Nostalgic Adventures and Racism as Cosmic Horror

Hello!

I feel like I’ve been in a bit of a lull the last week. I’ve had plenty to do, and plenty to read (and I have been busy), but it feels like it’s one of those weeks (or months) where the results of that work isn’t going to pay off for a while yet. For someone who’s been increasingly tying their self-worth to their work output, it’s not exactly healthy. Fortunately, the kids are off at daycare, which has given me some time to write and think.

Some of that work is coming to fruition: last week, I released the first of what I’m calling Reading List+, the paid version of this newsletter. That letter was a long look at the problems that J.K. Rowling and Richard K. Morgan have created for themselves by boosting some anti-trans rhetoric, and what the impact of that might be. The next paid letter will be going out sometime next week, and it’ll be a deeper dive into the Crichtonverse — how Michael Crichton’s estate is building on his legacy, and what the future might hold. I’ve got other things in the works as well, which I’m excited about, and which should be fun to write. I guess that’s a bit of motivation right there.

Okay, on to your regular newsletter content. Today is the 20th anniversary of the animated film Titan AE hitting theaters, a film that’s near and dear to my heart, and I have some thoughts on N.K. Jemisin’s latest novel, The City We Became.

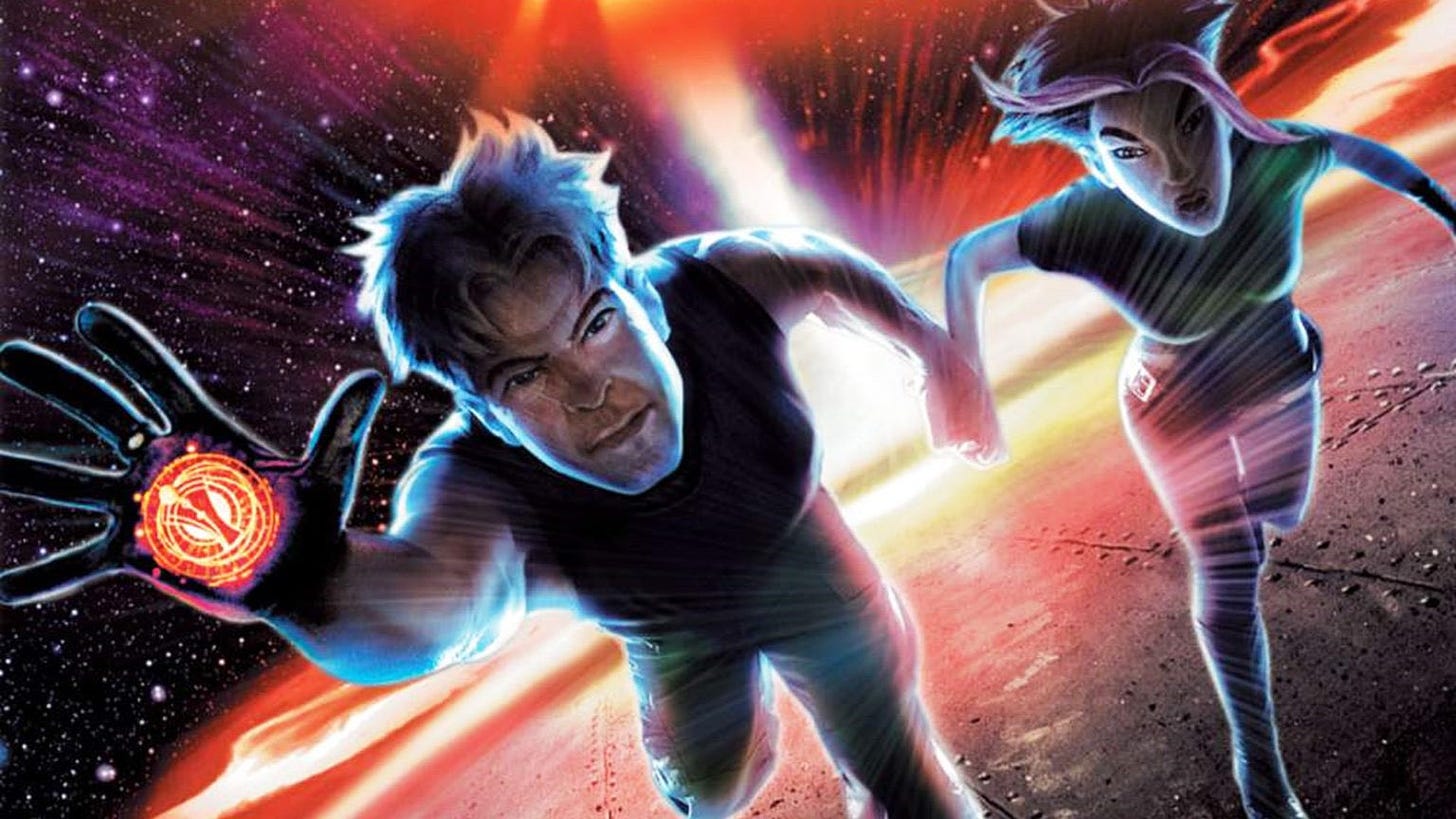

When the Adventure Begins: 20 Years of Titan AE

When I was 15, I was a counselor in training at YMCA Camp Abnaki. That was a wonderful, formative summer: I made some lifelong friends that I still talk with 20 years later, and it’s generally one of those times in my life that I look back on fondly.

CITs were the workhorses of the camp. We helped regular counselors (with the idea that we’d come back a year later as proper employees), cleaned dishes, did team building exercises, and so forth. On the weekends during changeover (when one group of kids left and another arrived), we’d go out to town as a group to do something, like go to a baseball game or a movie.

It was that summer that I caught a movie that really blew my mind and which has stuck with me ever since: Titan AE.

I was completely caught up with Star Wars at 15. I’d seen the Special Editions when they hit a couple of years earlier, and The Phantom Menace had hit theaters the summer before, and I was devouring Star Wars novels at a healthy rate. I was beginning to dip my toes into other waters, like books from Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, and Frank Herbert. That summer, a fellow CIT, Sam introduced me to Dungeons & Dragons and Babylon 5. Our shared interests in fantasy and science fiction has since led to a life-long friendship, but what really cemented it, I think, was going to see Titan AE.

