Cyberpunk's power came from global dystopian politics

It might look like the 1980s, but we're still living in it

CD Projekt Red’s Cyberpunk 2077 comes out today, and judging from the trailers and early reviews, it’s a game that leans heavily into the ‘80s styling for the subgenre: lots of neon, people with tons of body augmentations, and lots of over-the-top violence.

I’m looking forward to playing the game — it’s currently sitting installing some updates on my Xbox — but it’s gotten me thinking a bit about the nature of cyberpunk and how the world that it depicted has ended up pretty close to ours.

Science fiction has always been interested in the intersection of technology and humanity: stories of robots go back as far as the 1860s with books like Edward S. Ellis’s Steam Man of the Prairies, and later pulp stories about murderous robots in space before transitioning to treating them almost like household appliances, as in Lester del Rey’s ‘Helen O’Loy’ or Isaac Asimov’s Robot stories. While computers were a thing (a room-sized thing) in the real world, authors often still envisioned them in one of two ways: as an object to be used, or as a super-powered entity that figures into the plot.

Missing from that equation until later was how authors envisioned computers impacted the world. There’s Frederik Pohl’s famous quote about how some works really get a handle on that potential: “A good science fiction story should be able to predict not the automobile but the traffic jam.”

In many ways, cyberpunk anticipated the impact that computers would have on the world — not as objects, but as tools on which connected everything from multinational conglomerates, communications, and even dreams and digital realities.

The origins of the subgenre emerged out of the tail end of the New Wave movement that took place in the 1960s and 1970s — a stylistic push against the established and conservative conventions of the larger science fiction genre. Broadly, it pressed authors to think differently about depicting the future, breaking from the harder sciences and looking more at the sociological and cultural lens. Out of that period, a handful of authors published works that serve as a thematic ground floor for what was to follow: powerful corporations, human / computer cybernetics, and so forth, such as James Tiptree Jr.’s ‘The Girl Who Was Plugged In’, Alfred Bester’s The Stars My Destination, and Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

If the New Wave drew on the progressive movements of the 1960s/70s, the political tides that brought President Ronald Reagan and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher to power and the rapidly changing world of computer technology provided plenty of fuel and inspiration for a new crop of rising authors.

In her chapter in Science Fiction: A Literary History, Sherryl Vint notes that the economic overhaul that Reagan and Thatcher enacted in the 1980s brought about an entirely new worldview: one in which the role of centralized governments was rolled back through waves of privatization and deregulations, all while the world’s commerce was beginning to go global. “Economics,” Vint writes, “is as important to cyberpunk’s emergence as IT.”

This was helped by a surging personal computer movement. Computers began to enter homes and businesses in the late 1970s, where they began to find new uses. In 1977, Jerry Pournelle was the first author to write a novel on a computer, and from there, their uses tore off in all sorts of new directions.

