Three Novels About Unbalanced Worlds

Robert Jackson Bennett's Shorefall, Octavia Butler's Parable of the Sower, and Mary Robinette Kowal's The Relentless Moon show off worlds that are full of imbalance

This past weekend was supposed to be San Diego Comic-Con, but the ongoing coronavirus pandemic meant that this year’s event was virtual. It’s definitely not the same. There’s certainly plenty of reveals and trailers and things that are keeping me employed, but I’m missing being on the con floor, especially in a year when there really aren’t any conventions. On top of that, it’s been a while since I’ve gone to SDCC: I didn’t go last year because work priorities and time off requests getting jerked around, although I did get out to a bunch of conventions last summer/fall. I love taking in the vibe of the crowd, and the general enthusiasm level for everything that you see on display there.

Mind, I wouldn’t actually go to a convention this year, not with COVID-19 raging along across the US. A convention now seems like it would be an explosive biological event that makes the crisis even worse. They’re just not conducive of the things that you need to get this under control: masks, social distancing, clean spaces. “Con Flu” was already a widely complained about thing after a major event — the result of so many people coming into contact with one or two sick people. A convention has to be an epidemiologist’s worst nightmare. So, I’ll just scroll through old pictures of past events, and hope that we’ll get back to that sort of event someday.

Whenever conventions do open, it won’t be the same: we’ll certainly see more people wearing masks, more signs and restrictions warning people to keep their distance. They’ll likely get more expensive because of higher insurance prices, and with smaller head counts. I imagine that a number of the long-running traditional conventions will quietly end, not to mention many of the smaller conventions that you see pop up all over the place. We’ll see.

I’ve been reading a lot recently — social isolation is good for that — and I’ve got a trio of books that I had some thoughts on: Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, Robert Jackson Bennett’s Shorefall, and Mary Robinette Kowal’s The Relentless Moon.