The film has since become one of those weird forgotten films that gets the “deep cut” placement on the “# Science Fiction films you should check out “ sort of lists. Set in the distant future, humanity has made its way to the stars, where it found a dangerous enemy: the Drej, an energy-based alien species that decides that we’re too dangerous of a species to let live, figures out where Earth is and destroys it in a Death Star-like attack. That’s just in the first fifteen minutes.

What blew me away with the movie back in 2000 was what came next: a cynical, thrilling take on humanity’s place in the cosmos. The Drej’s attack on Earth worked. Without a home world, the surviving humans drift apart in colony ships, taking odd jobs, and hoping that they can find a new place to live before they completely die out. Rather than taking over the galaxy, like we see in just about every other science fiction movie or TV series, we’re not even at the bottom rung of the latter: we’re hanging on for dear life.

Humanity’s salvation comes in an unlikely form: Cale Tucker, the son of a scientist who spearheaded a project called Titan, which could create an entirely new planet for humanity to settle. When the Drej attacked Earth, Sam Tucker took off with the Titan, and left Cale with the key to finding it. 15 years later, one of Tucker’s associates tracks down Cale and convinces him to help find the long-lost ship. Adventures ensue: there are daring rescues, shocking betrayals, and some stunning visuals as they cross the galaxy. For a 15 year old Star Wars fan, it mashed all of the right buttons.

When you fast forward years and decades on anything, and there’s a good chance that that thing you liked won’t be as interesting or cool as when you first saw it. Chalk that up to time, changing tastes, maturation, or a better understanding of what said thing is. To refer back to last week’s letter, J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series makes for a good example. I loved those books while when I read them, but I’m not sure I can go back to them quite with the same mindset, or same enjoyment.

Today marks the 20th anniversary of Titan AE’s release into theaters, and last night, I introduced the movie to Bram. He was glued to the screen, and so was I. While I’ve seen the film dozens of times over the years, watching it again with that milestone in mind made me realize just how good it remains.

