Dragonlance changed how we read fantasy

The franchise's original creators have sued Wizards of the Coast for breach of contract over a new book trilogy

If you went to a bookstore’s science fiction and fantasy section starting in the mid-1980s, you’d likely encounter a block of novels taking up an entire shelf or two: Dragonlance. Originally created by game designer Tracy Hickman and co-written by Margaret Weis for TSR’s Dungeons & Dragons, the Dragonlance novels were part of a much larger multimedia franchise that accompanied hundreds of short stories and modules that supported the game itself.

The book series was a popular segment of fantasy literature through the 1990s, an outgrowth of the popularity of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings in the 1970s, and the authors that followed like Terry Brooks, Glen Cook, Robin Hobb, Robert Jordan, Mercedes Lackey, George R.R. Martin, and Michael A. Stackpole. But while stories like Wheel of Time and Game of Thrones have reached household recognition, Dragonlance has always felt like one of those franchises that’s been quietly influential for millions of fantasy readers, while at the same time was studiously ignored by the more established fandom for the genre.

Despite that, the series changed how fans, readers, and writers alike experience, interpret, and create fantasy literature, and why word of a revival of the franchise would have been big news. Earlier this week, Wired reporter Cecilia D’Anastasio reported that Hickman and Weis have filed a lawsuit against Wizards of the Coast for breach of contract after the company reportedly tanked an in-progress trilogy of novels that would have been their triumphant return to the franchise after being away from it for more than a decade.

The move begs a look into the story of how Dragonlance came to be, what its impact was on the world of fantasy literature, and the nature of franchise writing that the series helped pioneer.

Shared Universe

These days, it’s not uncommon to see a sprawling multimedia franchise — a massive storyworld that’s told across novels, short stories, comics, television shows, video games, and movies. The media world of the 1980s was a far simpler environment.

To fully understand where Dragonlance came from, you have to look further back in time: to the 1970s, when a company called Tactical Studies Rules Inc. (TSR) released a fantasy roleplaying game called Dungeons & Dragons.

In the mid-1970s, two dedicated war gaming fans, Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, decided to give their individual soldiers in their larger, anonymous armies their own personalities and agency. They wanted to create their own characters within those larger stories, and decided to give them a new level of mobility, guiding their characters with a set of overarching rules and the randomness of dice rolls.

The game was an outgrowth of a series of gaming sessions that Gygax and his friends were throwing at the time. They assembled as a group called the International Federation of Wargamers, holding events that eventually became the behemoth known as GenCon, a major convention for gamers of all stripes. From that environment, Gygax and another friend, Don Kaye pooled their money together to form TSR Inc. to sell that first edition of Dungeons & Dragons. With just a couple of thousand dollars, they printed up a thousand copies in 1974, and began mailing them out to buyers.