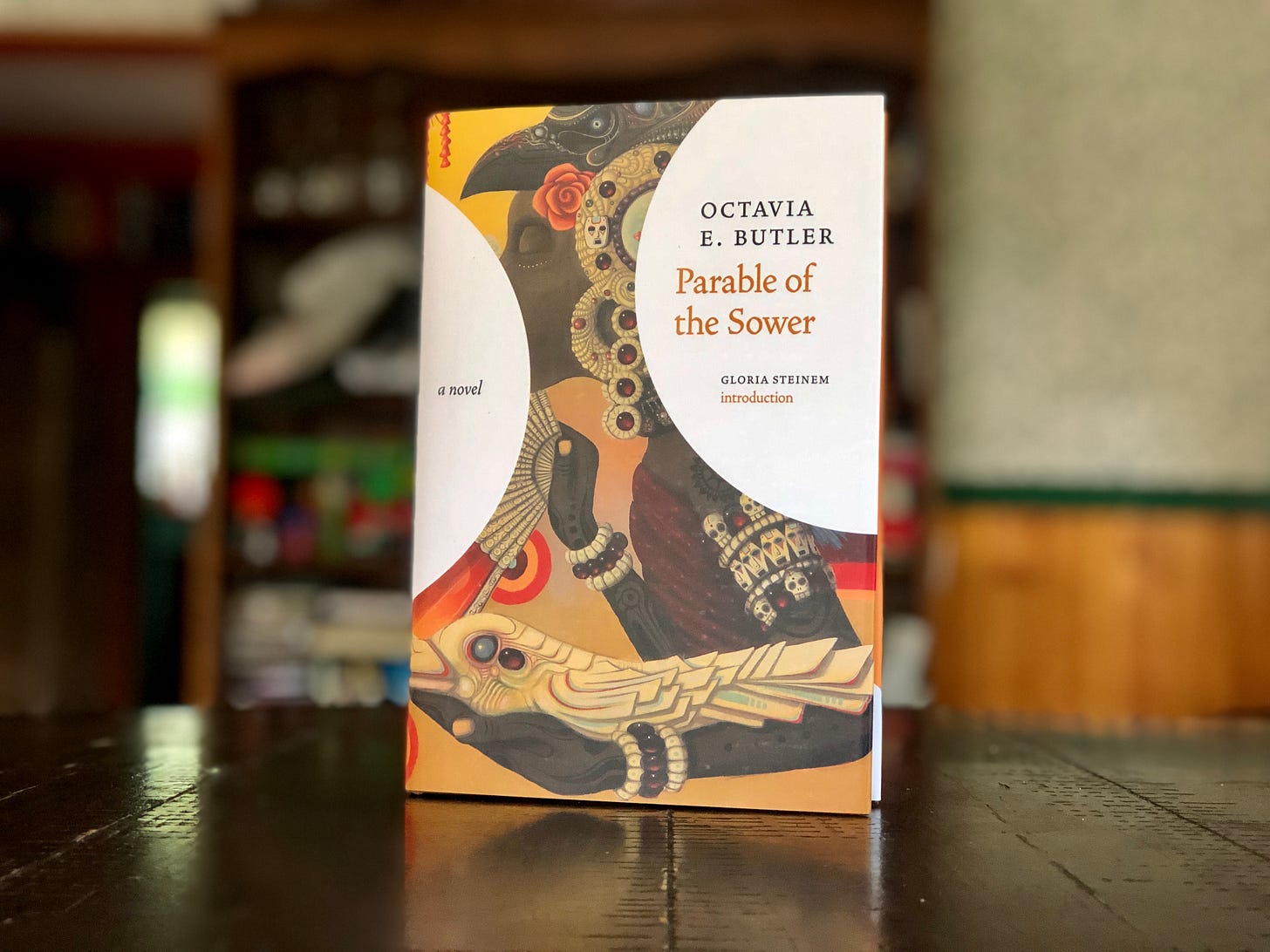

Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower

There are some books that you dig into because they’re ubiquitous: it’s hard to escape the influence of books bearing the name Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, or Robert Heinlein. They’re the welcome mat for the genre, books that are easy to get into and understand as a teenager.

There are others that are influential, but I haven’t picked up until now — ones that I’m glad that I’ve waited, because I feel like I wouldn’t have really understood what the author was getting at with it. I had this thought as I was reading Octavia Butler’s novel Parable of the Sower in my backyard the other day, and while listening to it while helping my brother strip a porch of its paint.

Butler’s novel follows the journey of a young woman named Lauren Olamina, who grows up in a gated community that shields her and her family from a slowly collapsing US. They have little money, there’s horrific crime out beyond the front gates, and a major corporation is experimenting with its own closed communities: a new version of a company town where you work and live for the company.

Lauren is afflicted with a particular condition: hyperempathy, in that she can feel the pain of others around her. The gates to her home are eventually breached, and she’s forced to trek north to possible safety, gathering people to her side as she begins to create her own philosophy of existence, Earthseed. This is a book that’s chillingly real, from a California that’s burning up, to the occasional mention of a crewed Mars mission to the proliferation of guns.

I’m glad that I waited until this particular moment in 2020 to pick up the novel, because I’m not sure that I would have fully comprehended it: how she viewed race through the lens of an apocalyptic collapse and the rise of corporate influence.

Some of that is a failure of imagination on my part: had I read this in high school or a decade ago, I would have likely just seen it as book about a girl going on a hike in the midst of an apocalypse. But given the last decade — where society at large (or at least those who haven’t had to endure these problems already) has begun to better learn or understand the complexities of race, power, privilege, white supremacy, and corporate greed and malice. Reading this book for the first time this summer was enriching and enlightening.

But the biggest thing that I drew from the novel comes down to Lauren’s abilities and the importance of empathy. She muses at one point what the world might look like if everyone had her condition, and after enduring the last couple of years of social media, online harassment campaigns, or even the comment sections on Facebook pages, I’m understanding what Butler was really getting at: the world is destroying itself because people lack this ability, because they can’t understand one another, or realize that the only way out of disaster is with people by your side.

Then again, if I’d read it earlier, maybe I would have better understood the world long before we reached today.

