Expanding the Crichtonverse

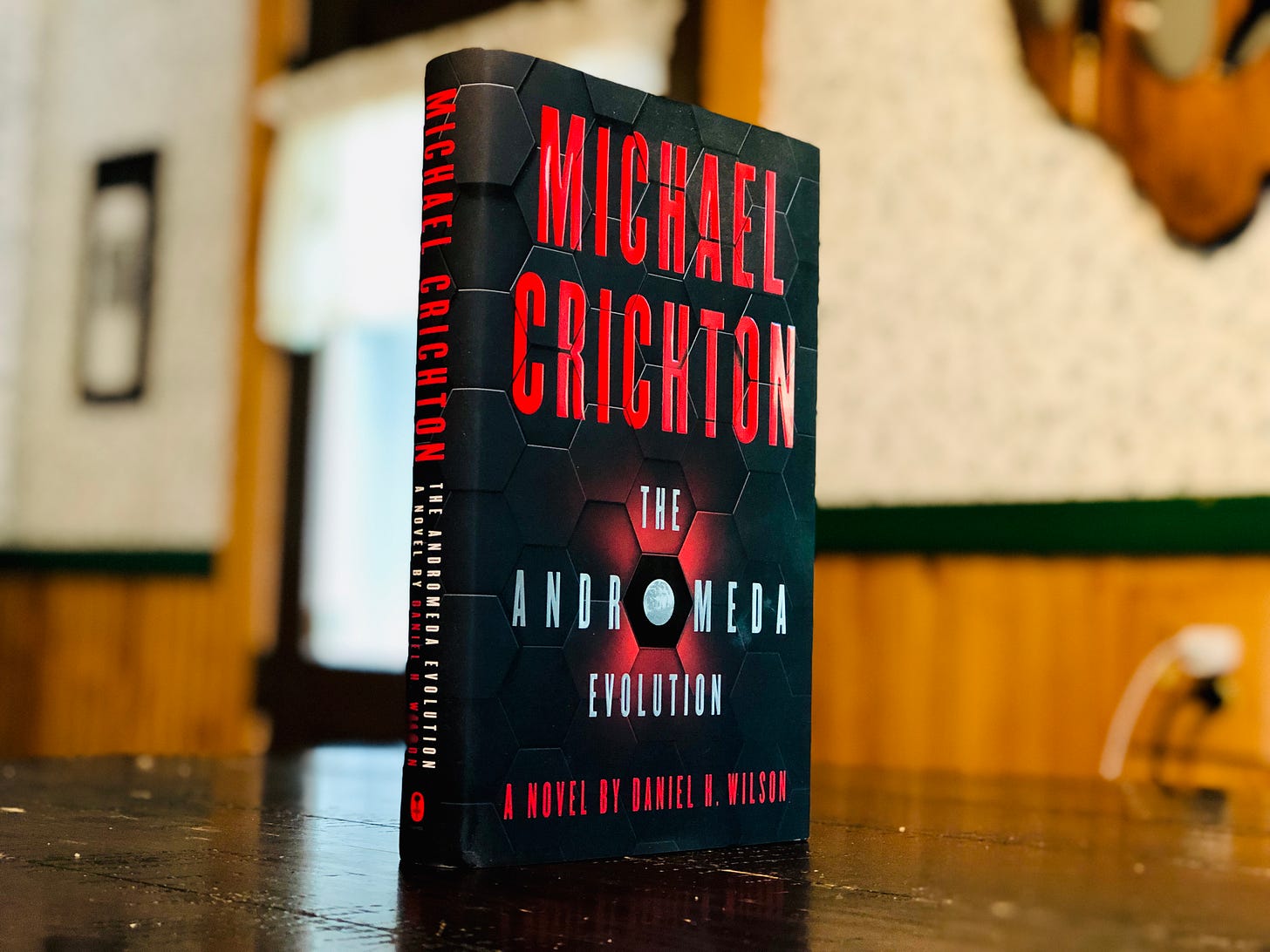

In November 2019, a familiar name appeared in bookstores: Michael Crichton. Crichton had died at the age of 66 in 2008 after a brief battle against lymphoma, but there his name was emblazoned in red on the cover of a new novel called The Andromeda Evolution. The book in question wasn’t written by the late author, however: it a collaboration between his estate and Robopocalypse author Daniel H. Wilson, an original story that built on one of his best-known novels.