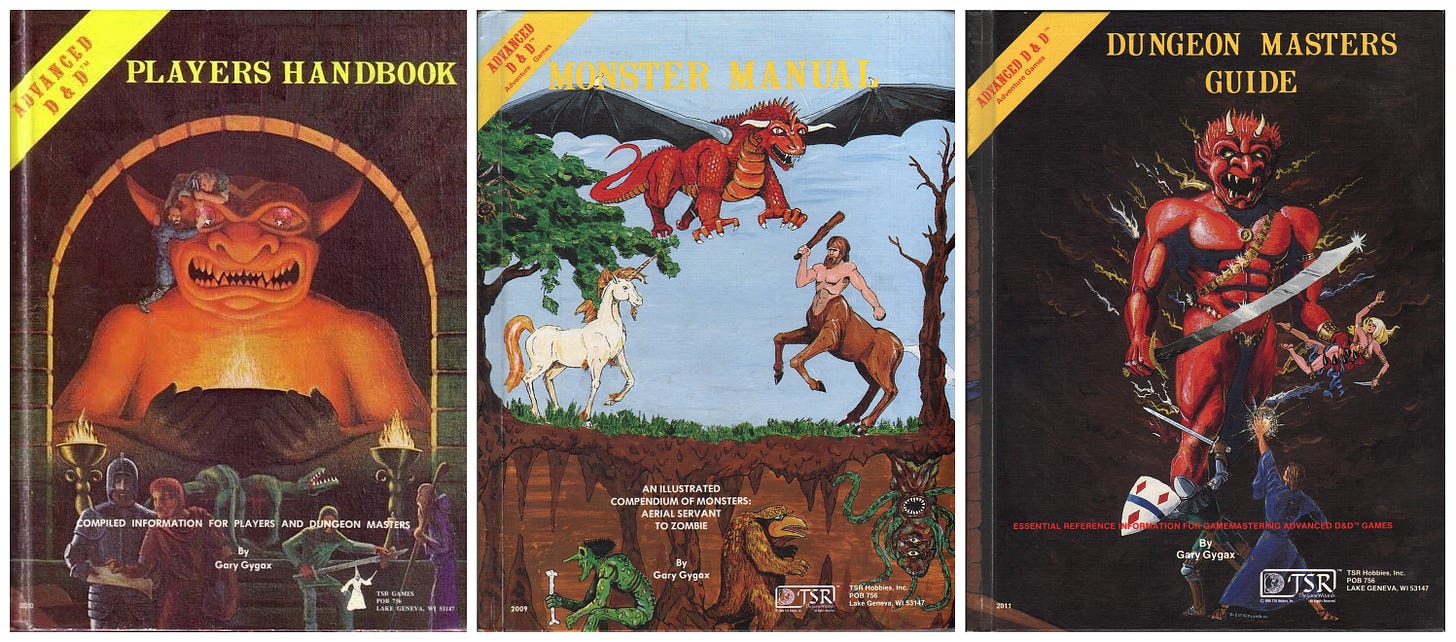

The game proved to be a slow-burn success amongst the gaming community, one that steadily grew with time. In 1977, TSR released a new set of rules for a second edition of the game, as well as a new rulebook: Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, which codified the game’s rules into a single volume for players, along with the Monster Manual and Dungeon Master's Guide. That new edition helped propel D&D into newfound popularity with gamers and the public at large. TSR encouraged players to stretch their imaginations to the limit, building new characters and scenarios to go on new adventures.

As the company matured and gained mainstream appeal at the end of the 1970s, TSR found that it could appease the growing demand for more material by releasing an avalanche of supporting materials: one-shot adventures, campaigns and modules, which featured additional tools for players, like maps and background materials for various settings and scenarios.

The company was expanding into other things as well. According to Michael Witwer, Kyle Newman, and Jon Peterson in their exhaustive art history of the franchise, Arts & Arcana: A Visual History, the mounting demand for licenses “led TSR to create a stable of iconic characters to grace these D&D products.” But financial troubles were brewing: momentum for the game system was stalling, and TSR needed to find new sources of revenue to stay afloat. Witwer notes that those mounting financial pressures prompted it to “produce new, innovative, and best-selling products such as the newly released Companion Set.”

Around the same time, Tracy Hickman, one of the company’s game designers, had begun to create a set of modules all about dragons: a series of interconnected modules in which players would take on the fearsome beasts, something that wasn’t entirely common, despite the game’s namesake.

Hickman, Witwer writes, “immediately saw more to it than just packaged adventures: it would include books, calendars, wargames, miniatures, and even a novelization of the series, augmented by short stories in Dragon magazine.” TSR liked the idea, and commissioned one of its artists to design some concept art. The result was the start of a major initiative. “Hickman was now tasked with guiding a team of designers to develop his concept for the first trilogy of modules in this radical new multimedia venture…It was the most complex rollout that TSR had ever undertaking for a single campaign — a risky but potentially lucrative endeavor.”

TSR wanted more than just a game: they recognized that people if players liked playing out the adventures, they might also enjoy reading them — and that novels set in the world might be a good pipeline for new gamers.

One of the people that TSR brought on to help with the project was Margaret Weis, who had joined the company in 1983. Her first task was to edit this large project, code-named Project Overlord. Profiled in Dragon magazine in 1998, she recalled that she and Hickman had plotted out the novel and hired another writer to write it, “who didn’t work out.” The two of them picked up the project instead. “By that time, Tracy and I were so into the project that we felt we had to write it.”