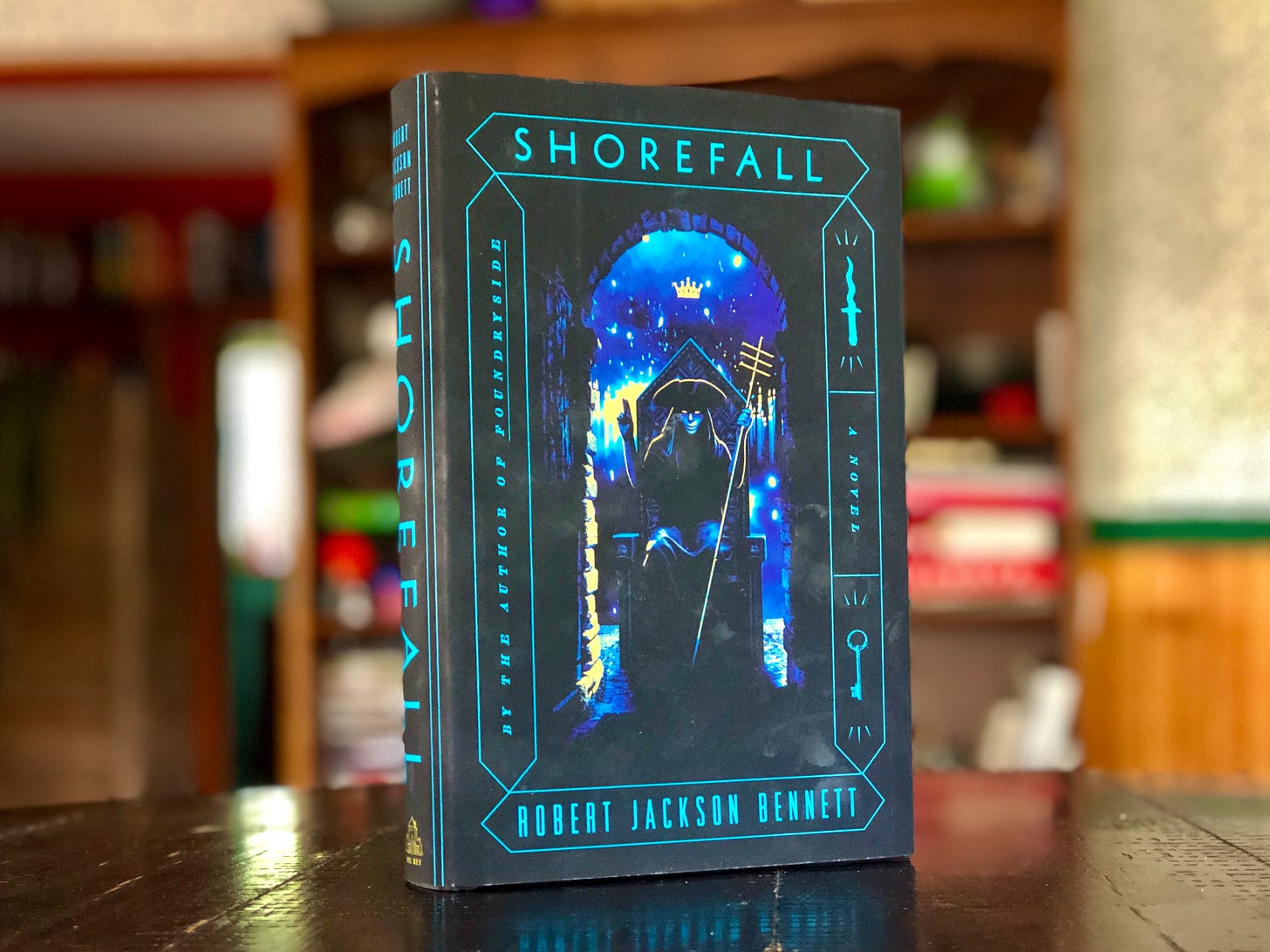

Robert Jackson Bennett’s Shorefall

Two years ago, I picked up Robert Jackson Bennett’s Foundryside, and was blown away by his depiction of magic. In my review, I wrote about the book as a cyberpunk-like novel, about a young thief who picks up a magical key and gets pulled into a conspiracy on the part of some shady people to reprogram reality.