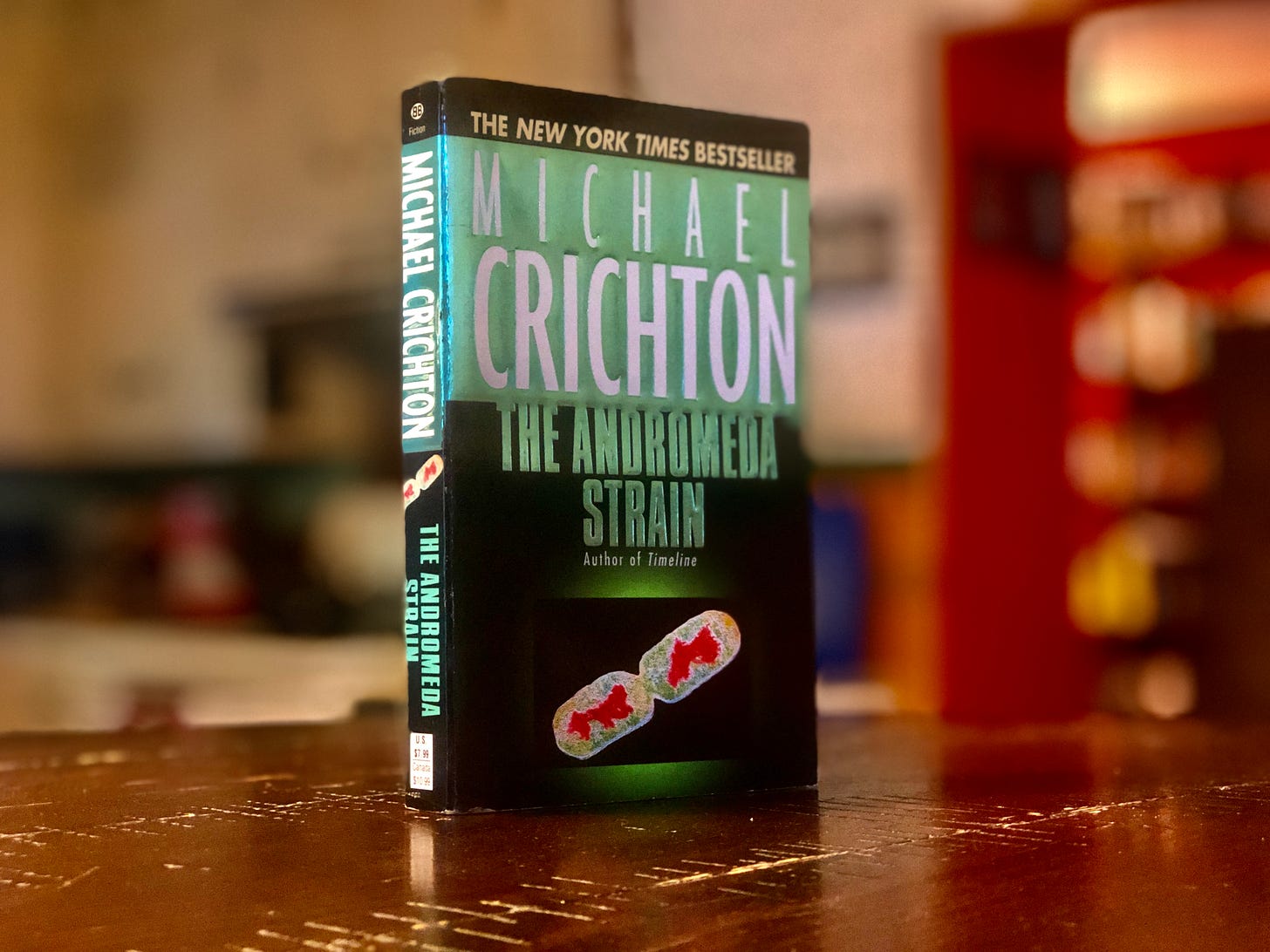

The novel is a sequel to Crichton’s 1969 novel The Andromeda Strain, a book that catapulted him onto bestseller lists and made his name synonymous with the phrase “techno thriller.” This new novel picks up the story fifty years after it supposedly took place, and runs with it, building on the concepts and catapulting them into a new, lofty direction.

Over course of his career, Crichton introduced readers to a wide range of cutting-edge concepts, from cybernetics, to resurrected dinosaurs, to plausible takes on time travel, creating a lucrative body of work that is now a proverbial gold mine in today’s entertainment world. Wilson’s book can be looked at in two ways: a way to capitalize on the IP that the late author created, or to introduce his body of work to a new generation of readers by building on his legacy. The truth is probably somewhere in the middle.

The Andromeda Strain

At the top of his game, Crichton turned out remarkable techno thrillers, setting up a new genre of science fiction that entranced mainstream readers. They blended together the latest scientific concepts with a sense of paranoia about how those technologies could be misused, along with a smart hero that saves the day that you could root for. Absent his work, other techno-thriller authors like Daniel Brown, Blake Tom Clancy, Crouch, Clive Cussler, Daniel Suarez, or Andy Weir probably wouldn’t have had the successes that they’ve enjoyed over the course of their respective careers.

All of that goes back to The Andromeda Strain. While it was the first to come out under his own name, Crichton had already established a career as a novelist, publishing a number of medical and crime thrillers under a couple of other pen names while studying medicine at Harvard Medical College: as John Lange, he published Odds On, Binary, Grave Descend, Drug of Choice, The Venom Business, Zero Cool, Scratch One, and Easy Go, and as Jeffrey Hudson, Case of Need.

