P. Djèlí Clark’s Ring Shout reimagines Lovecraftian horror

Reimagining Lovecraft, Robin Hobb on The Farseer Trilogy, and more

Hello!

I hope that you’ve been faring well in the last couple of weeks. One of the things that I’ve found myself doing the last couple of months is work around the house, activities that keep me focused on a singular task. My latest project has been some reconstructive work on the decrepit garage next to my house.

So, I bought some boards and cut them down to size, tore off the stuff that was rotting and falling apart. It’s not 100% perfect, but for a couple of years? It’ll do. This week has been devoted to paint: the main coat went on earlier this week, and it’s a huge improvement over the primer that I painted on. I did the trim yesterday, and the shade of green is just off enough that it’s bothering me. I’m hoping that a second coat will darken it up, but we’ll see.

It’s all a stop-gap measure. We’ll knock it down eventually and replace it with something better, but I figure a bit of preventative maintenance will put that off for a while.

This week: some thoughts on P. Djèlí Clark’s new book Ring Shout, I spoke with Robin Hobb about the 25th anniversary of Assassin’s Appprentice and why it holds up, a preview of yesterday’s big Dragonlance piece, and the usual look at what I’ve been reading in book form and around the internet.

Flipping Lovecraft

I recently blew through P. Djèlí Clark’s short novel Ring Shout. It’s a topical book for 2020, especially as the country deals with the issue of race inequality and racism. As the cover suggests, it’s a story that deals with the racism of the Ku Klux Klan, the terror group that arose in the aftermath of the Civil War, and again around the 1920s.

It follows a woman named Maryse Boudreaux and her companions as they contend with a rising tide of racism in the country in the aftermath of the First World War. Clark puts a supernatural spin on the movement, revealing that our reality is under attack from another dimension, with otherworldly creatures feeding off of the hatred and anger that drove that movement. They’re slowly infiltrating the ranks of the KKK, and are close to breaking through and taking over. Boudreaux can see these creatures, called Ku Kluxes, and she and her friends have been taking the fight to them, little by little, trying to stem the tide.

The book is a fast-paced, gripping thriller: I could hardly put it down, and Clark masterfully ups the tension, dropping the reader into the midst of a pitched battle, and quickly upping the stakes to really put pressure on the characters as the goals of the Ku Kluxes becomes more apparent.

The novel makes for a nice accompaniment for another recent novel, N.K. Jemisin’s The City We Became, in which she explores the modern state of racism through gentrification and white exceptionalism and fragility in New York City. In both books, we see otherworldly terror used as a metaphor for systemic racism, and Clark’s work taps into that systematic horror that groups like the KKK brought with to the people it sought to oppress.

This is a topic that’s been top of mind for me in recent years, and it’s something that I touched on earlier this year with my interview with Lovecraft Country author Matt Ruff, and my thoughts on The City We Became shortly after it was released. Along with books like Victor LaValle’s The Ballad of Black Tom and Ruthanna Emrys’ Winter Tide, there’s a growing movement to take the racist legacy that is H.P. Lovecraft, and subvert his cosmic horror and use the tropes as a way to point to the very real horrors that racism and bigotry holds for the people it targets. Jemisin, LaValle, Clark, and Emrys all center their stories on the marginalized: people who would were seen by Lovecraft (and even his modern fans) as undesirable, and putting the traditional systems of power that might have otherwise been heroic for Lovecraft on the other end of the equation.

This, I think is why Lovecraft’s cosmic horror still works, and are stronger when you incorporate the real world history. As Ruff said in our interview, Lovecraft isn’t going anywhere — he’s too deeply embedded in the DNA of the genre. But Lovecraft’s fear and anxiety about the state of the world isn’t limited just to him, and if you change up details of ‘Shadow Over Innsmouth’, you “could easily be a story of a black traveler getting stranded in a sundown town.”

People fighting against an incursion of evil was absolutely a story Lovecraft has written. But Ring Shout has the backing of aa better understanding of history behind it, something the wider public is finally getting an idea about as we see statues of racists being toppled around the country. It’s a powerful little book, and one of a struggle I hope that we’ll see more of in the future.