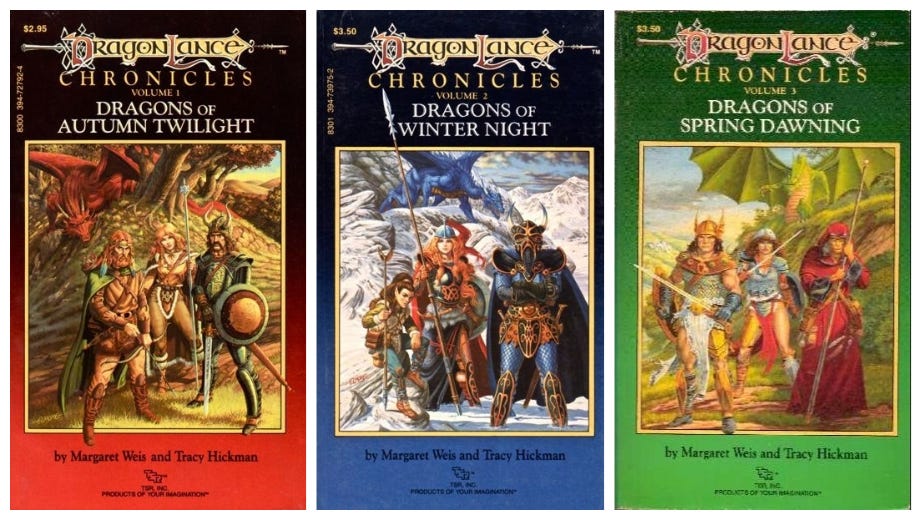

The first installment of that trilogy, Dragons of Autumn Twilight, hit stores in November 1984: which was quickly followed by Dragons of Winter Night and Dragons of Spring Dawning the following year. The trilogy accompanied a lengthy series of adventures that TSR released, all of which were set in the world of Krynn.

The series is a massive amalgamation of fantasy tropes that shares the same setting, one largely informed by J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. The books followed a series of adventurers who reunite after being away for five years of questing. The world is experiencing some turmoil as a new order has risen up to worship a new set of gods, and who have aligned themselves with the Dragon Highlords, with the intention of taking over their home. There’s fights, questing, ancient artifacts, and more, all elements of a good campaign.

The publishing program was a success for TSR: the first novel hit bestseller lists, and Witmer says that just a couple of years later, fans snapped up “more than two million copies, pulling in more than a half million module sales as well.” Ultimately, the entire franchise included hundreds of anthologies and novels.

Following the success of Dragonlance, TSR would set up another major franchise/campaign setting a couple of years later: Forgotten Realms. Designer Ed Greenwood had created the setting decades earlier — its earliest origins predated D&D — and he resurrected it for a new line of articles, fiction, and campaign settings in 1987. Like with Dragonlance, TSR began releasing tie-in novels that explored the setting, starting with Darkwalker on Moonshae by Douglas Niles in May 1987. That franchise reached new popularity with R.A. Salvatore’s The Crystal Shard in 1988, introducing a character named Drizzt Do’Urden, which became a fixture in his subsequent novels. Other campaign settings, like Mystara, Ravenloft, Spelljammer, Dark Sun, Planetscape, Eberron, and others would also get their own series of tie-in novels.

Weis and Hickman had their ups and downs with the franchise in the years that followed. They left TSR in 1987 and embarked on their own fantasy projects, publishing their Darksword series with Bantam Books between 1987 and 1997. They returned to Dragonlance in 1995 for Dragons of Summer Flame and in 2006 for the Lost Chronicles trilogy. Ultimately, they wrote more than 30 installment for the franchise.

Dragonlance petered out in the 2000s and 2010s. Wizards of the Coast, which had acquired TSR in 1997, was acquired two years later by Hasbro. In the years that followed, sales of D&D products stagnated, facing competition from video games like World of Warcraft and others. Around the same time, the company pulled the plug on Dragonlance and its publishing contracts with Weis’s publishing company, Sovereign Press, Inc. Dragonlance seemed to be one more casualty of a declining interest in in-person roleplaying games.

But things began to change. In the mid-2010s, a resurgence in interest in Dungeons & Dragons began, driven by high-profile product placements in shows like Stranger Things and Community, and podcasts like Critical Role. And it seemed as though that popularity had prompted Wizards of the Coast to take a close look at revitalizing some of their earlier, beloved brands.

Adventures on the Bookshelf

Dragonlance’s popularity didn’t exist in a vacuum, nor, for that matter, Dungeons & Dragons. The origin point of a literary genre is often a moving target, but the roots of fantasy literature stretch back centuries. The modern origins of fantasy got its start alongside science fiction in the 1920s and 1930s, with authors such as H.P. Lovecraft, Robert E. Howard, C.L. Moore, and others forming the edges of “Sword and Sorcery” fantasy.

And then J.R.R. Tolkien arrived on the scene, publishing The Lord of the Rings in 1954 and 1955, a dense narrative of good verses evil set in an exhaustively detailed world that left a huge impression on readers around the world, especially once it came over to the United States in the 1960s.

