Endless Universes and Tales of Two Worlds

Hello!

It’s been a weird week, hasn’t it? I spent the weekend getting away from home for a couple of days by visiting my parents in upstate New York. (Fortunately, Vermont has relaxed some travel restrictions, allowing us to go out to low-impact counties and return without having to self-quarantine.) It was relaxing when I could get away from the internet and I’ve gotten a bit of reading done while I was out there. But I’ve been glued to the news, and I’ve found it hard to keep focused on … pretty much anything else.

This issue: I have some thoughts on some news about the upcoming season of The Mandalorian, and what that could mean for the future of Star Wars, as well as a review of Hao Jingfang’s new novel Vagabonds.

Next Paid Issue

Since I’ve turned on subscriptions, a number of you have signed up. Thank you so much — I’m excited at what’s to come for this project. The next issue of this newsletter will be released to paid subscribers (as noted before, free issues will still continue.)

This next issue will be about the recent fracas that J.K. Rowling has created for herself, as well as another that hasn’t gotten as much attention: Richard K. Morgan. Their stances are pretty terrible, and are at stark odds with the worlds they created.

In another upcoming issue, I’ll be taking a look at the legacy of Michael Crichton’s body of work, and what the future might hold. Stay tuned!

The Mandalorian Isn’t a Standalone Series

The last couple of months have brought a couple of interesting bits of news for the Star Wars franchise. Temuera Morrison and Katee Sackhoff have each reportedly been cast in the upcoming season of The Mandalorian. Morrison will be playing Boba Fett (and maybe Captain Rex), while Sackhoff will be reprising her role as Bo-Katan. Couple that with the news that Rosario Dawson might be playing the live-action version of Ahsoka Tano, and you have a whole bunch of characters from the animated shows migrating over into the live-action franchise. There are also rumors that Disney is looking for someone to play a live-action version of Thrawn, possibly for his own series. (Take that last bit with a grain of salt.)

What does this mean? Well for one, it highlights that shows like The Clone Wars, Rebels, and The Mandalorian — as well as the standalone projects like Rogue One and Solo (and presumably the upcoming shows about Obi-Wan and Cassian Andor) — aren’t distinct entities, but are rather installments in a much larger story.

When Disney purchased Lucasfilm in 2012, it didn’t just buy six films: it bought a massive trove of IP and a databank of characters, all of whom could be utilized in future movies and television projects. From there, it can build up a self-reinforcing franchise that hits consumer eyeballs in every conceivable way: in theaters, on home televisions, books, comics, video games, audio dramas and so forth. (We haven’t seen a narrative Star Wars podcast like Marvel’s Wolverine: The Lost Trail, but I wouldn’t be surprised if we see one at some point. Lucasfilm, call me.) As such, we’re starting to see this blend of characters: Ahsoka and Rex, who popped up in Rebels and now Mandalorian, show that the events of one project can lead into another.

I’ve been seeing and hearing rumors that Ahsoka, Captain Rex, and Bo-Katan (and maybe others?) are only set to appear in a limited fashion in this particular season, but that their appearance could be a backdoor into a series of their own, one that continues the ongoing storylines that we saw in Clone Wars and Rebels.

On one hand, this is pretty cool to see, and I wonder if we’ll see Disney build out this post-Return of the Jedi franchise starting with The Mandalorian into something bigger, much like creator Jon Favreau did with Iron Man a decade ago (which eventually became the MCU). We know that Disney is talking about spin-off shows for The Mandalorian, and I have a hunch that what we’ll see is a handful of Star Wars shows that all intersect in interesting ways, much like Marvel did with its Netflix franchise. Within that timeframe, what will Star Wars look like a decade from now? Multiple shows / films building to a massive conclusion? It’s certainly not going anywhere.

