This year's awards scuffle and influence in the SF/F world

Is this thing on?

This issue is very delayed, and I’m very sorry about that. I’ve been crawling out of a pit of sickness the last couple of weeks. Two weeks ago, my son, wife, and I all came down with what we think is the flu, which wasn’t fun at all, and knocked us out for most of the first week. Right after that, I came down with a sinus infection, which gave me a fever and plugged my head up for another week. It’s exhausting when you can’t breathe normally, and I just haven't been able to get to writing much of anything outside of work.

Fortunately, I'm better now, and digging out from under a pile of stuff. As a result, this letter is going to be a bit longer, because I’ve got a bunch of things that I’ve been jotting down that I’m only now getting around to writing up.

One programming note: this newsletter isn't really a good avenue for pitching me on stuff. I'll put together a page on my site about how to do that, but, the tl;dr version is that it's not by replying to this, please.

Obit: Betty Ballantine

Last month, publisher and editor Betty Ballantine died at the age of 99. She's a major figure that you might not have heard about in SF/F circles, but the market that we know today likely wouldn't exist as it does without her.

At the beginning of World War II, the paperback as we know it really didn't exist. Science fiction stories came out in pulp magazines, and what books were out there were generally pretty expensive hardcovers. There had been paperback books during the post-Civil War era, like dime thrillers, but as Al Silverman noted in his book The Time of Their Lives: The Golden Age of Great American Publishers, Their Editors and Authors “when business flopped throughout the country, paperbacks mostly disappeared—until the 1930s."

There were a bunch of technological innovations at the time to print cheaper books, but most people weren't buying books during the Great Depression. World War II helped change that — there were big pushes to get books to soldiers, and when they returned, there was a huge economic boom that meant people had more discretionary income to buy — among other things — books.

It's in this environment that English publisher Allen Lane hired Ian Ballantine to produce a line of paperbacks in the United States. Lane is known for those iconic Penguin paperbacks — the orange and white ones — which were extremely cheap. Ballantine didn't last long there, but he went on to start his own imprint, along with his wife, Betty — Bantam Books, and later, Ballantine Books. They did some interesting things, like releasing hardcover and paperback editions at the same time, and became known for publishing books like Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451.

As the NYT points out, Betty was an influential figure here — she knew the field, and brought a lot of those writers who had been working in the short fiction market over to books. Without her, the genre marketplace would look very different.

Hugo Award Nominations

Nominations for the Hugo Awards are due this week (Saturday), and I’m working on rounding up what I’ll put down for my nominees. Looking over what I read, here’s what stood out for me:

- Novels: Semiosis by Sue Burke, The Gone World by Tom Sweterlitsch, Space Opera by Catherynne M. Valente, Trail of Lightning by Rebecca Roanhorse, The Calculating Stars / Fated Sky, by Mary Robinette Kowal, Ball Lightning by Liu Cixin, Record of a Spaceborn Few by Becky Chambers, and Foundryside by Robert Jackson Bennett.

- Novellas: Gods, Monsters, and the Lucky Peach by Kelly Robson, Time Was by Ian McDonald, Artificial Condition / Rogue Protocol / Exit Strategy by Martha Wells, The Black God's Drums by P. Djèlí Clark, War Cry by Brian McClellan, The Freeze-Frame Revolution by Peter Watts, and Armored Saint / The Queen of Crows by Myke Cole.

- Novelettes: The Only Harmless Great Thing by Brooke Bolander, Wings of Earth, by Jiang Bo, Farewell, Doraemon, by A Que, and Okay, Glory, by Elizabeth Bear.

- Short Stories: Without Exile by Eleanna Castroianni, What Gentle Women Dare, by Kelly Robsen, The Tale of Three Beautiful Raptor Sisters and the Prince Who Was Made of Meat, by Brooke Bolander, The James Machine, by Kate Osias, The Phobos Experience by Mary Robinette Kowal, To Fly Like A Fallen Angel, by Qi Yue, The Minnesota Diet, by Charlie Jane Anders, Sparrow, by Yilin Wang, and When Robot and Crow Saved East St. Louis by Annalee Newitz.