With the enormous success of the trilogy, US publishers began to work out how to fill a new hole in the market. According to Aidan Moher, the Hugo Award-winning writer behind the blog A Dribble of Ink, that success wasn’t immediate, and it wasn’t until the 1970s that editor Lester del Rey found a pair of suitable heirs to Tolkien: Terry Brooks and Stephen R. Donaldson. Moher explained to me that the two authors take on different approaches to Tolkien’s structure. Brooks imitated it closely, while Donaldson went for something more subversive, and each finding immense success in the soon-to-be-burgeoning field of epic fantasy.

Brooks, Moher explained, was able to tap into something that new fans of Tolkien really desired: congruency. They wanted more immersive worlds and adventures for bands of heroes to undertake as they strove to push against some sort of evil that was sweeping over the land. Brooks’ debut novel, Sword of Shannara, filled “the Hobbit-shaped hole that I’d never known existed inside of me,” he wrote. “I didn’t want something new. With all the fervor and passion in my adolescent body, I wanted to start over and experience from scratch that same wonder I’d felt while reading Tolkien. I wanted hidden magic, elves, dwarfs, and a whole new fantasy world to explore.”

In many ways, Dungeons & Dragons did exactly the same thing. Gygax and his fellow creators were certainly influenced by Tolkien, and the framework that they created allowed gamers to undertake their own Tolkien-like adventures. The works by Lackey, Jordan, and others did the same for readers.

There were other elements that helped speed along the explosion of fantasy literature: chain bookstores that were popping up around the country. In The Book in Society: An Introduction to Print Culture, Solveig C. Robinson notes that the 1960s and 1970s were a “period of great transition in retailing, with many stores of all kinds abandoning Main Streets and High Streets in favor of the new suburban shopping malls.” Stores like B. Dalton’s, Walden Books, Borders, and Barnes & Noble provided a new level of access to casual readers around the country, and often at much cheaper rates, given that they could buy in bulk. Chain bookstores, notes Moher, also “had lots of space for science fiction and fantasy books,” often in dedicated sections and prominently displayed for customers.

Moreover, both TSR and publishers realized something: their fans were hungry for new content to consume, and that if they could provide a continuous stream of fat new doorstop fantasy titles, their readers would buy them.

This period was enormously beneficial to genre fiction: Frank Herbert’s Children of Dune is anecdotally the first science fiction novel to hit The New York Times Bestseller list, and publishers extended generous contracts to Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov to extend their best-known series with new installments. Fantasy was part of that, and authors like Brooks, Jordan, Lackey, and others found enormous success with their own fantasy worlds and their own lengthy series.

And while individual authors couldn’t turn out a new book returning to that fantasy world every couple of months, a handful of writers could. They didn’t have to be the same quality as that of Tolkien, either. As a result, TSR, along with Hickman and Weis, plotted out an ambitious schedule of Dragonlance novels through the 1980s, tapping the writers who helped to create the world to write up adventures there. “Tie-in novels,” Moher explained, “could easily fill the fans’ demand for more content.”

The result? A mass-produced literary movement that proved to be exceptionally popular with fantasy fans and gamers. Established fans and fandom might have turned its nose up at the books for a variety of reasons — relative levels of quality against “original” works, the use of recycled tropes, formulaic quests, and so forth — but the books were exceptionally popular nonetheless.

That popularity, says Moher, was important to the genre as a whole. “There’s a clear path from this sort of popcorn fantasy into more complicated works.” Fantasy-inclined readers didn’t need to start with the density of Tolkien: they could start with books that were simply easier to read and enjoy.

Dungeons & Dragons, along with Dragonlance and Forgotten Realms, “probably created the most fantasy fans outside of Tolkien” Moher says. That bears out with conversations that I had with friends. My friend and DM Sam mentioned that he read the books alongside the other fantasy that he read in the 1990s.

Man those books were great. Was so excited when Dragons of Summer Flame came out.

— Noah Lee (@Noahbot) October 21, 2020

Another friend, Noah, noted that it was the first fantasy series that he really got into: “I didn’t know anything about D&D or even Lord of the Rings,” he told me via DM. Another friend, Mary, explained that she too came to the series before Tolkien and the genre’s other big names “What attracted me was how true fantasy it felt from the beginning; magic, swords, ranging through big forests, no real technology, different races and tribes and classes of people. It felt completely separate from reality and that was what I loved.”