Dragonlance changed how we read fantasy

As part of the more focused mission of this newsletter, I’ve been working to devote some more time to some more in-depth posts for paying subscribers. Here’s a selection of what I’ve released recently:

If you went to a bookstore’s science fiction and fantasy section starting in the mid-1980s, you’d likely encounter a block of novels taking up an entire shelf or two: Dragonlance. Originally created by game designer Tracy Hickman and co-written by Margaret Weis for TSR’s Dungeons & Dragons, the Dragonlance novels were part of a much larger multimedia franchise that accompanied hundreds of short stories and modules that supported the game itself.

The book series was a popular segment of fantasy literature through the 1990s, an outgrowth of the popularity of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings in the 1970s, and the authors that followed like Terry Brooks, Glen Cook, Robin Hobb, Robert Jordan, Mercedes Lackey, George R.R. Martin, and Michael A. Stackpole. But while stories like Wheel of Time and Game of Thrones have reached household recognition, Dragonlance has always felt like one of those franchises that’s been quietly influential for millions of fantasy readers, while at the same time was studiously ignored by the more established fandom for the genre.

Despite that, the series changed how fans, readers, and writers alike experience, interpret, and create fantasy literature, and why word of a revival of the franchise would have been big news. Earlier this week, Wired reporter Cecilia D’Anastasio reported that Hickman and Weis have filed a lawsuit against Wizards of the Coast for breach of contract after the company reportedly tanked an in-progress trilogy of novels that would have been their triumphant return to the franchise after being away from it for more than a decade.

The move begs a look into the story of how Dragonlance came to be, what its impact was on the world of fantasy literature, and the nature of franchise writing that the series helped pioneer.

You can read the full post here.

I want to illustrate some of the work that went into that 4500 word post. The whole thing took about three days to write, and involved researching the background of Dragonlance and D&D, conducting interviews with knowledgable people, then writing and rewriting. I feel strongly that this newsletter should be a resource for reported writing and commentary about the things we’re all fans of.

Some other posts that have gone up recently for paid subscribers:

- An audio version of the Christopher Brown interview.

- A short story that I wrote earlier this summer, “Walk in the Woods,” about accessibility, technology, and the outdoors.

- “What’s in my Bag” in which I talk a bit about what I’ve been carrying around in recent months when I’ve been getting outside or traveling.

- Dune is migrating to 2021, which looks at what this means for theaters.

I’ve got a couple of others on the way: one about radicalization in fandom, another about horror and nature. And a couple of other things on my mind is a history of Walden Tapes, and a longer feature about a military wargaming exercise that I took part in a year ago.

Hopefully, I haven’t put you off by making this sound like an ad: that’s not my intention! But, I hope that this is work that you value. There’s a small contingent of you who have subscribed, and that helps underwrite this type of research and reporting. So, if you’re interested in supporting that and this type of work, please consider signing up for a subscription, and help spread the word.

