Writing the Future of War

This past week has been a busy one. Not just because of last week’s Hugo Awards ceremony — huge thanks to those who followed along with my live-tweeting of the ceremony, and for finding your way here — but I’ve also been doing some decidedly non-SF/F work, in the form of helping my brother paint a house, something I’ve never done before.

This newsletter picked up a bunch of new subscribers, so a bit of an introduction is in order. This letter is one of the regular free posts that I put together that I call a roundup: they feature a couple of shorter reviews or commentaries on recent things, a roundup of books that I’ve been reading (or wanting to read), and of recent articles that fall into this intersection of science fiction / fantasy / technology / reading / etc. Welcome!

My reaction to the Hugo Awards ceremony definitely attracted the most attention of anything I’ve written on this newsletter, and it garnered some mentions from places like The Sun, Vulture, Yahoo! Entertainment and The Washington Post.

Yesterday, I wrote about the 75th anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing, and how it relates to the science fiction genre. You can read that here. That post was originally supposed to be a paid letter, but I figured that it was worth sending out to everyone, given that today’s anniversary. If you liked it, please consider subscribing — subscriber support helps make those in-depth posts happen!

In line with that, I’m going to shift focus from the Hugos over to a different topic entirely: science fiction and the military.

Military Writer’s Guild

First off, some personal news: I’m happy to say that I’ve been accepted into the Military Writer’s Guild! The organization gathers writers who write about military affairs, something I’ve done over the years with fiction and nonfiction alike, and something that I’m planning to continue with.

Here’s a bit about the organization and its goals:

The Military Writers Guild exists to gather writers committed to the development of the profession of arms through the exchange of ideas in the written medium.

Through its members, The Guild will encourage an open dialogue from diverse perspectives, thereby supporting the study of military affairs, spread knowledge of the military profession, and increase the assistance available to those writing in the national security space.

Writing Future War

I’m very happy to say that I recently published a big post on Medium’s tech site OneZero: The U.S. Military Is Turning to Science Fiction to Shape the Future of War. It’s a topic that I’ve wanted to write about for literally years now, and I was happy that editor Brian Merchant picked it up for the site.

I’ve long been fascinated by how warfare is depicted in science fiction. I got my Master’s degree in Military History, and when I started writing about science fiction, it was a topic that I focused on. Then, way back in 2014 (six years ago now — 😱) my friend Jaym Gates and I co-edited a science fiction anthology, War Stories: New Military Science Fiction, with the intent of updating the look and feel of military SF. We put together a killer list of stories, and I ended up publishing my own military SF story for Galaxy’s Edge Magazine, “Fragmented.”

Little did I know at the time, but there was a growing movement within the military to look at the future of warfare through storytelling. August Cole of the Atlantic Council, and P.W. Singer of The Brookings Institute published a novel called Ghost Fleet, about a third World War scenario in which the US, Russia, and China all go to war. Cole also stood up a project within the AC to encourage more of this fiction, and in the years since, he’s been a driving force, heading up workshops, writing his own stories, and generally pushing for the military to use fiction — which he calls FicInt, for “Fictional Intelligence” — to think about what’s coming down the pipeline.

Here’s an excerpt:

These stories aim to address some of the biggest questions about the fast-changing nature of modern warfare: How will artificial intelligence change how decisions are made on the battlefield? What does the introduction of UAVs and autonomous robotic systems mean for the rules of engagement? These problems are difficult to test in the real world. So, in the past decade, various groups within or adjacent to the military have increasingly turned to science fiction, using anthologies, graphic novels, and books to visualize the battlefields we might someday find ourselves fighting in.

Give the story a read here.

What’s interesting to me personally about this small movement is that it feels like it’s something that gets back to the heard of the earliest spirit of science fiction: it’s a genre designed to deliberately encourage creativity. The earliest science fiction magazines saw stories about science and technology as a way for people to grapple with those topics and to then translate their imagination into concrete goals. China’s early history with science fiction is rife with this attitude. FicInt seems like a bit of a mutation on it: a specific, purpose-built exercise to help people in the military industrial complex to try and figure out what’s coming next, rather than fighting the last war and having to catch up — as we frequently do.