Others have paid tribute to the series. Jeremy Finley, writing at Tor.com, noted that Dragonlance was his first “foray into fantasy,” Jason Heller pointed out at The AV Club that the games “filled a very real void” for fans who simply wanted a solid comfort read, Lauren Davis at io9 noted that she’d grown up reading them, and Jared Shurin at Pornokisch noted that while they weren’t exactly good reads, they were influential, and left their fingerprints on the works that we’re seeing published today.

Lawsuit

So where does this leave us now? Dungeons & Dragons is enjoying a period of sky-high popularity boosted along with help from the likes of Community, The Big Bang Theory and Stranger Things, but also a widespread attraction to in-person (remember those?) gaming sessions that encourage improvised storytelling and creativity, as well as the advent of game streaming through platforms like Twitch or YouTube.

As a gaming system, the game has its appeal for nostalgia for the 1980s, but with its own particular stable of characters, stories, and world, Hasbro and Wizards of the Coast have a valuable set of properties that it can then leverage into new mediums, like television or films. Indeed, there’s a new Dungeons & Dragons movie in the works, and as well as other projects that’ll draw on the underlying foundation.

So it makes a certain amount of sense that Wizards would want to revive the Dragonlance property: it’s more content to engage the established fanbase with. According to the suit, Weis and Hickman learned that Wizards of the Coast were “receptive to licensing its properties with established authors to revitalize the Dungeons & Dragons brand” in 2017, and they reached out to gauge the company’s interest with a new book trilogy.

“[Hickman and Weis] viewed the new trilogy as the capstone to their life’s work and as an offering to their multitude of fans who had clamored for a continuation of the series.”

As of 2019, they began negotiations for a licensing agreement with Wizards, and soon, they had a deal. This gets a little complicated, because there are several parties involved. Hickman and Weis would write the story, Wizards of the Coast would have editorial control and sign off on it, and Penguin Random House would publish it.

Hickman and Weis then went out and wrote the book, and Penguin Random House appears to have signed off on its end. The contract that they signed will spell out what both parties are responsible for — they’ll have to hit a certain word count, turn it in by a certain point in time, address edits in a timely manner, and so forth. In their lawsuit, Hickman and Weis say that they “met all contractual milestones and received all requisite approvals from [Wizards of the Coast].” In June, Wizards brought in a new pair of editors to oversee the project: Nic Kelman, the company’s Director of Entertainment Development, and Paul Morrissey, Wizards’ publishing lead.

Things appear to get a bit sticky after that point. Some of those edits appear to have concerned issues of race and gender. The lawsuit notes that the new editorial team issued a set of comments concerning the project: addressing “the use of love potions in the story, as referenced in the 5E Dungeons Masters Guide, to concerns of sexism, inclusivity and potential negative connotations of certain character names.

“[Wizards of the Coast] proposed certain changes in keeping with the modern-day zeitgeist of a more inclusive and diverse story-world,” their lawsuit states, and that “at each step [Hickman and Weis] timely accommodated such requests, and all others, within the framework of their novels.”

But in August, Wizards of the Coast got everyone on the phone with their lawyers, and said that they’re not going to approve any further drafts of the project. This is the point where Weis and Hickman say that Wizards has breached its obligations: they already accepted the book, and argue there aren’t other mechanisms in the contract where the company can justifiably stop the project. It’s accepted, they argue, and you can’t take that back.

They want damages: they’ve spent three years working on the project, something that they’re not able to now publish. They’re seeking 30 million in damages from lost income, a juried trial, and for the court to essentially order Wizards to approve the manuscript for publication (or provide more edits).

But while a number of fans have taken to comment sections and Twitter to excoriate Wizards for their conduct, it’s worth pointing out that within the legal system, this is just Weis and Hickman’s side of the story. According to one legal expert I spoke with, the case seems like a fairly open and shut breach of contract case, and “if you want to get Dungeons & Dragons about this, this is just a plea to a sovereign.” The company will now have to respond to the lawsuit in some form, either with a brief of its own, or with a settlement to the authors.

And without seeing the original licensing agreement at the heart of this, it’s impossible to know what avenues Wizards of the Coast might have to terminate the project. Nor have they said why — through a representative, Wizards of the Coast declined to comment, saying that it doesn’t speak about pending litigation. Margaret Weis and Penguin Random House didn’t get back to me by the time I sent this out.