Robin Hobb’s The Farseer Trilogy

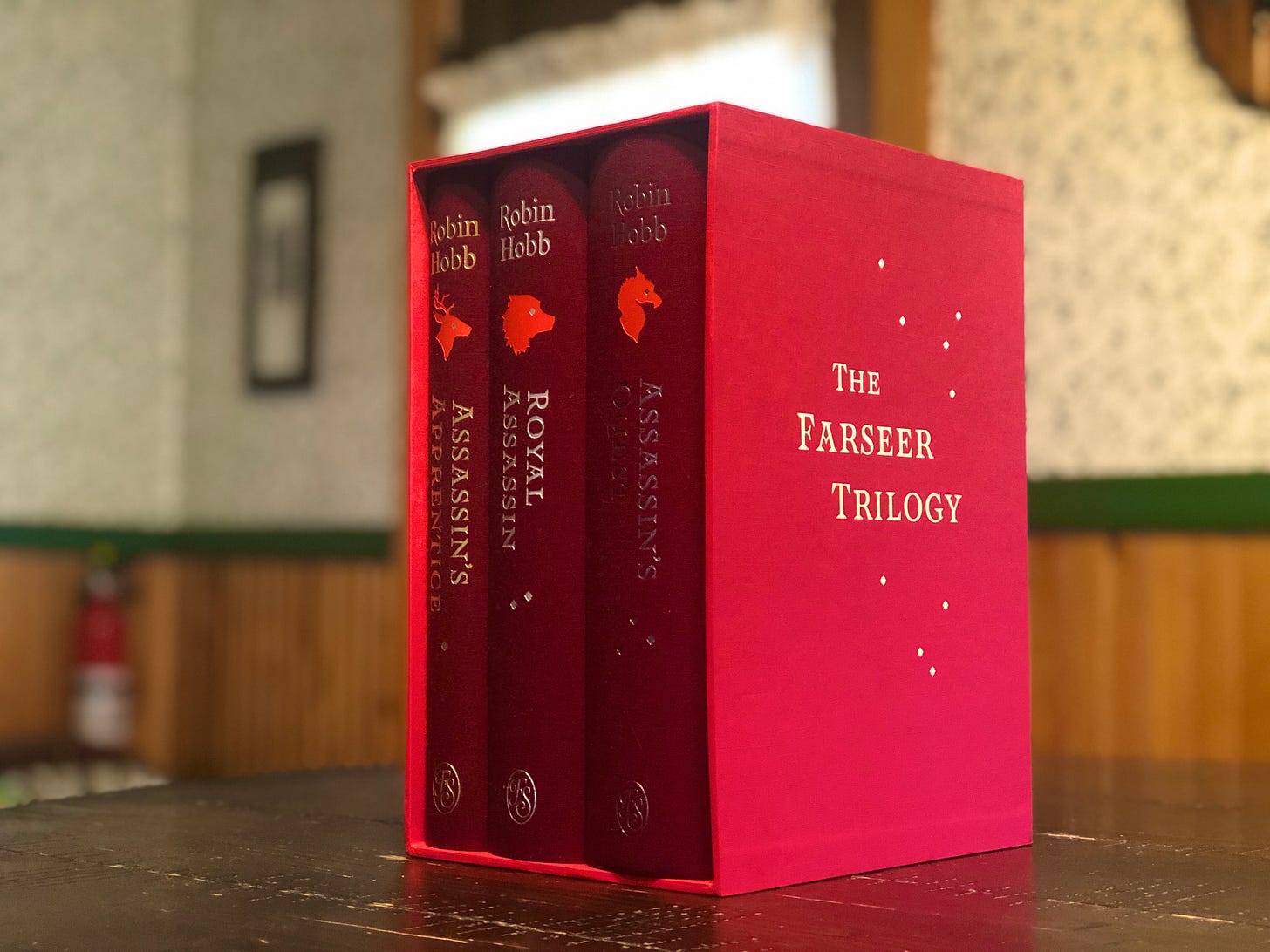

Last month, The Folio Society dropped a huge doorstop of a release: Robin Hobb’s Farseer trilogy, which includes Assassin’s Apprentice, Royal Assassin, and Assassin's Quest. They’re books that I haven’t personally dipped into, but they’ve come highly recommended from friends and writers who’ve raved about the series. The release comes on the 25th anniversary of the trilogy’s original publication. I spoke with Hobb about the book, looking back on that quarter century milestone.

Disclaimer: Folio Society provided me with an edition to review.

“It does reflect an earlier time in my writing life,” Hobb writes “but really, there is nothing I wish to change about it. It may sound egotistical, but Assassin’s Apprentice still works for me, both as a reader and as a writer. I’m still comfortable if I sit down and read a chapter or a few paragraphs from it.”

Following the relentless pace of science fiction and fantasy release schedules, it often feels like a promising fantasy debut might appear and vanish within months or even weeks as others overtake it. But I often see The Farseer trilogy recommended on lists when it comes to fantasy epics that people should check out. Hobb chalks this up to the first person tense that she uses for voice Fitz, putting the reader right in his place.

‘“I think it’s an intimate voice that draws readers into the story. It also allows the writer and the reader to share the characters thoughts, and to experience the world as the character does. In Assassin’s Apprentice and the books that follow it, sometimes the reader will realize that Fitz is not seeing things exactly as they are. He is a lens, but not always a perfectly clear one.”

In her introduction to the boxed set, Hobb speaks about two different modes of writing: “what if?” and “who is this character?” The latter leads authors to explore the ramifications of that question, leading to the story, while the former builds a story around the character as it guides the author.

I enjoy a character who is distinct. The character will not always make the obvious decision, or the decision that I would make. Will she walk into the room with guns blazing, hide behind the door to hear what people are saying, or walk away thinking it’s none of her business or too dangerous to interfere? A good character lets me experience the story as someone who is entirely different from me.