This isn’t to say that everyone involved sees this as championing MOAR WAR. The opposite. Karl Schroeder, who I interviewed for the piece, noted that he comes from a Mennonite and pacifistic background, while most people I spoke with saw this as a way to try and be smarter about how and when we use force. At some point, if folks are interested, I can put together a reading list of stories to read if they want to check these types of stories out. (Let me know in the comments?)

The Real Robotic Revolution

In 1920, Czech playwright Karel Čapek published an unusual work: a play called Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti, or Rossum's Universal Robots. Brave New Words: The Oxford Dictionary of Science Fiction cites the play as the first use of the word “robot,” and ever since, robots have been a fixture of science fiction drama, used by countless authors throughout science fiction’s long history, who have imagined all of the ways that they could break, help, murder, or otherwise exist alongside humanity.

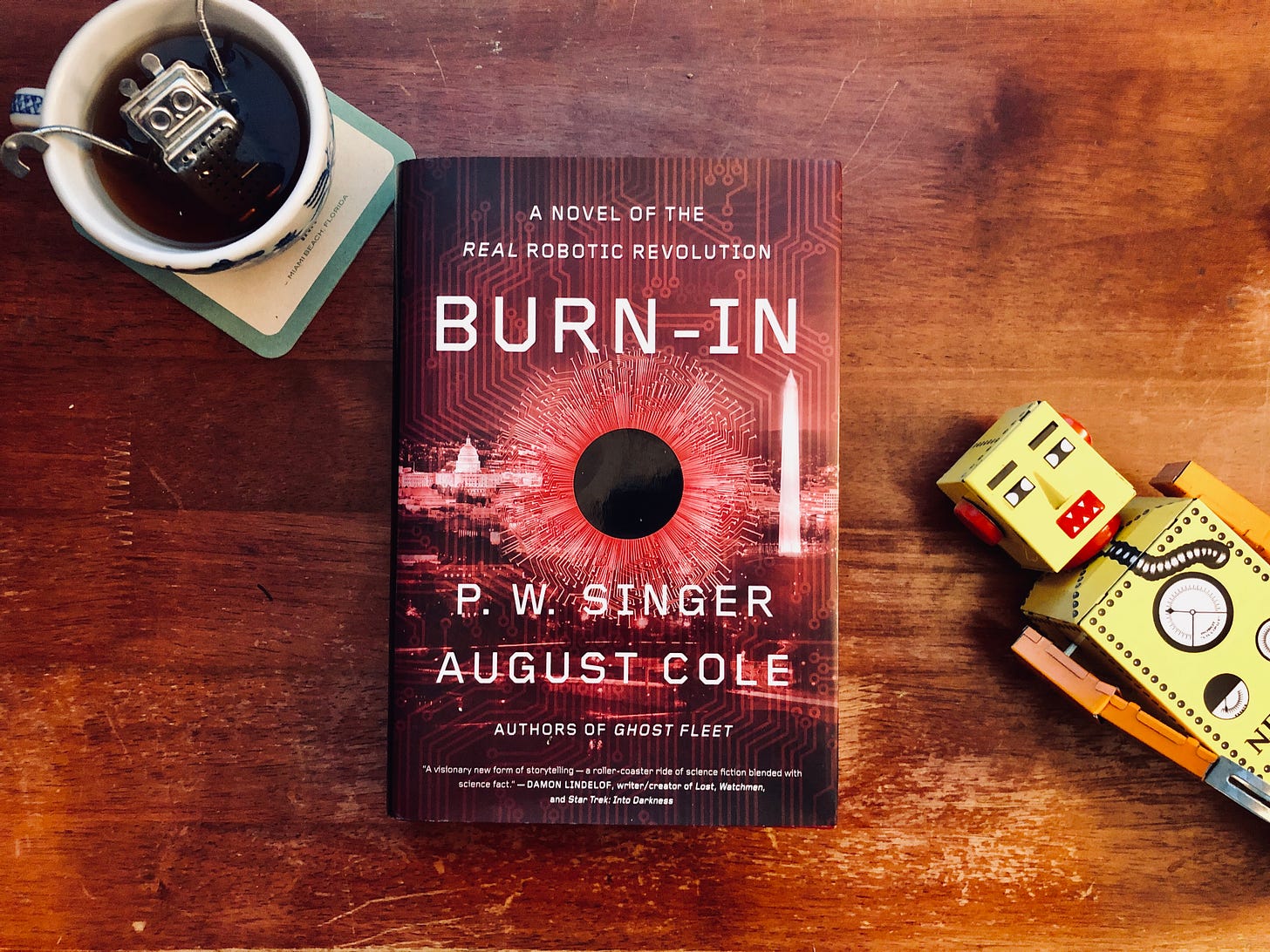

One of the latest books to look at the world of robotics is Burn-In: A Novel of the Real Robotic Revolution by P.W. Singer and August Cole. The two collaborated on 2015’s Ghost Fleet: A Novel of the Next World War, a near-future thriller that blended the then-present-day advances in military hardware with geopolitical friction between the United States, Russia, and China. The result is a book that’s eerily been coming true, piece by piece. Now, the pair replicate their approach to look at what the near future might hold for robotics.

Set in the 2030s, the pair depict a future that feels like it could come true tomorrow. FBI Special Agent Lara Keegan goes about her work trying to capture a suspect amidst a wide-scale Veteran protest and series of domestic terror attacks, aided by facial recognition that’s beamed into her glasses, self-driving cars, origami drones, and more. She’s soon tasked with a new partner: a police robot called TAMS (Tactical Autonomous Mobility System). Her job is to give it a shakedown — a burn-in field test to see if it’ll be useful to officers in the field, and to help it better understand human interactions. TAMS proves to be a useful partner as she and her fellow agents work to track down an extremist bent on a major attack in Washington DC.

TAMS is certainly the highlight of the book — it’s simultaneously inhuman, but is fleshed out nicely: you can’t help but imagine that it’s sentient. It’s something I (and soldiers who have worked closely with robots on the battlefield) can relate to a bit: I’m very attached to my home’s Roomba, Rosie (and “her” newer sibling, Robbie.) The same is true with TAMS.