Sure, it’s dated a bit in some places: the animation is comical compared to what we have today. Drew Barrymore playing Akira (a character of Asian descent) wouldn’t fly today. But those issues aside, it’s a film with a certain nuance to it: it plays with themes of racism (speciesism?) and acceptance, portrays the surviving human civilization as multicultural and features a fairly diverse group of characters. And it looks absolutely stunning: the “wake angels” scene in which the Valkyrie flies through a nebula rates amongst one of the most gorgeous scenes in science fiction cinema in my view.

Plus, it was a technical achievement. It utilized a lot of CGI animation, some of which hasn’t aged particularly well, but which feels like it was a breath of fresh air at the time. There are some dynamic shots as the camera pans wildly around the characters, giving it a sense of motion and action, something that wasn’t really doable or seen with animation prior to that point. And it was the first film to be sent to theaters digitally, rather than be transferred to film for projection.

Watching the film, I’m struck at how it’s a project that would probably never be made today: an animated film featuring an original story set in space, unconnected to any sort of franchise or existing property. And more than that: it’s a *dark* film. Humanity is brutally exterminated in the film’s opening minutes. Cale and other humans face racism from other aliens in the galaxy and are on their way to being wiped out. They’re pursued by a relentless alien civilization, and when everything seems to be going well, we see one character heartlessly betray the rest of the team. There’s also slavery, characters are graphically killed in fights (poor Cook), and so forth.

But there’s a lot of hope wrapped up in it, too. Akira, the Valkyrie’s pilot, is relentlessly optimistic about the prospects of humanity, and eventually steers Cale to doing the right thing. The film is full of the theme of rebirth, from central purpose of the Titan (a massive world-builder ship), to characters waking up after being presumed dead or lost, and changing their deeply-held convictions.

Animated films are often held up as childish or simple projects, but I think the reason that I keep coming back to Titan AE even two decades later is that it’s not a simple film. It’s funny and full of action, but it’s thought-provoking, serious, and memorable.

And there’s a sense that this film is the tip of an iceberg. The film drops you right into the action with very little explanation: aliens want to destroy humanity for some nebulous reasons (they see humanity as an existential threat, and given what Cale does to them, I can sort of understand why), but there’s no backstory to how we get to that point. There’s a network of alien civilizations that come together on asteroid stations to trade or resupply, but it feels like we’re just grazing the edge of a much bigger alien diaspora. There are mysterious alien civilizations that feel truly alien. And there’s the remains of humanity, clustered together on cobbled-together ships. All of that leads to the promise of a much bigger story humming along in the background.

For years, I’ve wondered if anyone would take a stab at returning to Titan AE, to flesh out its world a bit more and see what happens next. I don’t know if that’s actually a possibility, or if it’s even a franchise that a studio would ever consider taking on: the original film bombed at the box office, so much so that Fox Animation Studios — despite the technical advancements made on the film — ended up closing down. But I think it’s a film that was a bit ahead of its time, and it feels like it’s a property that something like Disney + could do something with. There’s certainly a drive for new content on the parts of streaming services.

Or the film could remain what it’s been for 20 years: a largely forgotten film with some notable technical achievements that sometimes pops up in discussions between fans, and which surprises new viewers when they track it down and give it a watch. I for one, am glad that it holds up after those two decades, and I’m glad for the memories that it brings back from that summer in 2000.

