shape to make a good showing. She’s made a Rear Admiral, and is promised a retirement on the Moon, where she can help her prospector daughter get her own mining business up and running.

Sent into orbit, Oliver finds herself stuck between competing missions and intentions. Her team — SAR-1, is now part of SPACETACET (Space Tactical Law Enforcement Detachment), is comprised of a group of misfits — her XO Lieutenant Commander Wen Ho, Chief Brad Elgin, Petty Officer Connor McGrath, Boatswain's Mate First Class Naeemah Pervez, and Machinery Technician Third Class Everistus Okonkwo, are all excellent at their jobs, but they’ve never worked together, and are still reeling from the earlier conflict that cost their friends lives. It’s Oliver’s job to get them functioning as a cohesive unit, a challenge at the best of times.

But Oliver also takes to heart the bigger mission at hand: to ensure that the Coast Guard proves its worth in orbit by ensuring that there’s a space for law enforcement and rescue capabilities, and by extension, that the people in orbit aren’t trigger-happy operators looking for a fight. This, along with Oliver’s no-bullshit attitude, lands her in trouble as she brings her people into the field for training, responding to interception and emergency calls, which put her into the path of her Naval rivals.

It’s here that Cole’s use of the Coast Guard makes a lot of sense. The inter-service rivalry that he portrays is reminiscent of the fights for power amidst any technological achievement. The US Army and US Navy worked to wrest control over aviation in the pre-World War II years, while the Army, Navy and newborn Air Force fought over who would have control over missile development and oversight. In Cole’s world, the US Navy has a good argument to make for taking the justitiction in space, and he makes a good argument that in a domain where the stakes are incredibly high, the Coast Guard’s mission is more important than ever, because any conflict in space could have devastating consequences — not only in space, but back on the surface of the Earth as well.

If you’ve followed Cole on Twitter, you might have seen him voice his frustrations with a sort of cult-of-worship directed at the military, putting service members on a pedestal. He’s pointed out his frustration at civilians and police who have adopted military or military-style clothing and equipment in their everyday lives (TactiCool), and how the hero-worship Sparta forms a distorted image of our history. Essentially, Cole’s point is simple: service members do extraordinary things, but it’s a job they signed up for, and that despite their sacrifices, armies are made up of regular people.

That line of thought is central to the action in Sixteenth Watch. While the book is about a (now) fantastical premise that’s years away, it’s ultimately a story about a group of women and men who simply want to do the best by their country, and that the bigger policies and direction of the nation’s armed forces comes down to those service members. Oliver seeks to lead by example, going out on missions with her crew, and pushing them to work as a team, even as they hit setback after setback.

Ultimately, Sixteenth Watch fits nicely within the growing body of what writer August Cole calls FicInt. Myke Cole (no relation to August) puts together a near future geopolitical power struggle that seems more plausible by the day, one that should be familiar to anyone who’s read Ghost Fleet. But at its core, Cole points out that while technological and technical advancements will be a part of any type of future war, it’ll be the character and drive of the people waging it that will make all the difference.

Mando Fanservice

I’ve got a new feature up on Polygon about The Mandalorian Mercs, and how the fan obsession with the Mandalorians have helped nudge that particular subculture into a more prominent place within the Star Wars universe. I interviewed the founder of the Mandalorian Mercs, as well as some Mandos and people from Boba Fett fandom. I’m really happy with how this came out, and I’m glad to see it online.

You can give it a read here.

Cloned Copies

I read quite a bit, and as a result, I’ve accumulated a number of books over the years. I have bookshelves in just about every room in the house, sorted out by category (science fiction / fantasy, SF/F nonfiction, Star Wars, military history / history, science nonfiction, fiction, etc.) Space is … a premium, and I’ve gotten very good about regularly pruning those shelves, trying to make some space for the books that I do want to keep.

While I was looking across my shelves, I realized something interesting: there are a handful of books that I have duplicates of, despite those space constraints. I’ve been thinking a lot about the books that I do hang onto, and what they mean to me personally.