- Related: Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke, and the Making of a Masterpiece by Michael Benson, Astounding: John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction by Alec Nevala-Lee, Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth by Catherine McIlwaine, and Anything You Can Imagine: Peter Jackson and the Making of Middle-earth by Ian Nathan. I suspect Strategy Strikes Back: How Star Wars Explains Modern Military Conflict by Max Brooks/John Amble, M.L. Cavanaugh, and Jaym Gates will fall under this category as well.

There's probably a couple of others in other categories that I'm missing. I would be remiss if I didn't also say that I'm eligible for Best Fan Writer? (I think?) Better Worlds came out in 2019, so it's not eligible at all (but keep it in mind for next year!)

tl;dr: there were a lot of really good stories published last year! I’ll probably have to pare these lists down a bit, and even if you’re not a nominator, I’d highly recommend checking these out. The Nebula nominees are already out, and I think that there’ll be some carryover from one list to the other.

This year’s award scuffle & Influence

It seems like every year, there's some argument about awards. This year's seems to be about the Nebula Awards.

SFWA recently released a statement about the 2018 Nebula ballot:

In light of recent events regarding the 2018 SFWA Nebula Nominations short list, the SFWA Board is aware of the ongoing issues. We will continue discussion on ways to improve our processes so that something of this nature does not happen again. With that said, we would like to make it clear that the organization frowns on any attempt to manipulate our Nebula Awards nomination and final ballot processes which includes logrolling and slate campaigns.

The issue seems to have surfaced because of a popular self-publishing Facebook group for indie writers called 20BooksTo50K. It describes itself as a “safe place to discuss ethically how to make more money as an author,” and boasts nearly 30,000 members. Ahead of the Nebulas, the group published a recommended reading list to try and draw attention to self-published works for the Nebula list. While described as “not a slate” (think back to the block-voting from the Sad / Rabid Puppies a couple of years ago), it’s… kind of a slate. A couple of these stories ended up on the Nebula list on the Nebula / Novelette / Short Story sections, which has dredged up a bigger argument about how awards are handled.

What's deal with this? In a nutshell, authors taking a chance to break out of the crowded market and have books and stories that they're invested in put before a much larger audience, with the potential of new sales / attention put towards those works.

Part of the story here is that the Nebulas and Hugos are big awards, and nominations lend themselves a certain amount of legitimacy to works that make the list. Publishing is hard, and every little thing helps, from reviews in big publications to hitting the top spot on a bestseller list (doesn't matter which one).

As a result, these sorts of awards are a big target for groups looking to either get sales or some sort of confirmation that they're doing the right thing, whether that's self-publishing, some smaller subgenre, different medium, etc. "Hugo/Nebula Award Winner" or "Hugo/NebulaNominee" is a good thing to slap onto a cover, sales-wise. Linda Nagata's self-published novel The Red was the first self-published novel to get a Nebula nod, and it opened the door to a three-book deal for the rest of the trilogy at Saga.

There's the egalitarian view of this: the best works rise to the top, and then there's the tactics behind the scenes that help make that happen. Publishers, big, small, and independent will work to make sure the right readers read these stories. Big publishers like Tor Books have a marketing budget to make that happen. It's no coincidence that you'll see a publisher put a lot of resources behind a book (think Jenn Lyon's Ruin of Kings, which came with a 20-chapter marketing rollout, or free copies of a big title like Scalzi's The Collapsing Empire). You'll see publishers give away copies of books or making the authors available to to a wider swath of reviewers, booksellers, and vocal readers, because that noise translates into more awareness for the title when the on-sale date comes. I don't think that's necessarily a bad thing — it's effective advertising — but that marketing budget is something that comes with scale and lots of resources.