Ultimately, she notes that fantasy literature has certainly changed in the last quarter century: it’s “always been in a state of flux, one thing that I’ve always loved about fantasy and SF,” she writes. “I recall the wave of cyberpunk that washed through our genre, adding a new layer of flavor to it. Vampires had a strong decade or two, turning up in unlikely places. Alternate history! Romantic Fantasy. Books that are 800 pages long have replaced the 275 page paperbacks of my youth.”

Currently Reading

I mentioned finishing Ring Shout by P. Djèlí Clark above, and the other book that I’m closing in on finishing up is Gareth Powell’s Embers of War, which I’ve been alternating listening and reading between the audiobook and hard copy. It’s just what I’ve been needing: a fun space opera. There’s spaceships, ancient artifacts, AIs, and some cool characters. I’ve picked up the other two books in the trilogy — Fleet of Knives and Light of Impossible Stars — and I’ll likely be digging into them at some point in the nearish future.

In addition: I’m working my way through Paul Tremblay’s Survivor Song and Rebecca Roanhorse’s Black Sun, which I’m enjoying. as well as Alix E. Harrow’s The Once and Future Witches. Also on the to-read list is Tim Gregory’s Meteorite: How Stones from Outer Space Made Our World, which is a nice complement to Jo Marchant’s The Human Cosmos: Civilization and the Stars. I’m also working my way through K.R. Paul’s Pantheon.

At some point, Alix E. Harrow’s The Once and Future Witches will get on the list, and I’ve also recently picked up Peter Watts’ Blindsight, as well as Micaiah Johnson’s The Space Between Worlds, both of which have come highly recommended, and have been ones that I’ve been meaning to read. And of course, there’s the ever-growing long list that I’ve been meaning to get to. Sigh.

Further Reading

- 50 Scares for 50 states. The New York Times has a neat list: a horror novel for each state. I was pleasantly surprised to see that Shirley Jackson’s Haunting of Hill House didn’t make the list for Vermont. Not that there’s anything wrong with the book — it’s just that I’ve seen the comparison before.

- 100 best fantasy. Time assembled a panel of judges and worked up a list of 100 best fantasy novels of all time. There are some good ones on the list, but also some head scratchers. Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince? No Stephen King, as Katherine Arden pointed out. No Suzanne Clarke?! Really? N.K. Jemisin has a good essay in conjunction with it, though.

- Annalee Newitzletter. Annalee Newitz launched a newsletter of her own, The Hypothesis, and the first issue deals with Pompii, exploding brains, and more.

- Consequential SF. Over on Polygon, I listed out 15 SF novels that I felt were important and consequential to the genre in some specific ways, like climate change, the blending of literary genres, differing uses of pronouns and gender identities, and quite a bit more. Mind, this isn’t a “best” list: I was looking more for what I perceived as impact.

- Dystopia as Clickbait. Christopher Brown (who I recently interviewed!) muses about the growing use of “dystopian” as a descriptor for the current state of the world. “Flash forward to 2020, and the scenes on the news look more dystopian than the darkest new Hollywood futures streaming to our living rooms.”

- KSR interview. My friend Eliot Peper interviewed Kim Stanley Robinson about plausible utopias and his new book Ministry for the Future.

- New Battlestar. Over on Tor.com, I wrote about news that Simon Kinberg has signed on as a writer for a reboot of the Battlestar Galactica franchise. Universal has been trying to make this happen, but it’s been a slow process, something I’ll probably write a bit more about down the road.

- Robot and Crow. Annalee Newitz's story How Robot and Crow Saved East St. Louis is one of my favorite short stories of recent memory (go read it!), and now, there’s an audio adaptation!

- Shop Local. Over on The New York Times, Elizabeth A. Harris outlines how local bookstores are struggling this year. If you decide to buy any books that I recommend, please consider shopping at your local indie?

- State of Modern Fantasy. Over on Tor, I wrote up a panel that took place at New York Comic Con recently, featuring P. Djeli Clark, Jordan Ifueko, R.F. Kuang, Naomi Novik, and Ann and Jeff VanderMeer, in which they spoke about the modern state of fantasy literature vs. the classics. There are a lot of good takeaways from the panel, but most importantly were two things. One, a point made by Ifueko, about how classic fantasy is traditionally used to “reinforce the greatness of what was in place in that culture,” and two, noting that globalization has made it hard to package people up into neat categories.

That’s all for this week. As always, thank you very much for reading: I always appreciate it. Let me know in the comments (or via email) what you’ve been reading and enjoying!

Andrew