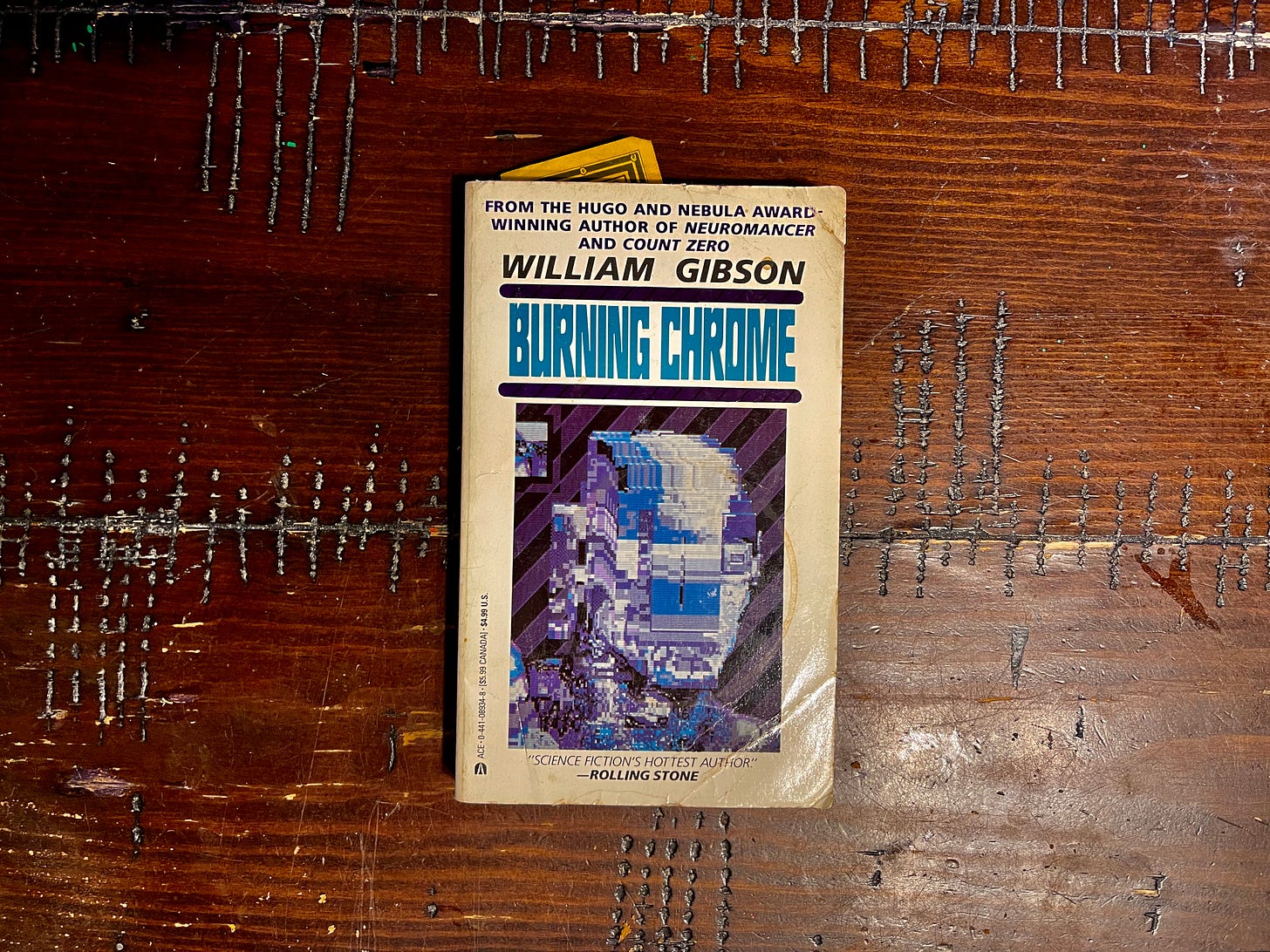

As a genre, science fiction was well suited for these massive changes. The first use of the term “cyberpunk” comes from Bruce Bethke’s short story by the same name, which appeared in Amazing Stories in 1983, about a group of teenage hackers. Others quickly followed: Bruce Sterling’s anthology Mirrorshades was a genre-defininng collection, while William Gibson’s short stories, including ‘Johnny Mnmonic’ and ‘Burning Chrome’, leading up to his 1984 novel Neuromancer, cemented many of the conventions and tone of the subgenre.

Gibson noted that his specific inspiration came from seeing teenagers playing video games — itself something that could have been pulled out of science fiction just a few years / decades ago — in darkened arcades. “Even in this primitive form, the kids who were playing them were so physically involved; it seemed to me that they wanted to be inside the games, within the notational space of the machine. The real world had disappeared for them.”

That continued into the 1990s and 2000s with books like Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash, Pat Cadigan’s Synners, Richard K. Morgan’s Altered Carbon (ahem), Ian McDonald’s River of Gods, and charitably, Ernie Cline’s Ready Player One.