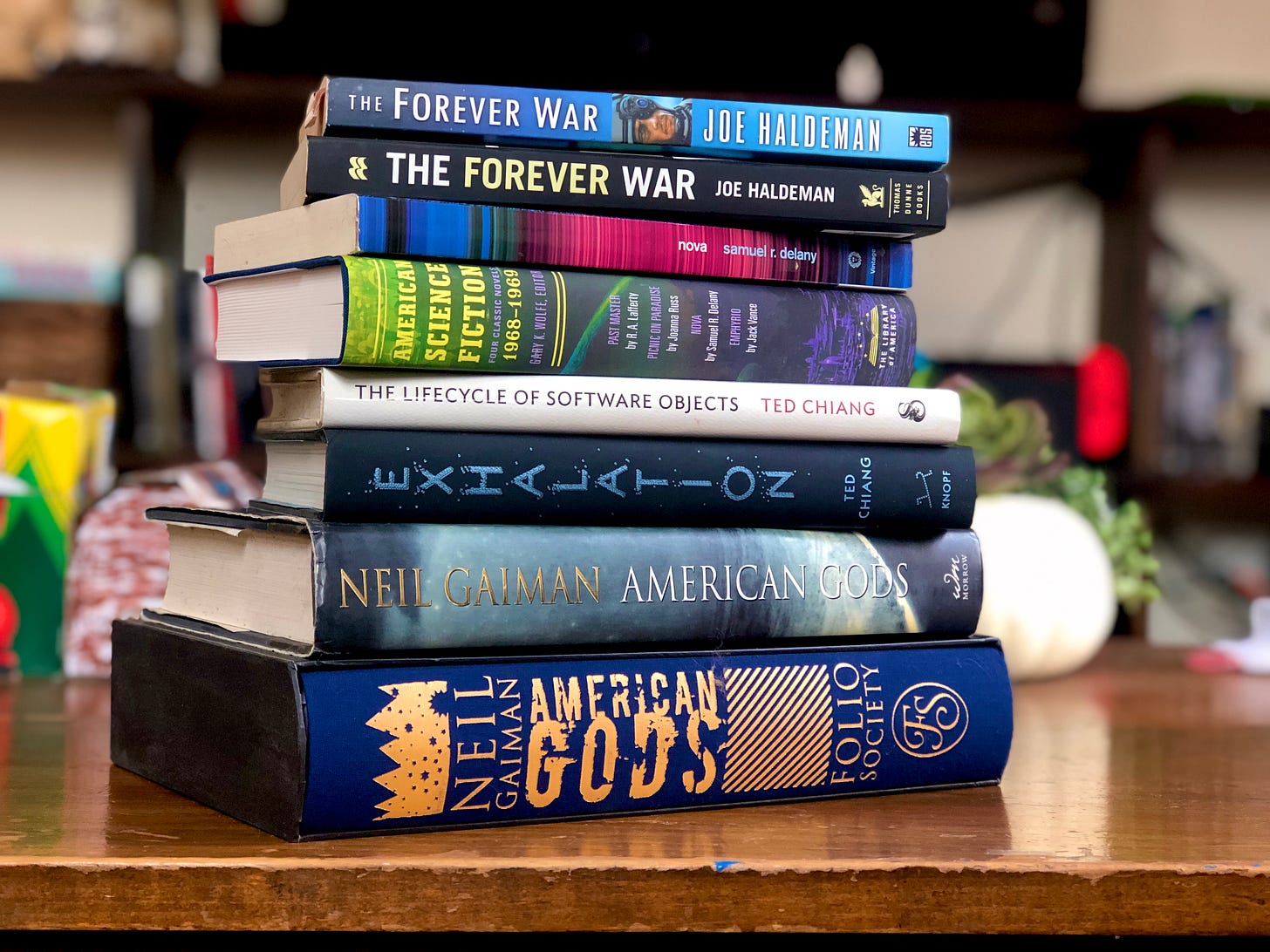

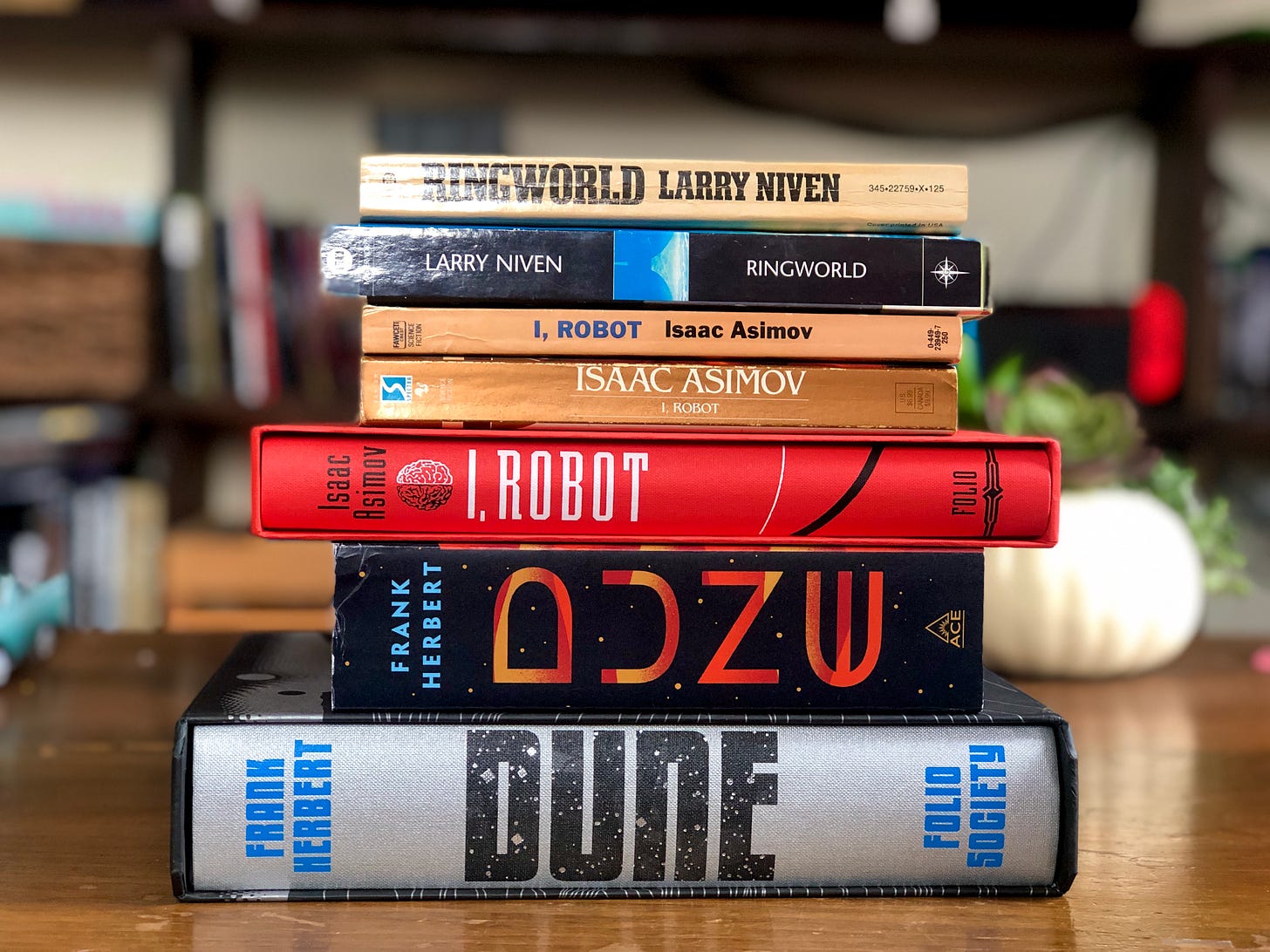

A quick scan finds the following duplicates:

- I, Robot by Isaac Asimov. I have three copies of this: the mass market paperback that I read as a kid, a copy of The Folio Society’s edition from a couple of years ago, and a really old edition I picked up at a used bookstore in Toronto.

- The Lifecycle of Software Objects by Ted Chiang. I’ve got a copy of the hardcover of this book from Subterranean Press. The novella also appeared in his recent collection, Exhalations.

- Nova by Samuel R. Delaney: I’ve got a copy of the Vintage edition, as well as a copy in Gary K. Wolfe’s 1960s science fiction omnibus from Library of America. The Vintage copy is signed from when I met him at ReaderCon… probably back in 2008?

- American Gods by Neil Gaiman. Two copies of this: there’s the battered first edition that I picked up at the long-closed Northfield Bookstore, which I read in high school. Then there’s the Folio Society edition that I picked up a couple of years ago after interviewing artist Dave McKean.

- The Forever War by Joe Haldeman. Two regular copies of this. One is the Eos trade edition from 2003, the other is the more recent trade paperback from Thomas Dunn, with an updated cover and introduction from John Scalzi. The Eos copy is signed, but I like the cover of the former much better.

- Dune by Frank Herbert. I recently got the latest mass-market edition of Dune (along with the rest of the series), along with The Folio Society’s edition.

- The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin. Two copies of this. Folio edition, while the other is in a volume of Le Guin’s Library of America Hanish omnibus.

- The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin. Same as above.

- A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula K. Le Guin. Same as above, different omnibus: I have a copy of Saga Press’s The Books of Earthsea.

- Ringworld by Larry Niven. I’ve got an original paperback, which has art by Dean Ellis (which is probably my favorite cover of all), along with a copy of Gollancz’s SF Masterworks trade paperback edition, which also has a fine cover. (Most of the book covers for this book are terrible.)