This is the key to the success of Cole and Singer’s brand of science fiction (the aforementioned FicInt, of which this is an example): it has a foot firmly planted in reality, while stepping forward in time a bit by extrapolating forward from 2020. This worked for Ghost Fleet, in which we see a range of then-theoretical or novel military technologies like drone swarms, automated ships / vehicles, hijacked tech because of poor supply-chain security, and so forth. While Cole and Singer still have their eyes on the future of the military, the building blocks that they’re playing with here show how porous the barrier between military and civilian technologies. Their characters stock up on food with apps and algorithms, appear in bystander videos that go viral, and contend with hacks and cyberattacks against insecure public infrastructure.

If some of those items sound familiar, it’s because they’re all things that have taken place. Novels usually carry a disclaimer in the front that says that the story and characters are fictional. In this novel, it reads: “The following is a work of fiction. However, all the place, trends, technologies, and incidents in it are drawn from the real world.” The end of the book has a thick section of footnotes of links to technology news from the last couple of years, everything from data security to robotics.

But what makes Burn-In a bit more of an effective read is that Cole and Singer don’t just focus on the technological gains that we can expect in the coming decade: they look at the effects of automation. What happens when you have a huge number of white men thrown out of work because their jobs have been automated out of existence? Keegan’s ex-husband is a good example here: he’s getting by as a gig worker helping elderly clients navigate their lives virtually, and is getting more radicalized by politicians and internet commentary that’s designed to steer people towards a more right-wing worldview (in this case, it’s also presented as very anti-technology).

This is an idea that’s central to robotic stories, because it’s fundamentally about how they change how we live. Cole and Singer aren’t arguing that robotics are bad in Burn-In: we plainly see how useful these things can be. But they’re warning that robotic, computer, and autonomous systems as we’re currently designing them are fragile — as are the cultural, political, and social systems that we live with today.