The Andromeda Strain was something altogether different. In it, the military dispatches a special team to recover a top secret satellite that unexpectedly crashed down onto the small town of Piedmont, Arizona. When the team abruptly falls out of contact, the military discovers that everyone in the town (and their team) has died.

They suspect that some sort of pathogen hitched a ride down on the satellite, and activate a new mission: Wildfire. The project is led by a scientist named Jeremy Stone, and is designed to identify and contain the potential threat. He and his team suit up and visit the town, and find that everyone had indeed died. Whatever the satellite brought back, it quickly clotted their blood: people either fell over dead, or killed themselves when they saw their neighbors dying around them. There are only two survivors: a screaming infant, and an elderly man, who are taken in for study.

The novel leaps forward in leaps and bounds. As the Wildfire team works against the clock to figure out what the pathogen is, it’s changing: it seems to have the ability to eat away plastic, proving to be a containment risk, which in turn brings the risk of self-destruction.

The novel was something altogether different at the time. While science fiction was a well-established genre by the 1960s, Crichton brought a bit of a new viewpoint to what’s otherwise a science fiction story. He was a doctor by training, and brought that experience into a fast-moving thriller that could easily have taken place while the reader cracked open the book. It was a combination that brought millions of readers to the novel, and established Crichton as a household name.