Bennett approaches magic like it’s a technology: it’s a force that permeates the world, and with the right arguments, you can convince an object to do something that it might not do. Say for example, you want to secure a door. Here in the real world, you might put a lock on it, with a key that allows you (or anyone with it) access. In Bennett’s world, you enchant — scrive — the door, and it knows that it can only open the door under certain circumstances: someone puts the right key in the lock, or it’s enchanted to recognize a specific person or heartbeat, or something like that. To get in, you need the right person or key, or in Sancia Grado’s case, you have the ability to talk directly to the enchanted door, and convince it that it’s not breaking its programming if it would only open in the other direction.

Her particular set of abilities here made her an ideal thief, and we learned in Foundryside that she was a former slave who had been augmented with a scrived plate that gives her this ability. After discovering a key named Clef, she stumbles upon a plot from some a very shady person that want to use Clef to rewrite reality to suit their needs by transforming themselves into a god.

Shorefall takes place a couple of years later, and Sancia and her friends have been working to remake the world in their own ways: they’ve been trying to dismantle the established merchant houses that have an iron-clad grip on her world’s economy, which leads to slums, slavery, and oppression. This work comes to a screeching halt when a character named Valeria reaches out to Sancia with a message: her creator, an ancient hierophant named Crasedes Magnus — a godlike character that had destroyed entire civilizations over his reign — has somehow returned to life, and he’s aiming to remake humanity.

There’s a lot going on in these two books, but one thing really jumped out at me: power corrupts, even when someone has the best of intentions. Much of the novel covers Sancia and her allies working to figure out the threat to the world, working out how to address it, and then trying to prevent the worst case scenario.

There’s plenty of fantastic horror here: Sancia and company trying to stop Crasedes Magnus from entering the city of Tavanne, only to discover that he’s figured out how to not only return to life as a living god (there are some real Lovecraftian elements to him here), but he’s pretty much put together a bullet-proof plan to enact his plan: essentially reprogram humanity, stripping people of free will. Over his millennias-long life, he’s seen humanity rise and fall a couple of times, and he’s realized that our inherent ability to improvise and innovate are traits that are inevitably weaponized, leading to war, concentrations of wealth, and slavery. Remove that ability, and humanity would exist peacefully. Earlier, he created Valeria as a tool to help with this process: designing her to eventually reprogram humanity before she rebelled and snuffed him out.

There’s elements of Crasedes Magnus’s plan that feels very much like something out of a supervillan playbook: have grievance with the world, create master plan, profit??? And while that borders a bit on the cliche side of things, Bennett does a masterful job of playing up Crasedes Magnus as a horrifying and yet sympathetic character. We learn that he has a deep relationship with Clef, and that their own personal origin story sets up his motivations in a fairly logical manner. The thing here is — and this is where the best villains are made — he’s not entirely wrong about what he wants to accomplish. Technology certainly leads to inequality (just look around at the present state of the world or hell, even the 20th century) and oppression around the world, and there are points where drastic action is required to enact change.

We see both sides of the coin here: Sancia and friends getting information from a would-be ally who’s trying to dismantle the system that led to their respective enslavements, and Crasedes Magnus, who might have understandable motivations, but who has become so corrupted by his own power that any system that he puts into place will be just as bad as what he’s trying to replace — or worse. It’s a solid setup for the final installment of the series, and I’ll be interested in seeing how this ends up.