Apps that summon autonomous delivery robots aren’t the problem: it’s that they’re implemented without thought for the larger context in which they fit into the world. Uber, for example, has decimated the traditional Taxi market. On-demand delivery services and platforms are having a terrible effect on local restaurants and eateries. In doing so, Cole and Singer demonstrate the value of this type of fiction: it helps identify potential breaking points by framing them in a dramatic way, and Burn-In serves a bit as a warning sign for how things could go. It’s a scary future that they present, and in all likelihood, much of it is going to become very, very real.

Currently Reading

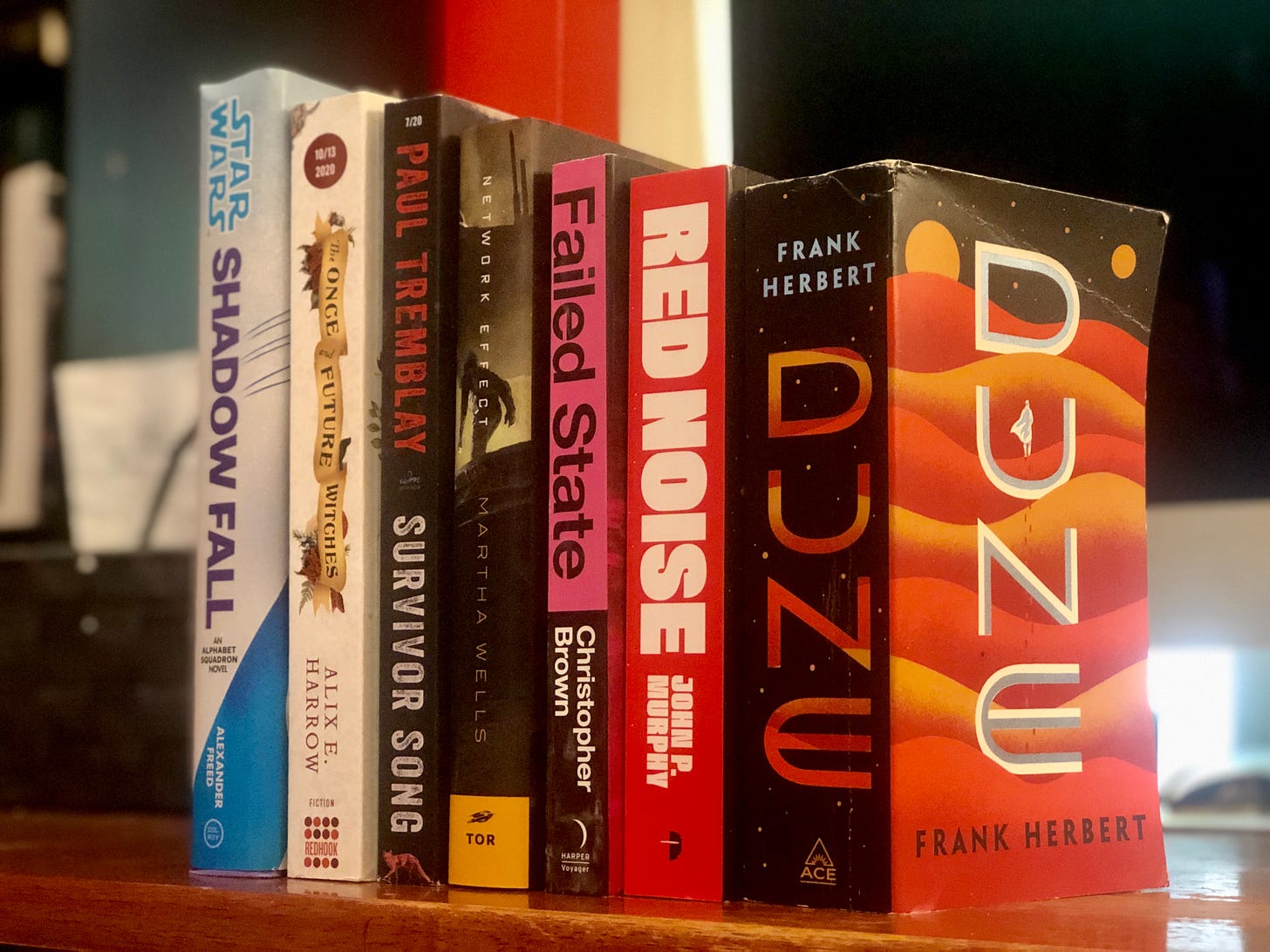

I’ve been in a book rut the last week or so. I don’t know exactly what it is, but I’ve been jumping from book to book, trying to find the right thing that’ll catch me. Right now, I’m working my way through Frank Herbert’s Dune, and I’ve been cycling through Liquid Crystal Nightingale by Eeleen Lee and Survivor Song by Paul Tremblay. I’m also picking up Christopher Brown’s upcoming novel Failed State, the sequel to his excellent novel Rule of Capture.

Others on my to-read list are Martha Wells’ Network Effect, John P. Murphy’s Red Noise, Alix E. Harrow’s The Once and Future Witches, and Alexander Freed’s Star Wars: Shadow Fall.

Further Reading

- Arthur C. Clarke & Wonder. Lithub posted John Clute’s enlightening introduction to The Folio Society’s edition of Rendezvous With Rama. (My interview with Matt Griffin, who illustrated the book is here.)

- Revisiting Ballad of Black Tom. Charles Pulliam-Moore over at io9 revisits Victor LaValle’s The Ballad of Black Tom, a take on Lovecraft’s short story The Horror at Red Hook, inverting its racist tropes.

- COVID Bookselling. The New York Times talks bookselling in the era of COVID, and noted that major retailers like Costco and Walmart found that book sales picked up when they were placed in the right areas of the store — next to toilet paper and groceries. It’s an interesting thing to see, given that genre books have historically been sold in grocery stores — before distributors collapsed in the 1980s.