Body of IP

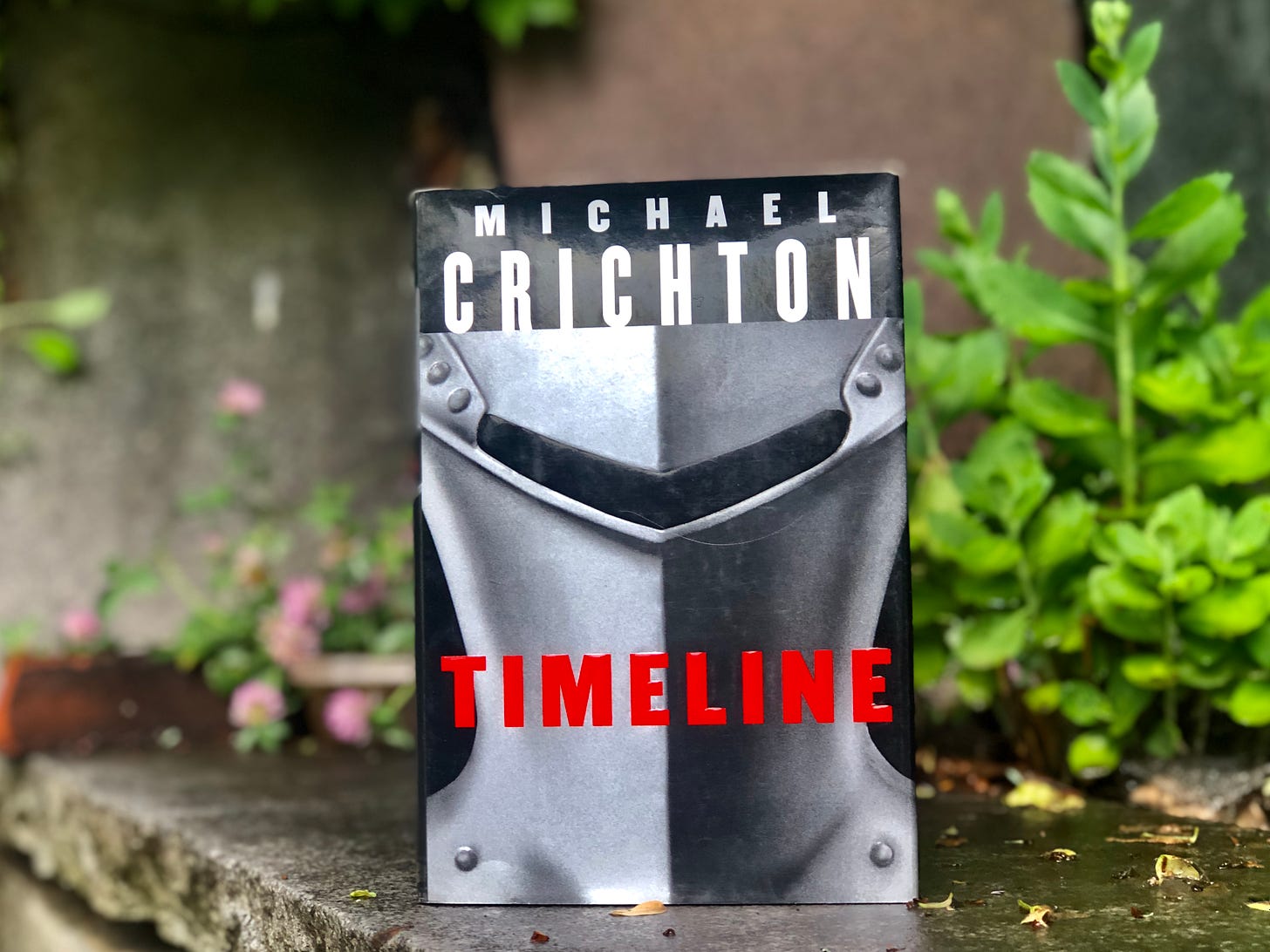

Crichton continued forward with this style of techno thriller, writing books like The Terminal Man, Sphere, Jurassic Park, Timeline, and others. He framed biology, physics, cybernetics, and genetics in ways that were accessible to readers, extrapolating out the exciting possibilities that science and technology could offer, and how they could be misused. (It should be noted that not all of his work or views were well-received: scientists heavily criticized his 2004 novel State of Fear for his dismissive take on climate change, while his book Next featured a sexual predator who was named after a writer who wrote a negative review of State of Fear.)