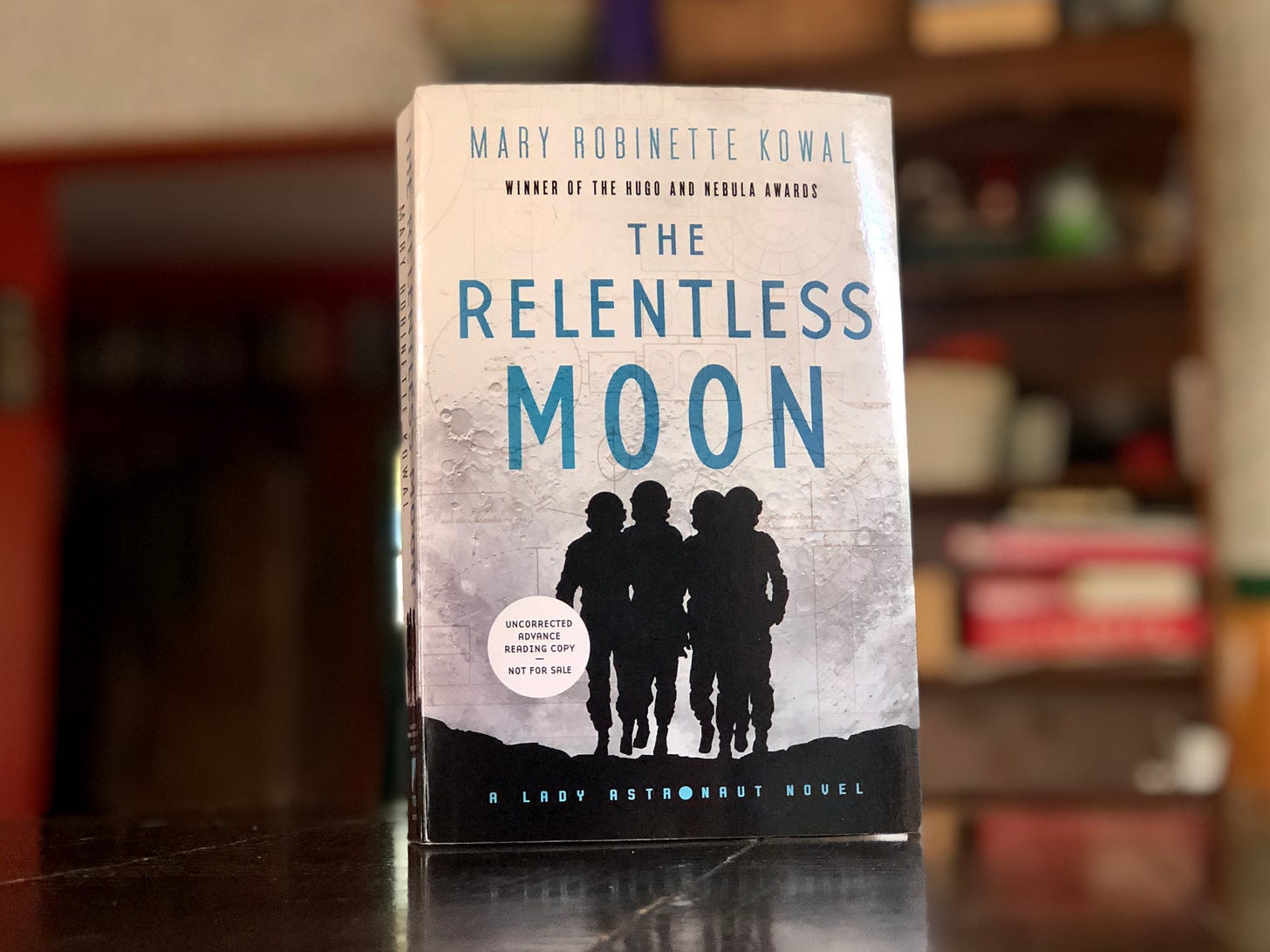

Mary Robinette Kowal’s The Relentless Moon

The history of space is inherently one of exclusion. Mary Robinette Kowal has been writing about this recently for places like The New York Times, pointing out that the snafu with space suits that sidelined the planned all-female spacewalk isn’t just a budgetary thing with NASA, it’s that space is inherently designed for male astronauts, and that because women weren’t included in the US space program until Sally Ride went up in the 1980s, it’s had an impact that ripples out to the present day.

Read my interview with Kowal here.

That focus on inclusivity is something that runs under the hood with her Lady Astronaut series, an alternate history where humanity must figure out how to get into space before the Earth overheats after a massive asteroid impact in the 1950s. In the first two installments (and assorted short stories), we watch as a handful of women and astronauts of color fight to join the program, because what good is a space program designed to lead to permanent habitation if you only send up a select group of people?