- The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien. Three copies of this one. I’ve got a mass market from before the Lord of the Rings movie trilogy with cover art by Ted Nasmith. I’ve also got the oversized hardcover edition from Harper Collins, and an edition from 1966 with the classic blue-green-black-white cover.

- The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien. I’ve also got three copies of this trilogy. Mass markets with art rom Nasmith, as well as the oversized Harper Collins hardcovers in a boxed set. Then I’ve got an omnibus edition from Houghton Mifflin that features some movie art. (I’ve owned and given away a couple of these over the years).

I think that’s pretty much all of them (there might be a random mass market here or there that I have duplicates of), and there a couple of things that stand out. The first is nostalgia or some sort of personal connection to a story. I have signed copies of books by Chiang, Delaney, and Haldeman, and I remember those conventions where I got them signed. (Chiang’s is funny: I bought the book from a dealer at ReaderCon, turned around, and he was standing *right there.*). It’s also the case for why I’m holding onto my older edition of I, Robot and American Gods and Lord of the Rings. These are books that are deeply personal to me, and I’m very attached to these particular volumes, even though I have other copies that are slightly more durable.

The second thing that stands out is quality / uniqueness. I don’t really see myself as a collector, but I like having nice-looking books that stand out on the shelf. That’s generally why I have a bunch of Folio Society editions that I’ve picked up over the years: they’re beautiful volumes, often with some unique introductions or forewords. They’re also nicely constructed: I don’t think that we’ll see them succumbing to acid burning in the coming decades. Beyond duplicates, I’ve picked up other boxed sets and particularly unique editions, not just because they look good, but because they condense space and are of a higher quality.

Another element here is cover art. It’s why I’ve held onto two copies of Haldeman’s book, Lord of the Rings (For years, I thought I had ditched those copies, and deeply regretted it, to the point where I was scanning used bookstore shelves for similar editions. When I rediscovered them in a box last year, I was overjoyed.) and Ringworld.

Ultimately, the desire to hold onto these editions outweighs the space considerations. I’d count all of these books as favorites, and something that I’d read again if the mood struck. Looking at them in this light, I’ve begun looking at my bookshelf a bit differently: not so much as a way to simply store books, but a reflection of my tastes in the genre.

And maybe a little aspirational optimism for what I’d *like* to read someday.