What’s more, Crichton’s formula was something that translated well to Hollywood, especially as CGI came into widespread use. Just a couple of years after The Andromeda Strain hit bookstores, Universal Pictures released an adaptation of the book. More followed: adaptations of The Terminal Man (1974), Congo (1995), Sphere (1998), and Timeline (2003), and as well as the sprawling Jurassic Park franchise, which has since grown to five films, with a sixth is in the works. He also wrote and directed several film projects: Westworld (1973) (which the latest HBO series reimagines), as well as Coma (1978), The First Great Train Robbery (1979), Looker (1981), and Runaway (1984).

Essentially, Crichton was something that was highly desirable to Hollywood studios: a well-known brand that produced reliably successful content, which flipped nicely to other mediums.

When Crichton died in 2008, he left behind his wife, Sherri (his fifth — they married in 2005) and unborn son. In the years since, Sherri has become the driving force behind the author’s resurgence, working to continue his legacy through a company called CrichtonSun, which houses Crichton’s archives and serves as a film and television production company.

Crichton also left behind thousands of documents and unfinished projects, which Sherri began to go through after his death. “He was always working on different books at any given time,” Sherri explained to me last fall, “researching new ideas that were intriguing to him and he would insert those ideas into a book at some point in the future.”

“When he died, I was absolutely devastated,” she explained. “I was pregnant with our son, and I knew from the get-go that to stay connected with Michael was through his work life, because that was something that was undiscovered for me at the time. I had no idea the breadth of his genius, other than knowing the things that he had created.” Going through her late husband’s papers was a way to keep his memory alive and was a way for her son to connect with the father that he would never know.

As she began going through his papers, she began to discover some projects that had largely been completed, but never published. In 2009, HarperCollins announced that they had discovered a historical novel, Pirate Latitudes, as well as part of a techno-thriller, Micro. Working with his estate, Pirate Latitudes hit stores in the fall of 2009, while they brought in The Hot Zone author Richard Preston to finish Micro, which hit stores in 2011.

At the time, his agent, Lynn Nesbit, indicated that they had only just scratched the surface, and that there could be other projects hidden away. That proved to be true. In 2016, HarperCollins announced that it would publish a new historical novel, Dragon Teeth, about a violent clash between two rival paleontologists in the 1800s during a period known as the “bone wars.”

Bringing out unpublished novels by dead authors has always been something of a controversial choice — most notably in 2015 with the release of Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird prequel Go Set A Watchmen, which she actually wrote before her famed novel, but which she had let sit in a drawer for decades.

Book critics worried that she had been manipulated into releasing the book, and that it might have been a cash grab from her publisher. There have been other examples, too: Robert A. Heinlein had left behind a longer version of The Number of the Beast, which he had edited down to its final version. A publisher, Phoenix Pick, working with his estate, recently released the longer version as The Pursuit of the Pankera. The two share the first third, but after that, it diverted into a completely different work. Which version did Heinlein really want audiences to read? Clearly, The Number of the Beast.

Incidents like this resurface a long-simmering question within the arts world: should an author’s unpublished or unfinished go before audiences, if said author didn’t finish them as intended? In Crichton’s case, his estate seems to have fallen onto the side of yes. Sherri Crichton explained that her motivating factor as one of continuing his legacy was that “his name stays relevant and continues to echo to a new generation, and to inspire people to read his back list of books.”

But there’s also the impulse to reimagine and realize the potential that his existing works bring. Universal Studios has worked to relaunch Jurassic Park as a cinematic franchise with Jurassic World and its string of sequels, while HBO has reimagined Westworld as a much more serious and dark fantasy about the implications of AI. “Let’s go back and look at what the possibility would have been to make a sequel to The Andromeda Strain, which is what really put him on the map,” Sherri said.