But on the other hand, there’s a certain fatigue that’s definitely going to set in. Stories, I feel, need to have concrete arcs and endings: there needs to be a point to the story itself, rather than a continual stream of adventures. The MCU’s model sort of worked here: mini-arcs with individual characters that sort of did their own thing until they were brought together. But I skipped a bunch of the Marvel films, and found that most of them just felt like they were always setting up for the next adventure.

“All his life has he looked away... to the future, to the horizon. Never his mind on where he was... what he was doing.”

Yoda had a good point here: if you’re always setting up the next thing, you’re not really focusing on the here and now. That’s one reason why I think The Last Jedi really resonated: it wasn’t focused on the past or future of Star Wars — it was deconstructing the tropes that make it up in order to make some really interesting points.

Hopefully, Lucasfilm and Disney will be mindful of franchise fatigue when it comes to Star Wars, and that we’ll be seeing these characters for more than just setup for the next big thing.

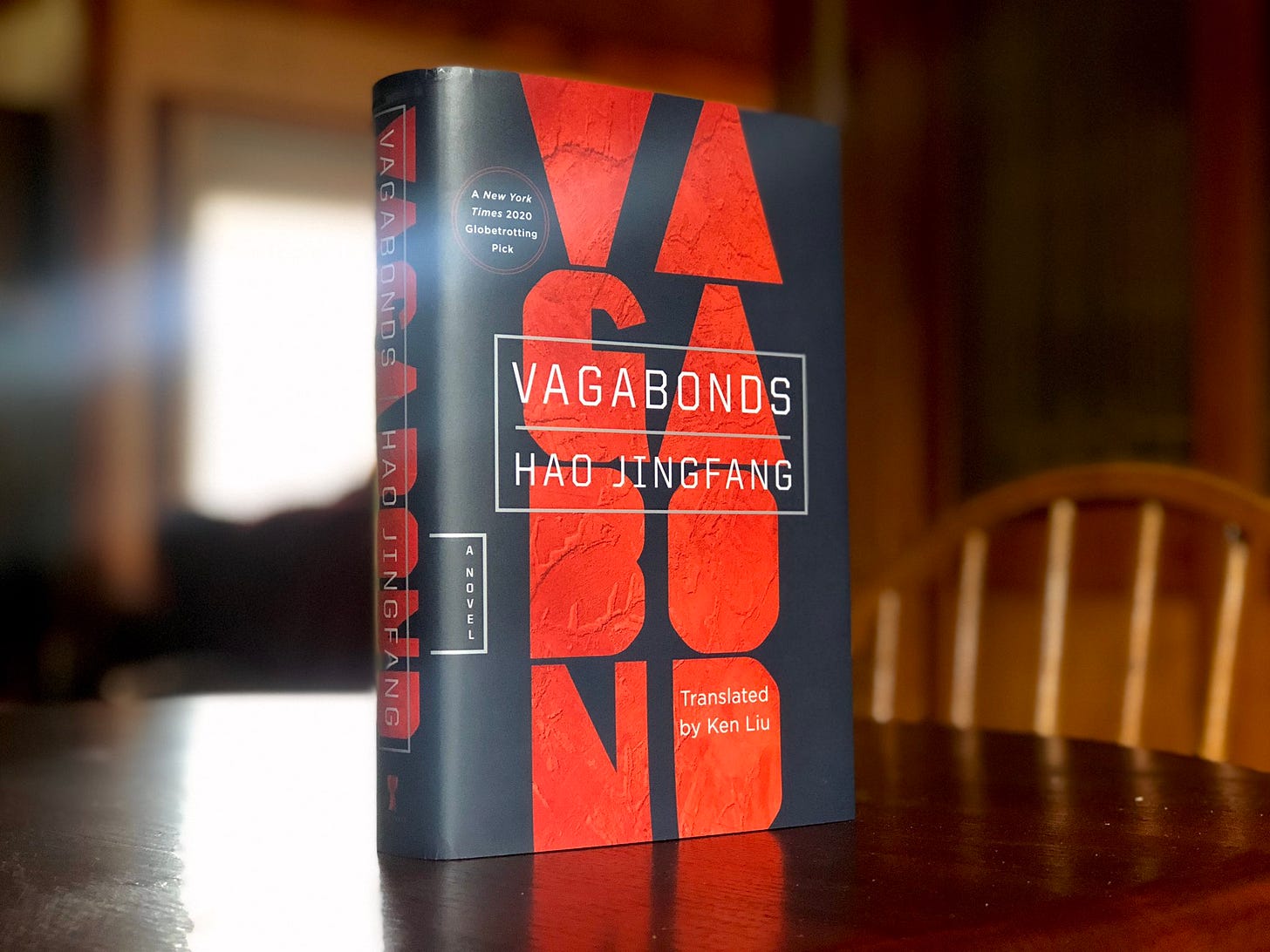

A tale of two worlds: Hao Jingfang’s Vagabonds

Science fiction is a genre that’s fascinated with the implications of colonization: take a seedpod of people (in the form of a generation or colonial ship), and transplant them in a new place, allowing a new society to grow in new, fertile ground. Sometimes, authors use the opportunity to look at how to build a better world that sheds the problems that they’ve left behind. In other stories, we see two societies juxtaposed against one another, to see how fiction presents itself between the two mindsets and ideologies.

That’s the case with Hao Jingfang’s novel Vagabonds, which Ken Liu translated into English earlier this year. Set centuries in the future, humanity began to colonize Mars, only to launch a revolution that severed ties from Earth. In the decades that followed, the two worlds established vastly different civilizations: Earth continued on a trajectory of hyper-capitalism based on the market for intellectual properties, while the new Martians build out a society built on collectivism and equality. As the embers of war cooled on each side, the two began to reach out to reestablish ties and to get trade up and running once again.

To that end, Mars dispatched a group of young Martian students in 2196 — known as the Mercury Group — to live on Earth for a period of five years. They integrated into life on Earth, and then returned home. What they found when they returned was disillusionment: their homeworld was not as idyllic or equal as they’d remembered, and as they question their surroundings, they find that they really don’t fit in anywhere.