When it comes to the self-publishing market, I don't see as much of that, simply because it seems to be more decentralized, and marketing advice for authors can be iffy and contradictory. Some authors will hire PR firms or specialists, or build established relationships, and build out a release plan. Others will just release their book with no notice, hoping that it will capture the attention of readers. Still others will work to game the system, using groups to drive up ratings or purchases, in the hopes that that will bump the title up a bestseller list, and thus, get more attention. Scientologists are thought to have done this with L. Ron Hubbard's books, and more recently, a book called Handbook for Mortals. This goes beyond advertising, and it's pretty deceptive for consumers and publications.

A similar thing seems to have happened with the Nebulas — a popular group was able to drive enough votes to influence the outcome. Is that good? Potentially for the authors, but there's a high risk of backlash when it comes to award voters — the last couple of years, all attempts at slated voting have been met with "No Award," and rules to blunt their impact. But other awards, like the Dragon (essentially set up as the anti-Hugo), or Goodreads Awards welcomes the general public, and their low-barrier-to-voting makes it easier for groups to push for influence there. (SFWA is in a slightly different category, because it’s made up of professional writers who have certain entry requirements.)

Because of their longer legacies, the Hugos / Nebulas are one of those rare sorts of consensus awards for large swaths of fandom. But they've struggled with the changes that the internet is bringing with it. My guess is that we'll see more groups like 20BooksTo50K pop up with significant numbers, and which will throw their weight around, especially with awards, lists, and coverage where it's easiest. In my experience as a reviewer, I've seen some of this first-hand: fans of an author with significant followings tweeting or e-mailing their displeasure at their absence in a list (or recommending that I add them to a list), or boosting the signal on a story I've written. (The former is usually what happens, however.) These boosters, either organized, or on their own, can certainly shape opinion if they're loud enough — acting as PR in ways like what major publishers do through established channels. I don't know that it's as effective as professional PR, at least when it comes to hype, but it is there.

The problem that I see there is that hype is hype — it doesn't always equate to quality. That's why the Sad / Rabid Puppies campaigns didn't go beyond "No Award", because voters recognized what was happening — the books weren't there because of the quality, they were there because of a campaign to put them there. I spoke with Marko Kloos recently, and in our post-interview conversation, he told me that he withdrew his nomination for his novel when he learned that it was part of a slate.

There has been a lot of commentary from all sides about how this is a war of old-verses-new, but I don't really think that that's the case. I think it's more that established institutions like SFWA and the Hugo Awards simply aren't equipped to handle some of the rapid changes that we're seeing in the publishing industry and how fandom organizes itself, with the help of platforms like Facebook or Twitter. I think it's also less "old man yells at cloud," and more not recognizing potential issues or reacting quickly before they become a problem. The traditional "Fan" community doesn't really turn and adapt quickly.

That's a problem, because SF/F has changed extensively over the years — I've met people who are still grumpy about Star Wars introducing an entire generation to science fiction, rather than Dune or Foundation. Traditional Fandom as a model that doesn’t really scale up well, especially in a world where you have so many platforms and properties. Fandom arose as its own group — people who read the same magazines and novels — and as science fiction and fantasy has become more mainstream, we've seen more groups. You have Star Wars and Star Trek fans, fans for D&D and Dragonlance, and so many others. You have groups that advocate for authors of color or for works from queer authors. Meanwhile, you're also seeing other places, like Slate, The Verge, Nature, Wired, and other publications spinning up their own fiction, bringing in new audiences that aren't really part of traditional Fandom. There's certainly crossover in all these groups, but it's easy to see that "Fandom" isn't really a be-all-and-end-all category.

I see this more as a sort of arms race to figure out how to get the most attention as all of these groups figure out how to work with one another. My guess is that we'll see the self-published world become more sophisticated over time, at least authors who recognize that it's a business, rather than a passion project. There are advantages for competent authors — you might have a bit more control over your IP rights (platform dependent, obviously), and you might not have to wait for over a year to get a book out after you've finished it. (Check out Linda Nagata's blog for some insight here.) Part of the struggle here is getting an established group of readers to adhere to works that come from outside of the publishers they're used to, and that's led to this sort of line-cutting in the last couple of years. I don't think it's an issue that will go away anytime soon, but as organizations make their rules a bit more resilient, they should also make sure that they're paying attention to and recognizing the non-traditional works that will continue to crop up.