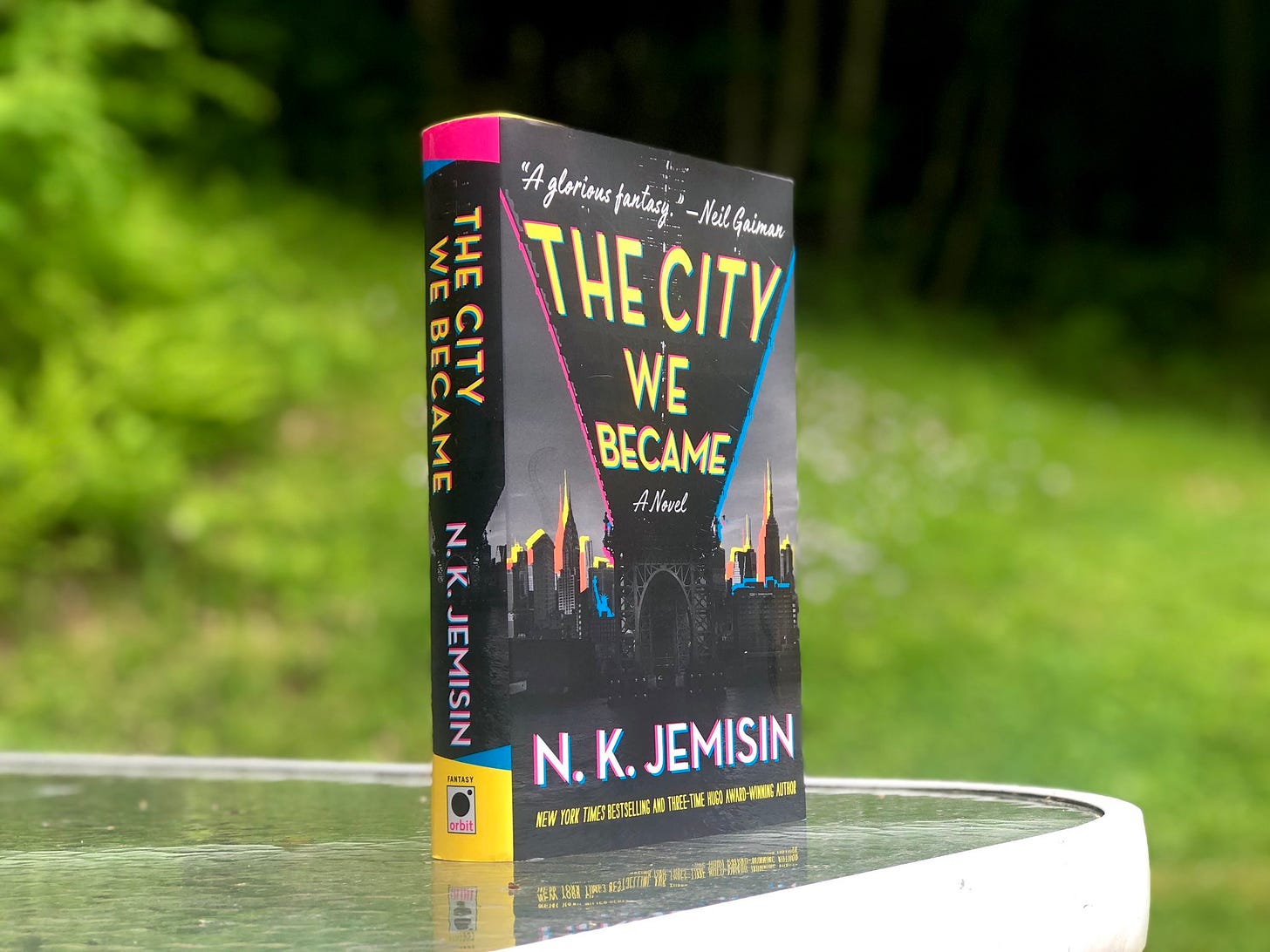

Love Letter to New York City: N.K. Jemisin’s The City We Became

The last couple of years have been a whirlwind for the science fiction and fantasy community, with a whole host of scandals like Sad/Rabid Puppies, Gamergate, and the Lovecraft / World Fantasy Award highlighting the need for the community to grapple with both the changing demographics of Fandom, but also the realization that the genre has deep-seated issues that it needs to work out if it’s going to remain around as a community.

We’re now starting to see those events trickle over into the content that the community is consuming. Books like Nnedi Okorafor’s Lagoon (inspired by Okorafor’s anger at racism in District 9), Chris Kluwe’s Otaku (a book that feels like it’s been inspired by the fallout of Gamergate), and now N.K. Jemisin’s The City We Became, a powerful punch of a book that pushes back against the systemic racism in the United States, and one that provides a counterpoint to the works and worldview of H.P. Lovecraft.