Notably, all three of Crichton’s posthumous novels quickly earned film deals, although none have been released as of 2020. Sherri Crichton noted that the estate is still working with Amblin Entertainment on an adaptation of Micro, and that they have another project in the works with Paramount Pictures.

Evolution

This is where Wilson’s The Andromeda Evolution comes into play. Unlike the works generated out of Crichton’s posthumous notes and papers, this new novel is an original.

Wilson is certainly well-suited to follow in Crichton’s legacy. Robopocalypse and its sequel Robogenesis aside, he earned his PhD in Robotics from Carnegie Mellon University in 2005, with a thesis titled “Assistive Intelligent Environments for Automatic In-Home Health Monitoring.” That experience has certainly influenced his writing career, in which includes books like Amped, Robot Uprisings (co-edited with John Joseph Adams), and The Clockwork Dynasty.

“I got to spend a lot of time getting a PhD in Robotics, which I never used except to write science fiction that’s believable,” Wilson says. “Michael Crichton used his medical degree to write incredible fiction. He drew on that a lot, and it’s clear in his writing because he knows what he’s talking about.”

“There is a parallel there. I could just as easily be a scientist. I like science! I like the scientific mindset, solving problems, moving methodically, utilizing technology in novel ways to solve new problems, and I love all of that in Crichton’s novels.”

With The Andromeda Evolution, he is simultaneously exploring the potential of Crichton’s body of work, and rebooting it for a new generation of readers.

It’s en vogue right now for the latest Hollywood sequels to scaffold off of their predecessors: rather than a straight up remake, writers and directors set their sequels in real time, allowing a generation of former A-Listers to reprise the roles that made their careers for one last hurrah, before turning over the reins to a new generation of actors who can presumably relaunch the franchise for a new generation. Examples include Star Wars: The Force Awakens, Rambo: Last Blood, Creed, Prometheus / Alien: Covenant, Star Trek, and others.

Wilson discovered Crichton’s books when he was a teenager. “I proceeded to read every one of them that I could get my hands on,” he explained. “Eventually I became a writer, and when Robopocalypse came out, there were all these comparisons to Michael Crichton. I was really flattered by that.”

When it was released in 2011, Robopocalypse became a smash hit that you rarely see occur: Annalee Newitz noted in their review on io9 that the book is “a blockbuster premise wrapped around a true science fiction tale that could change the way you think about robots, and the humans they live with.” And it gained plenty of attention in Hollywood: even before it hit shelves, Steven Spielberg was slated to direct an adaptation of the book, with an eye towards releasing it in 2013. Chris Hemsworth, Ben Whishaw, and Anne Hathaway were slated to star. Ultimately, the project collapsed and Spielberg moved onto other things, and as of 2018, Michael Bay is expected to direct the adaptation.

Spielberg shifted focus from Robopocalypse to another adaptation: Ernie Cline’s Ready Player One. The two authors were friends, and Cline gave Wilson a call. “He had sort of a strange request,” Wilson explained. “He told me that CrichtonSun was looking for someone to work on a Crichton-related project. It was all very top secret.”

Wilson had just published a new novel, Clockwork Dynasty, and was on tour. “I was in LA, and I had what I felt like was a really informal meeting,” he says, “but it turned out that CrichtonSun had been vetting authors for a really long time, and they had been waiting for the stars to align to find the right person.”

“I had this conversation about what I loved about Crichton and which books I liked, and which were my favorite parts. It was easy for me to talk about, right? Obviously, it was a little bit of a test.”

It was a test that he passed. Crichton’s estate invited Wilson to come back and pitch them some ideas and had a brainstorming session about what he’d like to do. “The Andromeda Strain in particular has just an incredibly deep mythology beneath it with a lot of unanswered questions about where it came from and what it is. That first novel really teases the audience, because it’s a voyage of discovery: you’re watching real scientists figuring out real things, running real experiments, trying to track this thing down, and in the end, you have more questions than answers.”