Further Reading

I want to plug a book that I recently picked up — K. Chess’s debut novel, Famous Men Who Never Lived, which I reviewed for The Verge last week. Of all the books I’ve read this year, this is probably one of my favorites. It book follows Hel, a woman from an alternate time, one of 156,000 refugees who flees her world when a nuclear attack devastates everything she knew. She left everything behind — her job, almost all of her belongings, and her child.

In our world, she ends up lost and treading water. She and the other refugees are in a familiar-but-unfamiliar world, where they deal with a new strain of xenophobia and hostility: people don’t trust them, they fear them, and they hate them. Along the way, she hooks up with a fellow refugee, who brought along a paperback copy of a science fiction novel, The Pyronauts. Hel soon has a purpose: put together a museum that commemorates their stories, in the house where the book’s author lived. But, when the book goes missing, she goes to some pretty desperate lengths to try and find it.

This is a really stunning read. It’s multi-layered and reminded me quite a bit of the best stories that Philip K. Dick produced in his lifetime. Chess doesn’t fixate on the fiddly bits of alternate realities — she could have spent quite a bit more time going over the differences between the worlds, but keeps the action squarely focused on the characters and their plights. It’s a good example of where a more literary-styled story really succeeds, recognizing that the speculative elements are there to support a story changes the story itself — rather than just slapping a robot or plague into what’s effectively a non-speculative story. I highly recommend this one.

Another book I read recently was one that I was looking forward to — only to be really disappointed by it: The Lady from the Black Lagoon: Hollywood Monsters and the Lost Legacy of Milicent Patrick by Mallory O’Meara. The book ticks off a number of things that I find really appealing: a biography of a lost Hollywood personality, a woman whose career was cut short by men who were jealous of her work, and a scathing look at how things really haven’t changed for women in the entertainment industry. The book has all of that, and there are some really interesting things that O’Meara writes about.

The problem that I had was that O’Meara also spends a considerable amount of time writing in the book how she wrote the book which is… less interesting. There are huge, long sections where she’s talking about her joy at discovering something in an archive, makes some connection or meets someone. That’s all fine and good, but it leaves a very scattered narrative that she can’t seem to extract herself from. The AV Club published its own review that largely mirrors my thoughts on the book. I sort of think that O’Meara might not have found as much about Patrick’s life, and had to pad the book out a bit. Which is fine — but this book is largely structured around her discovery of the various elements of Patrick’s life, which muddles the larger story.

Something that bothered me a bit (speaking as someone who has studied and written extensively about history) is that O’Meara doesn’t really place any emotional distance between herself and her subject. She draws a number of valid parallels between herself and Patrick, which works until it doesn’t. There are a number of points where she fills in blanks for what Patrick might have been thinking, and that strikes me as a bad way to do history, because one observer’s experiences don’t necessarily equate to that of their subject. It might be correct, but it also might not be: there’s not really any information that pushes it in either direction, and while a gut feeling might lead you in that direction, that’s not really a good way to convey information in a factual text.

As a historian, I wanted this to be a far more rigorous study of the woman’s life, which in turn would have strengthened the message that O’Meara is trying to convey: Hollywood is brutally toxic for women, and it has been for a very, very long time. It’s a shame, because O’Meara’s enthusiasm for Patrick is infectious, and ultimately, this just felt like it didn’t keep a sharp focus on its story. But, I think that it's good that there's attention placed on this particular subject, and it's a very timely book, despite my misgivings.

When it comes to film histories, I finally finished Anything You Can Imagine: Peter Jackson and the Making of Middle-earth by Ian Nathan, an exhaustive history of Peter Jackson’s Middle-earth franchise. I grew up loving Tolkien’s books (I’ve talked about this quite a bit before) and the films were a revelation as to what you could do with film and bring a work as complicated as Tolkien’s to the screen. That’s no easy feat, and reading Nathan’s book shows just how close we came many, many times to getting films that would have really mangled the books.