Along the way, one of the Mercury Group members, Luoying, (the granddaughter of a prominent Martian leader), begins to question her participation in the expedition, and as she does so, begins to learn more about her family’s history, and how it’s rooted in the war that separated the two planets in the first place.

Chinese science fiction is a field that’s growing here in the US, based in part on the success of Cixin Liu’s Three-Body Problem and the work of places like Clarkesworld Magazine. Given the economic and technological rise that China’s experienced in the last decade or so, it’s not a surprise that the genre has grown, bringing with it a number of new voices that have joined the ongoing global conversation that is science fiction. Other authors out there include authors like Chen Quifan (Waste Tide) and Xia Jia (A Summer Beyond Your Reach), but as Liu has told me, trying to distill Chinese SF into a couple of common tropes or themes is difficult: every author brings something different to the genre.

Despite that, the stories that I’ve read from China are commenting on the state of the world to some extent — as any science fiction story does. Jingfang has been acclaimed for commenting on the inequality in her home country with stories like “Folding Beijing”, and Vagabonds takes some of these ideas onto a greater stage.

The central idea here is the conflict between the two, diametrically opposed worldviews, and it’s hard to read this story as anything other than a look at the differences between the US and China: one where the ideals of the free market are prized, and another where a sort of collectivism is championed.

However, Jingfang talks a fine line between both. Her Martian students had to work to adapt to life on Earth as they tried to come to terms with how people went about their lives, trying to profit off of their skills and talents. But back on Earth, they find issues with how Martian society is set up: people have guaranteed income and housing, as well as placement in professional guilds known as “ateliers”, but they can’t choose where they go or do, and efforts to change the system are met with resistance and punishment.

Vagabonds is a slow but rewarding read, and it’s one that examines an issue that I see everywhere these days: how do groups of people, systems, or organizations pass along information, history, and habits from one person to another? It’s a novel that examines the systems (in all their forms) around us, and presents an argument that meaningful change is possible, but difficult. Jingfang puts forth an argument that in order to understand the present, we have to understand the complicated route that the past took to get to this point, something that’s appealing to me as a historian.