Currently Reading

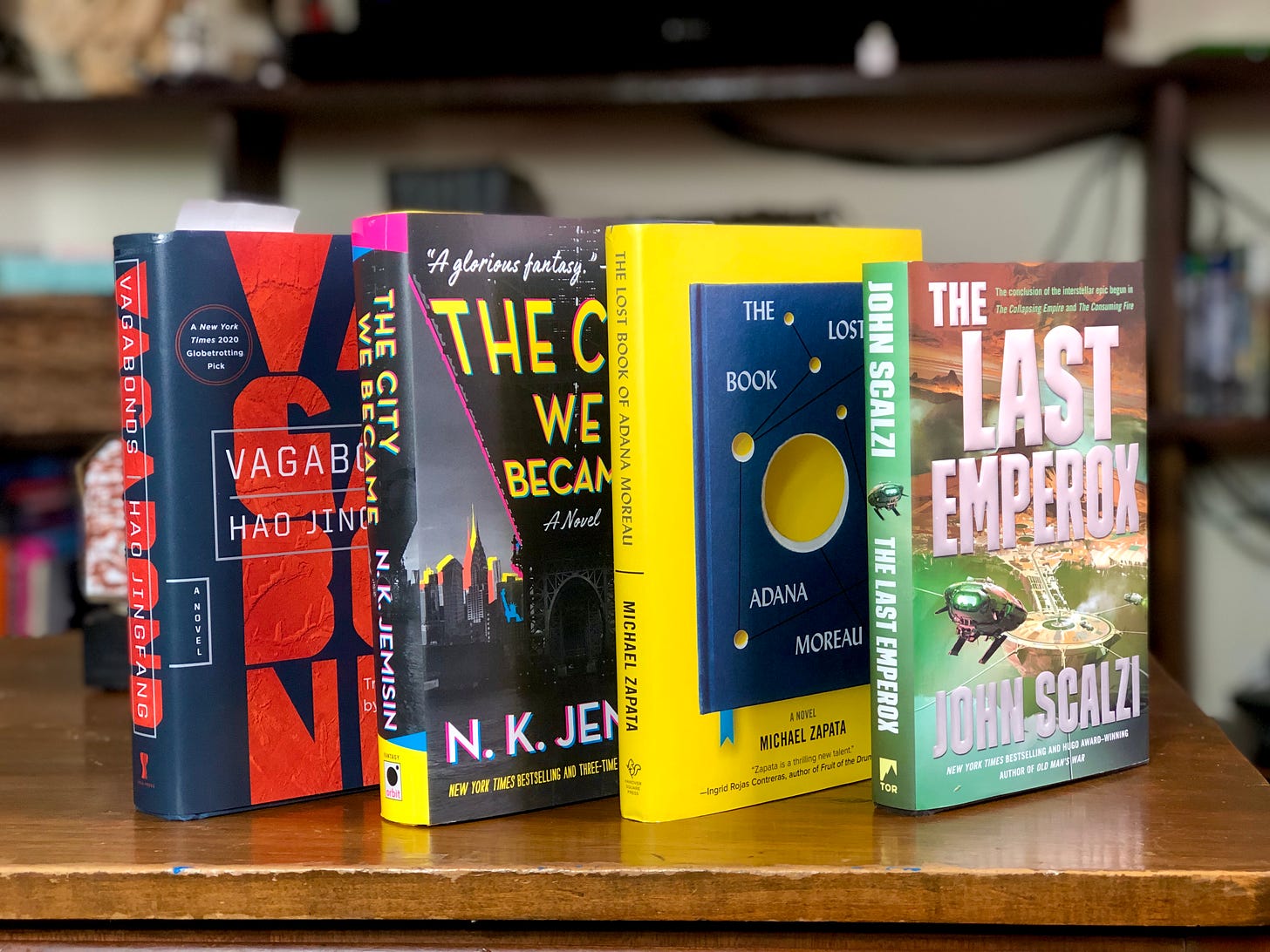

I finished two of the books that I was reading in the last couple of weeks: The Last Emperox by John Scalzi and The Lost Book of Adana Moreau by Michael Zapata. Scalzi’s books are generally fun, and this one is no exception, although I come away from this trilogy feeling like he left a lot on the table. I’ll have some more thoughts on it in the next newsletter, I think.

Zapata’s' debut on the other hand, was a wonderful read. It’s a really interesting novel about family and the power of stories, as well as a neat look back at a somewhat alternate history of the genre.

I’m now reading two books that I’ve had on my to-read list for a long while: The City We Became by N.K. Jemisin and Vagabonds by Hao Jingfang (translated by Ken Liu). In the case of Vagabonds, I decided to sign up for Libro.fm, the indie bookstore alternative to Audible. I figure I’ll give it a try to see what their selection is like: I suspect I’ll be switching off from Audible (Their originals are neat, and I like the concept, but honestly, they’re not really productions that I listen to. A topic for another newsletter, I think.)

Further Reading

- Alix E. Harrow interview. Eliot Peper interviewed Alix E. Harrow (The Ten Thousand Doors of January) and her debut novel. It’s an interesting talk about where the book came from, parallel worlds, and tropes.

- Carbon Economy. Kim Stanley Robinson has a new column up on Bloomberg Green, about how governments need to make the state of the environment an economic priority.

- First Look at Dune. Vanity Fair has a first look at the upcoming adaptation of Dune, and man, it looks fantastic. I’m really digging the costumes.

- Folio’s A Clash of Kings. The Folio Society released the next installment of George R.R. Martin’s A Clash of Kings, and like the first installment, A Game of Thrones, it’s utterly gorgeous. I interviewed Jonathan Burton about his artwork.

- Golden Trilobites. Atlas Obscura has a fascinating look at the trilobites one can find in upstate New York: Triarthus specimens that have been pyritized. They’re gorgeous, and good incentive to do some fossil hunting this summer.

- Pandemic reality. Charles Yu (Interior Chinatown) has a really interesting post in The Atlantic about the present state of the world, the unreality of the situation we find ourselves in.

- Plight of Bookstores. Over on Tor.com, I took a look of how bookstores are coping with the pandemic. The short answer is… not well. Stores can’t simply change their entire model overnight, and the longer that the crisis goes on, the worse off they’ll be.

- Vermont’s First Hugo. Katherine Arden earned a nomination for her Winternight trilogy for the Best Series Hugo Award. She appears to be the first Vermonter (living in the state) to earn the award, although Piers Anthony (who also lived here) did score a couple of nominations in the 60s/70s. I wrote about it for Seven Days, our local alt-weekly.

That’s all for now. The comments on this newsletter are open — if you want to continue the conversation, feel free to weigh in. I’d love to know what you think.

As always, thank you for reading: I always appreciate the time folks take to read, and the comments that I’ve gotten. (I owe some of you emails back). If you liked this, please consider sharing it on social media, or by forwarding it along to a friend.

Andrew