That pile of questions afforded Wilson with plenty of possibilities for a potential sequel. “There were a million directions to go and a million ideas to explore,” he says. Along the way, the estate kept a close eye on how the project developed. “It was built in that CrichtonSun could come in and say “It’s not working,” and shut it down. “This was a real tightrope because it had to be perfect in a lot of ways, and we just never fell off,” Wilson says.

That’s a typical arrangement for anyone who writes tie-in fiction, where you’re playing in someone else’s sandbox. Such works are by their very nature a collaborative experience, in which writers provide the words and stories, and IP holders ensure that said writers are coloring within the lines, to maintain story continuity, franchise tone, or that it’s simply something that will line up with the expectations of their consumers. Evolution feels a bit like this: it certainly lines up with the original novel (and even casts Michael Crichton as a real figure within the world), and it maintains the same sort of approach to the material that Crichton is known for.

Wilson explains that his approach to the story was to take the events presented in The Andromeda Strain as “gospel truth.”

“That’s why that novel is fun: it’s so believable, right? All those characters, everything that happened, it all really happened. If people tell you it didn’t happen, or tell you that Piedmont Arizona doesn’t exist, they’re just trying to cover it up. That’s the key to capturing the wonder of the first novel.”

With that in mind, he took the book as a foundation, and advanced everything by half a century: characters have grown up and died, technology has advanced, and scientists around the world have studied the microorganism in the years since it took place. “I really just let the Andromeda strain exist for fifty years, and then picked it all up and moved forward.”

At the end of Andromeda Strain, Crichton’s pathogen appears to have settled in Earth’s upper atmosphere after mutating into a less deadly version. In the years that followed, scientists continued to study it in safe environments, like on the International Space Station. Everything changes when a Chinese space station crashes down to Earth, and a drone spots a strange structure growing out of the Brazilian jungle in an area that’s inhabited only by uncontacted tribes. The discovery activates the watchdog group that’s been waiting and watching for years for a reemergence of the Andromeda pathogen. Quickly, a team is dispatched in to the jungle to investigate, guarded by a team of mercenaries.

What they find is something stranger and deadlier than they expect. They’re attacked by members of an uncontacted tribe, seemingly driven mad by the infection. The scientists lose their protective detail, and eventually reach the structure, and go in to explore it.

From there, it everything goes a bit bonkers: the alien pathogen might be a defensive mechanism sent out from an alien civilization, designed to stagnate any potential competitors from rising up throughout the galaxy. Or it might be an elaborate puzzle designed to test a civilization’s advancement. Either way, some shadowy scientists have hijacked it (and the ISS) to create a massive space elevator that could ease humanity’s access into space. The plot is either a clever workaround from being trapped on the planet, or something that could doom us to oblivion.

By the end of the novel, the pathogen ends up settling in the depths of Saturn’s atmosphere sending out a radio signal into deep space, clearly teeing readers up for a potential sequel. The book plays out much like the work it follows: scientists encounter problem, and set about working out the details to figure out what they’re up against.

Crichtonverse

If there’s any rule of thumb for franchise IP, it’s that companies and studios will seek to extract value from it for as long as people will continue to pay money for it. For massive franchises like Star Trek and Star Wars, that’s a relatively easy task, given their respective sizes, numbers of characters, and visibility within the marketplace. Others sort of meander along, such as Joss Whedon’s Firefly comes to mind, which has enjoyed a low-level of success after TV and film with a series of comic books, and more recently, a series of novels. The work that Crichton left when he died is particularly attractive, especially with a series of high-profile adaptations in the form of Westworld and Jurassic World at the forefront of the public’s attention.