Notably, cyberpunk and its conventions weren’t limited to just print works. Outside of Gibson’s Neuromancer, Ridley Scott’s film Blade Runner is probably the best example of the atmosphere that cyberpunk cultivated: grim, polluted cityscapes, populated by machines and greedy corporations, all accompanying a cynical mystery. But there was also Tron, Disney’s take on what a cybernetic world might look like, and Robocop, about a wounded police officer transformed into a powerful robot by way of an authoritarian company.

Hollywood has always lagged a bit behind print science fiction, and the 1990s featured a bumper crop of cyperpunk films: 1992’s Lawnmower Man, 1995’s Johnny Mnemonic, (based on a Gibson story) and Ghost in the Shell, and 1999’s The Thirteenth Floor and The Matrix. There have been plenty of video games that play with the genre’s tropes, and there’s certainly a music (check out the band GUNSHIP) cosplay and even lifestyle aesthetic that informs everything from clothing to architecture.

At its core, cyberpunk emerged from the convergence of a global economy and changing technological tides, with its authors often cranking the knob to turn what they were seeing in the 1980s as a worst case future scenario. This wasn’t the rosy, optimistic vision of the future: it was an effort to point out the problematic path we were headed down.

As a result of that origin, cyberpunk often feels like it’s stuck in the 1980s — at least the commonly-held vision of it. The trailers for Cyberpunk 2077 certainly look like they’re pulled right from a 40-year-old fever dream, complete with the neon, cybernetic implants and urban underworld. Certainly, there are more recent works like Altered Carbon, Eli K. P. William’s Cash Crash Jubilee, or Chris Kluwe’s Otaku, all of which really lean into that gritty styling for inspiration.

The 1980s are far behind us — taking with it New Wave and its overdose of chrome and neon. (Note to self: Overdose of Neon is definitely the title of a cyberpunk tribute anthology). While science fiction has moved on a bit, the simmering anger and resentment that cyberpunk always felt like it carried with it didn’t really go anywhere, like that one kid goth kid from high school that never outgrew their attire.

Certainly, the elements of that helped inform the creation of cyberpunk haven’t gone anywhere: the biggest corporations out there now make the companies of the 1980s look small indeed, while the gap between rich and poor has grown ever larger. And of course, we’ve seen our share of technological advances — cyberpunk has nothing on the iPhone. Our cyberpunk aesthetic has transformed into something that’s best characterized by steel, glass and minimalist design.

There are other works that are playing with the pieces that cyberpunk built itself on. One story that comes to mind that feels most like a natural successor to this broader cultural movement (without feeling like it’s a carbon copy) is Neill Blomkamp’s 2013 film Elysium, which follows a felon who has to break into an exclusive space station after he gets a fatal dose of radiation while working in a factory. The discrepancies between the wealthy inhabitants of the Elysium station and the people who’re living down on an overcrowded, dirty Earth highlights exactly what cyberpunk was about, and featured plenty of body-augments, greedy corporate agents, and even some swords.

Another that’s worth checking out is Yilin Wang’s short story “Sparrow,” published a couple of years ago in Clarkesworld — it’s a story that feels like it’s just a couple of minutes away, but which deals with the confluence of technology and its impact on labor.

The genre’s DNA has mutated and percolated out through countless other works too, showing up in everything from Linda Nagata’s high-tech military SF series The Red, James S.A. Corey’s space opera The Expanse, Kim Stanley Robinson’s New York 2140, and P.W. Singer and August Cole’s Burn-In.

As we move into the 2020s, our lives dominated by the likes of online social media, digital entertainment platforms, and hand-held and wearable technologies, we’re certainly living in a mirror version of what the original cyberpunks envisioned for the future. It’s a movement that’s well worth looking back on, even if the neon bulbs have been swapped out for LEDs.

As always, thanks for reading. This week has been a stressful one — I’ve got a big piece going up on Monday, one that’s taken a lot of reporting, time and energy to write up, and I’m eager and nervous to see it out there. I’m going to go unplug for the rest of the night, but check back tomorrow — I’ve got a roundup coming.

Lemme know if you’re playing the game at all — I’d be interested in hearing what other people think.

Andrew