In The Relentless Moon, Kowal shifts focus a bit. We follow Nicole Wargin, one of Elma York’s fellow “Lady Astronauts”, who’s dealing both with her standing in the space program and her husband’s impending presidential election. While the International Aeronautics Coalition is working to further build its foothold in space, attitudes toward the space program have begun to sour: some people have begun to question the validity of the science underlining the IAC and need to move off-planet, others are rightfully protesting the resources that are being taken away from people in desperate need, and yet others are motivated by religious concerns. Riots have begun across the United States, and a terrorist cell appears to be working to infiltrate the IAC, with the intention of destroying its efforts, or at the very least, sowing doubt into the future of the program.

Wargin is sent back into space to the growing lunar colony, where she’s tasked with working to help flush out the plot against the IAC. Immediately, a whole new set of problems arise. The rocket that brings her up to the Moon experiences a rough landing, breaking her arm and causing a serious fuel spill that causes numerous problems for the base. A BusyBee (think the lunar craft from 2001: A Space Odyssey, but for one or two people), goes missing, there are power outages, and signs of deliberate sabotage.

If there’s any one thing that’s underpinning Kowal’s work with this series, it’s her spotlight on the systematic issues that exclude people from various parts of the world. But what I appreciate the most about this series is her approach to this particular observation. The Lady Astronaut novels are hard science fiction that don’t ignore the systemic problems running under the hood. It’s a particularly clear-eyed and principled view of the world, recognizing both the things that excite and delight about science fiction, while also pointing out that there are major issues thrown in the way of people.

The Relentless Moon picks up that mission from the prior two books and keeps running it forward. Kowal weaves together a solid thriller as Wargin works to figure out the identity of the saboteur, as well as an empathetic character story as she deals with being apart from her husband, a debilitating eating disorder, and your run-of-the-mill sexism that leeches into every part of the space program. Neither plays a backseat role to the other: both are important to the world that we see, and Kowal’s portrayal here feels raw and honest, a portrait of a complicated character that is driven, principled, and utterly human.

That’s an important thing, I think. 2019 marked the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 landing, and in the years since the space race was in full swing, NASA consciously placed those astronauts on a pedestal. They were heroes (rightfully so) who became more than just men (and later women). But they were also deeply human, and looking at the history of spaceflight, you can see those moments when they bucked NASA’s direction and image: John Young brought a corned-beef sandwich with him on Gemini 3; members of the Apollo 15 crew brought along some stamps to the Moon to sell when they got home; and the crew of Skylab 4 turned off their radio and refused to work for a day after they were overscheduled. Couple that history with science fiction’s propensity for supermen, and you have a recipe for characters that aren’t quite believable or realistic, despite the widely-held intention of hard SF to rigorously depict realistic science and characters.

Kowal doesn’t sacrifice realism for human drama, and vice versa: The Relentless Moon is a raw, honest depiction of the challenges of spaceflight and solar system habitation. It’s simultaneously aspirational and optimistic for what the space race might have been, and steeped with a keen understanding of human nature and the problems that we bring with us.

All three of these novels share one thing in common: they recognize that the world is unbalanced in some way: whether that’s economics or the treatment of women and people of color. In each instance, Bennett, Butler, and Kowal each depict worlds that could easily be like our own, strip away the present moment (although for Butler, that book’ fast approaching the mid-2020s depicted), and layer on an element of speculative changes, whether it’s the collapse of the US, a fantastical and magical world, or another take on the state of the space race.

Ultimately, each novel does what great science fiction is supposed to do: explore the nature of the world around us, both by putting forward a set of incredible characters that you root for as they face insurmountable troubles, and by pointing out a central problem of the world for you, the reader, to recognize and internalize as you go about your every day lives.

As always, thanks for reading. Let me know which of these three books speaks to you the most — they’re a varied bunch, but not in quality, and I enjoyed each of them very much.

Next up: I’ve got a roundup of the books coming out in August coming this for all subscribers on August 1st, so stay tuned for that on Friday. There’s a good batch of books coming.

For paid subscribers, I’m aiming to send out two things. The first is some thoughts about the space race sparked by Apple’s upcoming second season of For All Mankind — the trailer for it just dropped at San Diego Comic-Con. That should go out to folks later today. I’ve also been working on the audio for the Mary Robinette’s interview, which I just need to put the finishing touches on — I’ll send that out later this week if all goes well. If you’re interested in getting those, you can subscribe here.

Have a good week!

Andrew