Jemisin has been a rising star within the world of fantasy literature, and in many ways, that’s made her a target for racist fans who dislike her stature, her views, and the fact that she won the Hugo Award for three years running for her Broken Earth trilogy. In her acceptance speech for The Stone Sky back in 2018, she addressed the struggle:

I have smiled and nodded while well-meaning magazine editors advised me to tone down my allegories and anger. (I didn’t.) I have gritted my teeth while an established professional writer went on a ten-minute tirade at me—as a proxy for basically all black people—for mentioning underrepresentation in the sciences. I have kept writing even though my first novel, The Killing Moon, was initially rejected on the assumption that only black people would ever possibly want to read the work of a black writer. I have raised my voice to talk back over fellow panelists who tried to talk over me about my own damn life. I have fought myself, and the little voice inside me that constantly, still, whispers that I should just keep my head down and shut up and let the real writers talk.

But this is the year in which I get to smile at all of those naysayers—every single mediocre insecure wannabe who fixes their mouth to suggest that I do not belong on this stage, that people like me cannot possibly have earned such an honor, that when they win it it’s meritocracy but when we win it it’s “identity politics” — I get to smile at those people, and lift a massive, shining, rocket-shaped middle finger in their direction.

The City We Became feels like a natural evolution of her career, a shift from second-world fantasy to an alternate version of our own world, one that’s all-too-painfully recognizable. in 2016, Jemisin published “The City Born Great”, a fantastic short story about the birth of an avatar for New York City — a manifestation of the city in human form, and the otherworldly horror that they face.

Jemisin has now expanded upon that shorter story, unfolding it like a piece of origami to show that a much greater story is at play. Now in novel form, that initial birth of New York City has gone wrong: the avatar has been hurt, and it’s hibernating, as the forces that worked so hard to take down the city regroup and prepare to strike again. New York, however, is a special place: it’s inhabited by not just one avatar, but one for each of its boroughs. Matty (Manhattan) arrives in the city only to forget his past and who he is; Brooklyn is a former rap star turned city councilwoman. Bronca (Bronx) is a tough Lenape woman who directs an arts center, Padmini Prakash (Queens) is an Indian student, and Aislyn Houlihan (Staten Island) is a young white woman who’s terrified of the others.

The enemy they’re facing off against is the Woman in White, who’s bent on destroying the city and all that it represents. She’s begun to infect the city with tendrils that seem to enhance people’s divisive urges, nudging them gently towards intolerance and bigotry. It seems as though she’s been at it a long time, setting up foundations that work to gentrify neighborhoods, backs racist artists trying to make high-profile viral “statements,” and so forth.

Unlike The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms and The Fifth Season, Jemisin sets up a story that’s far more straight forward: the five avatars have to figure out how to find one another and work together to save their home as the city is slowly taken over by the Woman in White and the otherworldly horrors that she brings with her. The novel is a fast read, but it’s no less weighty. Where Jemisin’s commentary on the world was wrapped up in second-world fantastic allegory, she brings out the message carved onto a two-by-four. It makes for a powerful read, one that puts forward not only the overt moments of racism against black people, but some of the more subtle ones as well.

In a lot of ways, the novel serves as a counterpoint to Lovecraft’s “The Horror at Red Hook” — it even directly references it. Lovecraft was famously xenophobic, and that story in particular focused his racist eye on the impoverished slums that were the Red Hook neighborhood. While it’s tempting to push Lovecraft to the side, refitting his brand of cosmic horror to work counter to his views is a delicious thing to read.

(Jemisin isn’t the first to address Lovecraft’s work: Victor Lavalle did that as well in his own novella The Ballad of Black Tom.)

If the five avatars represent New York City, the Woman in White is one for all of white America. The implications are readily apparent: a malevolent entity that seeks to subjugate and oppress others to maintain power. It’s imagery that Jemisin’s used before — (although I’m not sure if it’s expressly connected): the White Lady in her short story “Red Dirt Witch” — and it’s an extremely effective tool, particularly when she follows Staten Island, a young woman who’s surrounded by subtle and overt forms of white supremacy in a part of the city that’s a far cry from the diverse and liberal streets of its neighbors. Jemisin shows off how effectively insidious fear is as a means of division, something that plays out in a critical way by the end of the novel.