It’s clear that Crichton’s existing body of work is a durable foundation to build off of, and The Andromeda Evolution seems to be the first attempt at seeing what can come out of such an effort. Wilson works from that original novel faithfully, but blows it up into something much bigger, introducing some new concepts that feel modern, but Crichtoneque. And while they wouldn’t provide any firm details, both Wilson and Sherri Crichton indicated that there are plans to continue to play with the building blocks in some form or another.

What could that look like? Certainly, I can see a sequel to Evolution that continues the storyline that Wilson dreamed up. And there are other instances where I can see CrichtonSun bringing in an author to play with some of his other novels in a similar fashion. Take The Terminal Man, for example: it’s about a man who suffers from violent episodes after he was in a car accident, and is implanted with a device to try and regular his brain’s reaction. As is typical with a Crichton novel, the technology has some unexpected problems. Given that the fields of neuroscience and technology have advanced considerably in the years since it was published, there’s lots of potential for someone to pick up that particular storyline and run with it.

Crichton’s first contact / time travel novel Sphere is another good example, about a team of scientists investigating a massive spacecraft that’s been discovered on the bottom of the ocean, which ends with all of the characters trying to avoid further problems by wiping their memories. Timeline is another time travel novel in which a team of scientists are transported back in time to try and rescue a missing scientist — again, there’s plenty of potential there for additional takes and stories with that technology. And of course there’s Jurassic Park and The Lost World, which have their own spinoffs in cinematic form. I don’t think that dinosaurs will ever go out of style.

But while publishers and studios might want to wring as much value out of a property , spinoffs and continuation of said IP only works longterm if it adheres to the content that it’s replicating. There’s a big reason why I think The Force Awakens and Rogue One are amongst the better and well-liked Star Wars spinoffs: they borrow heavily from the stories and design language of the originals, reminding people of why they fell in love with Star Wars in the first place. There are certainly spinoffs that don’t work: take your pick from any franchise. Wilson seems to have the right approach to this story, although I thought that it went a little too bonkers by the last third, to the point where it stretched away from the Crichtonesque take on reality to something a little more Michael Bay. It’s a bit of a minor quibble, given the types of things that Crichton was known for writing about.

Will CrichtonSun be able to scale up from the foundational works that it has at its disposal? It’s certainly possible that we’ll see more original novels come out of Crichton’s archives and papers. I wasn’t a huge fan of Micro or Dragon Teeth, but The Andromeda Evolution feels like a step in the right direction, and while I don’t think it’s as good as Crichton’s best works (although it’s certainly better than some of his lesser novels) I think it’s certainly possible.

But whatever efforts Crichton’s estate makes will depend on how closely it adheres to the most basic elements of a Crichton novel: cutting edge science, and authors who are also scientists who can easily convey those complicated concepts for casual readers. Authors such as Ian Tregillis (PhD in physics, author of The Mechanical, The Rising, and The Liberation) and Janelle Shane (PhD in electrical engineering, and author of You Look Like A Thing And I Love You) feel as though they would be good candidates to tackle Crichton’s legacy and build upon it.

That’s a hard mark to hit, and CrichtonSun runs the significant risk of simply cashing in on the power of the Crichton name and turning out garbage thrillers each month that neither honor his legacy or build upon it. But by building on the name, they’re ensuring that Crichton’s name and works will live on, rather than coasting along on sales that will inevitably dwindle with time as others pick up the techno-thriller reins. Whether or not Evolution hits the exact mark that Crichton left behind isn’t really the point — it’s proof that Crichton’s heirs are actively pushing his name forward and continuing that line of thinking forward. Hopefully, it’ll continue to work, providing readers with plenty of new adventures to dig into.

Thank you for reading, and thanks for your subscription: that’s what allows me to take on projects like this. This story in particular was a casualty of the the Barnes & Noble' Sci-Fi and Fantasy Blog’s closure, and I wasn’t sure that I’d be able to explore it in the way that I wanted. Thanks to you, I’ve been able to do that.

Stay tuned for another paid letter in the nearish future, as well as the usual mix of things.

Andrew