It’s entirely possible that the company does have a solid reason for dropping it, and there’s a clause in the contract that serves as a sort of trap door: something that the company’s legal department can use to kill the project. But until we hear more from them, we won’t know for sure.

This brings me to another point. Clearly, something has prompted Wizards to abruptly halt work on the project, and it seems as though it has something to do with the edits that the various parties were going back and forth on. The lawsuit specifically pulls out the sensitivity edits as something that they adhered to, and taken on its own, it seems like a strange thing to highlight — why not just say “edits?”

In the lawsuit, Weis and Hickman point out that Wizards and its various products have had its share of PR and sensitivity problems as well, issues that have become more visible for the company in the aftermath of the killings of Black men and women such as George Floyd and Brianna Taylor and the protests that followed. Those killings led to widespread protests across the United States and the rest of the world, and has led to a reckoning over inclusivity within a number of industries — publishing included.

As a product of the 1970s and 1980s… Dungeons & Dragons and other products like Magic: The Gathering don’t really score all that well in that regard. Polygon’s Susana Polo and Charlie Hall wrote up an overview of how the gaming industry was grappling with this, and it includes examples of how Hasbro removing some Magic cards because of their racist imagery, and that it was adjusting some D&D elements to remove racist portrayals.

Throughout the 50-year history of D&D, some of the peoples in the game—orcs and drow being two of the prime examples—have been characterized as monstrous and evil, using descriptions that are painfully reminiscent of how real-world ethnic groups have been and continue to be denigrated. That’s just not right, and it’s not something we believe in.

The lawsuit also points to a couple of other PR issues: criticisms of Kelman over troubling content his 2004 book, girls: A Paean, as well as the company’s prior relationship with Terese Nielsen, an artist who’s allegedly sympathetic of Qanon (through donations to a conspiracy theory YouTube channel).

This seems as though it’s painting a contradictory picture of Wizards: that there’s a longstanding history of insensitive content (fair), but at the same time, that the additional sensitivity edits were a thing potential stumbling block that put the brakes on the project. The requested changes that the team put forward seem to be good observations around issues of consent, racial identity, and sexism, and that Weis and Hickman had to conduct some extensive rewrites — 70 pages worth. These actions doesn’t strike me as actions that a company would take if they’re indifferent to these issues.

Read one way, Wizards might have found that they had a book that they couldn’t sell without generating additional controversy, and opted to cut their losses and go in a different direction. Maybe it’s the result of some internal restructuring, with the new overseers and Weis and Hickman simply not seeing eye to eye on the final vision of the project. Maybe they wanted to concentrate their efforts on a new line of IP that doesn’t have the baggage and lore that stretches back 30 years. Or, as what Weis and Hickman think: Wizards simply wanted to deflect from the negative attention that it got earlier this year by killing off the project.

I don’t really see the logic behind that. The company certainly isn’t pulling D&D or Magic: The Gathering from the market: indeed, Kelman’s job (according to his Linkedin profile) is to produce a MTG TV series, develop the company’s properties for TV, and direct an in-house publishing group to commission, edit, and publish books about those properties. So, I can’t help but think that either there’s something wrong with the book that Wizards just isn’t willing to put the effort into resuscitating, or that there was some personality thing where people didn’t see eye to eye on the end result.

Regardless of the underlying reason, or the outcome, the entire situation feels like an unfortunate end to the entire body of lore that TSR started back in the 1980s.

TSR’s approach the story itself was incredibly influential. A handful of years later, Lucasfilm took on a similar approach with the Star Wars franchise — using its existing catalog of roleplaying games to support the world that Timothy Zahn recreated for his 1991 novel Heir to the Empire, which blossomed into its own story universe, one that stretched far beyond the original films, branching into a constellation of video games, comic books, new films, and eventually, TV shows.

Ultimately, TSR helped usher in a new style of storytelling: a multi-medium platform that featured the collaborative efforts of hundreds of writers, editors, artists, and storytellers, guiding readers and players through a massive series of shared adventures. At its core, this framework helped to reinforce a product line and franchise in a self-sustaining ecosystem, keeping fans engaged with the company’s products, stories, and world.

As fantasy literature, the prose might have left something to be desired, it might have been entirely familiar and clichéd for traditional fans, but Dragonlance was an influential story world that introduced fantasy to an entire generation of fans, and which undoubtably inspired some of them to pick up a pen themselves and begin telling their own stories. It led to the rise of new characters and stories that readers fell in love with, and encouraged them to move onto other works, within the Dragonlance framework, or beyond.