Reading this book over the last couple of weeks has been an interesting experience: I finished it right after a Minneapolis police officer killer George Floyd and after a racist woman called the cops when Christian Cooper asked her to leash her dog in New York City, and it’s been on my mind as protests have swept across the nation. There are so many points in the book that are drawn from the fabric of our world: angry white people who call the cops on “suspicious looking” neighbors, police officers who are connected to white supremacists, the weight of white America pushing down on the black and brown citizens of this country. It might be cosmic horror, but isn’t that pretty much what we’re living through now?

Currently Reading

I’ve been off my game a bit reading this week, and haven’t advanced too much in the books that I’ve had on my list. Instead, I’ve been listening to a pair of podcasts: Headlong’s Running from COPS and Leon Neyfakh’s Fiasco.

Running from COPS is particularly relevant right now: Paramount just canceled the long-running series amidst the nation-wide protests. I guess that’s one way to defund the police. Like just about everybody, I’ve watched the show over the years, although it’s never really been something that I’d seek out: it’s one of those hey-it’s-on-tv-while-we’re-in-a-hotel-room sort of thing.

This podcast series is eye opening: it’s a deep-dive into how the show is made, and how it portrays policing, which surprise!, which it actually really doesn’t. The producers apparently use sketchy tactics to get consent from subjects, the types of crimes it portrays is way out of whack with what’s actually going on, and it tends to be outright propaganda for police departments. None of which really flies in 2020. It’s 6 episodes long, and it’s a very good bingable listen.

I’ve been a fan of Leon Neyfakh’s work since he launched Slow Burn on Slate, and last year, he jumped over to Luminary (a premium podcast platform) for a new series called Fiasco, which is pretty much the same as Slow Burn: a deep dive into some sort of issue in American history. Slow Burn covered the Nixon and Clinton impeachments, and for this series, he covered Florida recount during the 2000 presidential election, and in this latest season, he tackles the Iran-Contra scandal, which is riveting. I highly recommend it, but you’d have to sign up for Luminary.

I’m now on the hunt for others — lemme know if you have any favorites that are a) narrative in structure (ie, not two dudes gabbing behind a microphone), b) newish, and c) something interesting about history or politics. One I have on my radar is Blockbuster: The Story of James Cameron from Epicleff Media. I enjoyed their take on George Lucas and Star Wars last year.

On the book list right now? Mary Robinette Kowal’s The Relentless Moon, Robert Jackson Bennet’s Shorefall, Chris Kluwe’s Otaku and Martha Well’s Network Effect. Oh, and Frank Herbert’s Dune.

Further Reading

- The Art of Rendezvous with Rama. I spoke with Matt Griffin about his artwork for The Folio Society’s new edition of Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendezvous With Rama.

- A campless summer. The Atlantic has a good read up on the value of summer camps, and what we might lose when they’re all closed for the summer because of COVID-19.

- A Desolation Called Peace Reveal. io9 reveals the cover and an excerpt of Arkady Martine’s next novel, A Desolation Called Peace, her sequel to her fantastic debut book A Memory Called Empire.

- Library Warfare. As the pandemic flared up this spring, the Internet Archive announced that it was opening up an “Emergency Library,” an archive loaded with scanned books that they didn’t really have permission to lend out enmass. Protocol has a good overview of the situation and its implications, as does The New York Times.

- Salvaging the SWEU. There’s a rumor floating around that we might see a live-action Grand Admiral Thrawn. I’m not sure I’d trust it, but it gave me something to think about when it comes to what we could salvage from the Star Wars Expanded Universe.

- Tainted legacy. Isaac Asimov’s legacy isn’t aging well in the last couple of years. He certainly would have been #MeToo’ed out of the industry had he been alive today. Lithub has a good overview of his horrible attitude towards women.

That’s all I’ve got for now. As always, thank you for reading. Let me know what you’re reading and what your thoughts are.

Next issue will be a paid one, and I’m pretty excited for this particular piece. If you’re interested in reading up on Michael Crichton, IP, and why you might see his name pop up again, subscribe here.

Andrew