What Jingfang (and Liu) has written is an engrossing philosophical musing that stands up to some of the best that the genre has to offer: a sprawling novel that explores the state of the world as it stands to day, with some pointed thoughts on how today could turn into tomorrow.

Currently Reading

I’ve finished a handful of books on my to-read list since my last newsletter. I blew through N.K. Jemisin’s The City We Became, which I absolutely loved: stay tuned for some thoughts on that in the nearish future.

I also picked up Daniel H. Wilson’s The Andromeda Evolution, which I’d started last fall and set aside. That was another quick read, which I enjoyed, although Wilson cranks the dial up from “standard techno-thriller” to “holy shit, he did what?”. I’ll have some more in-depth thoughts about this book in an upcoming paid letter.

Finally, I also finished P.W. Singer and August Cole’s latest thriller, Burn-In, which I really enjoyed: that one’s a near-future look at what robotics might look like in a couple of decades. Highly recommend this one if you’re interested in the technology side of media / fiction.

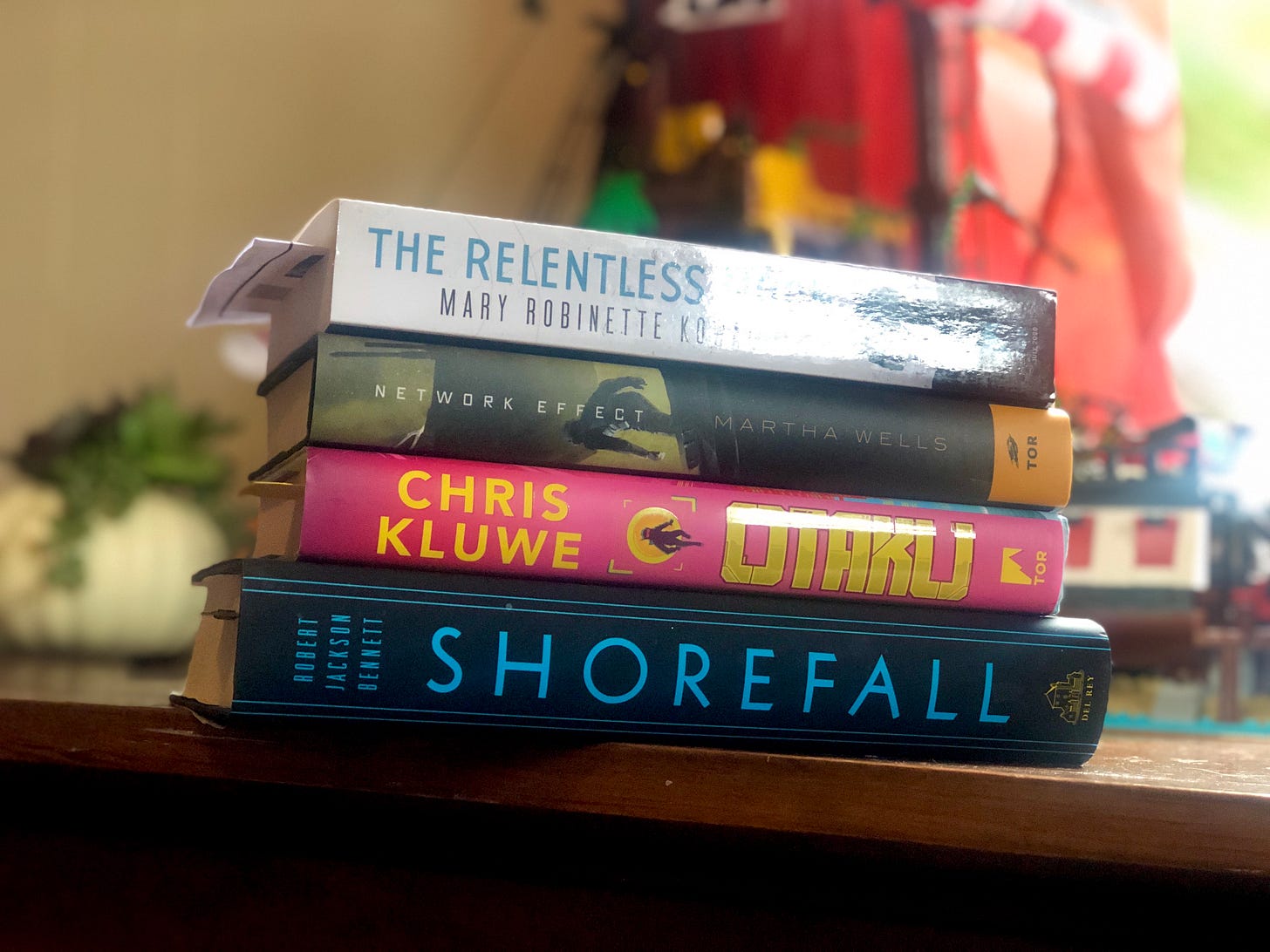

On the current to-read list? I’m listening / reading to Robert Jackson Bennett’s Shorefall, which I’m really enjoying, working through Frank Herbert’s Dune still, and I recently picked Chris Kluwe’s Otaku again. On tap? Network Effect by Martha Wells, and Mary Robinette Kowal’s The Relentless Moon, which comes out next month. Plus some others.

Further Reading

- Audible’s Exclusive Audio. Bloomberg has an interesting article up about how Audible is pushing into more exclusive audio content: podcasts. The company has been releasing Audible Originals for a while, but it looks like they’re ramping up that effort by spending a lot of money to snap up creators and projects to help lock people into their platform.

- Finna Review. I placed a review of Nino Cipri’s latest novella Finna over with my local alt-weekly paper, Seven Days. When it comes to book reviews, they only publish pieces about local authors, and I was really intrigued to learn that Nino is a Vermont native and resident. It’s a fun little book that looks at the horrors of dimensional portals and box-store capitalism.