- Dystopian Fiction. In case you didn’t get enough of August Cole and P.W. Singer in this letter: they talk about the value of dystopian fiction over on Slate’s Future Tense section: “Yet the value of the genre is as much in education as entertainment. It can elucidate dangers, serving the role of warning and even preparation.”

- Emergence Trilogy: A friend of mine, Aaron Sikes, recently released his Emergency trilogy as a boxed set. You can find details here.

- Exploring the Solar System. The New York Times has a super-cool infographic that shows all of the spacecraft and satellites that have explored the solar system.

- Inverting Lovecraft. I’m a big fan of Eric Molinsky’s Imaginary Worlds podcast, and in a recent episode, he talks about The Ballad of Black Tom and how there is a recent movement of authors of color who are inverting Lovecraft’s racist tropes.

- J.K. Rowling. Nathan J. Robinson has an excellent (long) piece looking at the disconnect between J.K. Rowling’s attitudes towards trans people and the ability to dream up an entire fantasy world.

- Lost Rocket. Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson has a phenomenal feature in the Washington Post Magazine about a man’s attempt in the 1920s to build a rocket that would go to Venus, and more recent attempts to try and track it down.

- Return to the Far Side. Gary Larson, the cartoonist known for the zany cartoon Far Side made a return recently with a new website and some brand new cartoons. I’ve loved his cartoons since I was a kid, and this is a neat profile of him from The New Yorker.

- UX of LEGO. This is a super-fun piece about the user interfaces of various LEGO consoles.

- Tade Thompson Profile. Dalya Alberge at The Guardian has a great profile of author Tade Thompson, who’s best-known for his Rosewater novels. I hadn’t realized that he was a practicing psychiatrist.

- Tuckerized. Over on The New York Times, journalist John Schwartz talks about how he ended up in a fictional newspaper article in Mary Robinette Kowal’s The Relentless Moon.

That’s all for this week: thank you for reading! Let me know what you have on your to-read list, and what you’re looking forward to.

Coming up: I’ve got some interesting things in the pipeline: a couple of posts for paid subscribers, and hopefully, another review round up of some recent books.

Andrew