What strikes me about Jackson’s LOTR trilogy is that he, Fran Walsh, and Phillipa Boyens understood just what was so special about Tolkien's story and world: they contain a depth rarely seen in fiction, and that's one reason why the books have endured. This really prefigures a lot of what we’re seeing in cinema / TV now: long-form television is expanding what we can do with adaptations, and LOTR certainly set the mold for shows like Game of Thrones in many ways. They're stories set in this really big worlds, which audiences can really sink into and obsess over.

Nathan’s book is less interesting when he finishes covering the first trilogy — the last hundred or so pages of the book covers the post-release drama, from Jackson’s lawsuit to the work to build The Hobbit, but it feels like it really should have been an entirely separate volume, rather than something that was tacked on afterwards. I’d recommend watching Lindsay Ellis’ three-part video series about franchise if you want something a little more critical.

Finally, a couple of shorter stories: One I read recently is Kevin Bankston’s short, “Early Adopter,” which appeared in February on Motherboard. Another one that I’m looking forward to reading is True Blue, by Eliot Peper, illustrated by Phoebe Morris, and designed by Peter Nowell. It looks pretty interesting, and a neat example of blending web design and storytelling.

And finally — The Wall Street Journal has taken notice of this "optimistic" fiction trend, and name checks Better Worlds. Give it a read.

Reading List

I’ve got a couple of books that I’ve been reading. The first is Kameron Hurley’s upcoming novel (comes out next week) The Light Brigade. It’s good, and I’ll agree with some of the comparisons to Starship Troopers and The Forever War, but I need to finish it first. Look for a review next week, if all goes well.

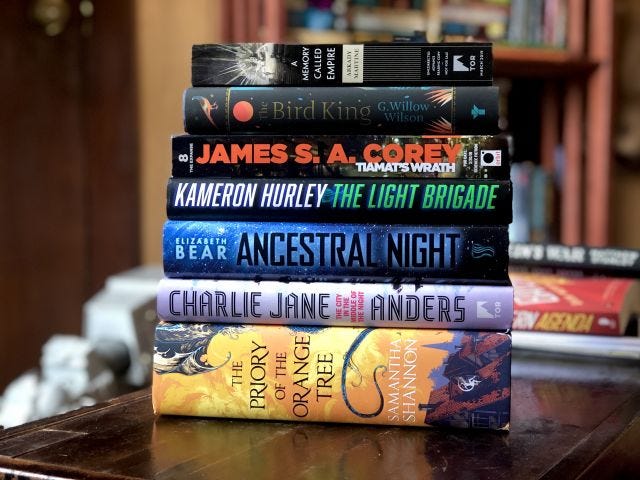

I’ve also got G. Willow Wilson’s novel The Bird King on my to-read list, as well as Elizabeth Bear’s Ancestral Night, and Charlie Jane Anders’ The City in the Middle of the Night. I also have the new Expanse novel, Tiamat’s Wrath by James S.A. Corey, The Priory of the Orange Tree by Samantha Shannon, and Arkady Martine’s debut, A Memory Called Empire. I’ve set aside Marlon James’ Black Leopard, Red Wolf, because it’s such a slow read for me. I’ve liked it and plan to keep picking away at it, but I have other things I need to move forward on.

After that, there's April's crop of books — Rebecca Roanhorse has a new book, Storm of Locus, while Chen Quifang has his debut translation out, Waste Tide, both of which are high on my to-read list. I also need to make some time to read some non-SF/F stuff, too.

That's all for now — this was a bit longer than I thought it would be. I should be back on schedule — checks notes — for the next issue this Saturday. If you liked this, please consider forwarding it on to a friend or someone you think will be interested, or tell folks on your favorite internet platform. As always, please let me know what you think!

Best,

Andrew