- Nebula Awards. SFWA announced this year’s Nebula Awards, and I was completely surprised by the winners. My money for best novel was Gideon the Ninth or The Ten Thousand Doors of January, but Sarah Pinsker’s A Song for a New Day took the top prize. Solid list this year — it’ll be interesting to see how the Hugos turn out.

- New York Times Bestsellers. This is a fascinating analysis: someone crunched the demographic numbers of the NYT’s bestseller lists, and came away with some unfortunate findings: nearly 70% of those authors are white, black and east Asian authors only make up 9% of the list, while everyone else comes in at 2-3%. Not a great look, and a good argument for continual reexamination of one’s coverage / choices. Not just for the NYT, but for publishing and the entire sphere in general — including this newsletter. I’m constantly trying to improve and read more widely, to varying degrees of success.

- Science Fiction Places. In this neat article in Places, William O. Gardner argues that science fiction and architecture in Japan are inseparable.

- Solitude of Edward Hopper. The New Yorker takes a look at the art of Edward Hopper (one of my favorite artists) in the context of the lockdowns.

- Uncle Hugo’s Science Fiction. During the riots in Minneapolis, a long-standing fixture of the community, Uncle Hugo’s Science Fiction Bookstore, burned down. The owner is working to rebuild, and I wrote about their plight for Tor.com. Consider donating to the store if you have the means. I just kicked two boxes of new books out to them to help resupply their inventory.

That’s all for this week. As noted earlier, the next issue will be one for paid subscribers, and it’ll be a look at some of the problematic stuff J.K. Rowling and Richard K. Morgan have been saying. In the pipeline, I’ve got a review of The City We Became that I’m musing, and some other things as well.

As always, thank you so much for reading. Let me know what you think — either in the comments or via email, and let me know what you’ve been reading.

Andrew