Fan fiction is the lifeblood of fandom

Fan fiction's strength isn't based on its literary merits, but on the fans that it brings together

When I was a teenager, Star Wars was everything. I watched the films constantly, I read every book I got my hands on, spent an ungodly number of hours on message boards, and wrote for a bunch of fan sites over the years. And when I ran out of stories to re-read for the umpteenth time, I started writing my own stories.

They weren’t good — just rehashes of story beats and collections of action scenes that I enjoyed, with the added bonus of being able to incorporate elements from the Prequel trilogy into the post-Return of the Jedi era. I don’t remember exactly what I was writing about, but it had something to do with smugglers transporting old battle droids in an attempt to overthrow the New Republic.

I wasn’t alone in that desire to take my favorite property and tell my own stories in it: I read tons of stories by other, fellow fans on message forums and on platforms like FanFiction.net, where other fan authors penned their own takes on just about every other film that you could think of.

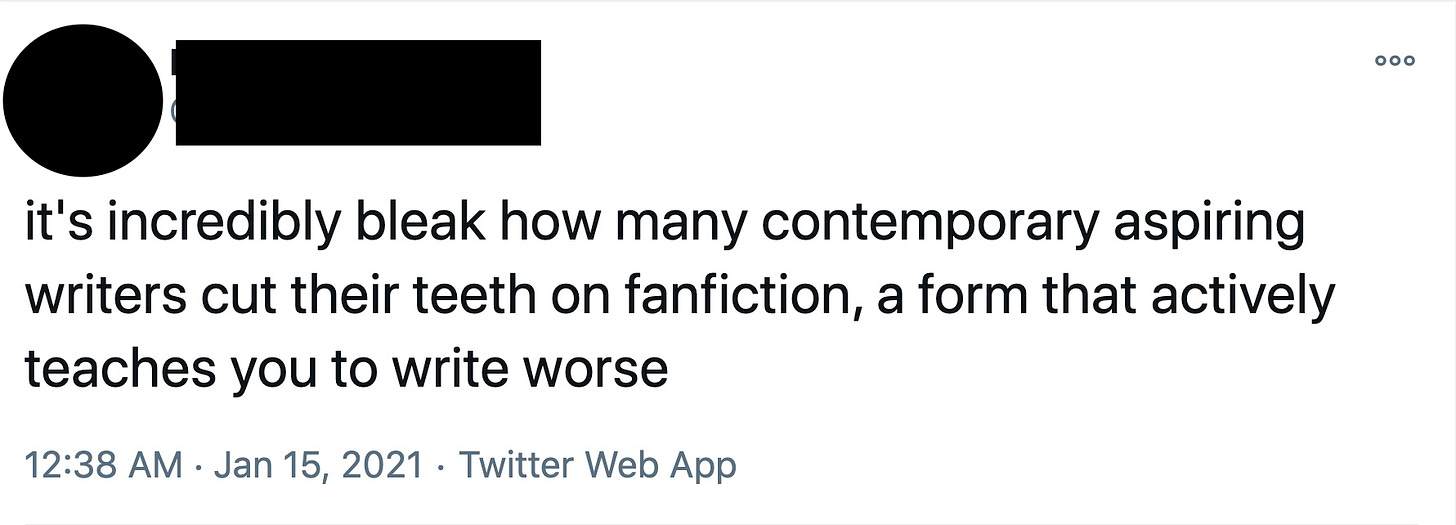

There’s a bit of discourse taking place on SF/F Twitter, thanks to one author’s take on the form:

The author followed up with some additional complaints: that it’s formulaic and full of bad writing, that the scene as it exists has driven people to ignore queer literature, and that folks indulging in it are simply unimaginatively recycling IP held by corporations.

It’s a bad, petulant take that’s perfectly constructed for social media, and while I don’t know the basis for this particular author’s complaints, but it’s certainly not the first time that those criticisms have been aired. Fan fiction has always been a bit of a punching bag for some writers, and it’s part of a larger argument: that to be valid, storytelling has to be completely original, and that stories that serve to expand a larger story IP are somehow a lesser form — a misguided assumption and mindset. And it’s been with us for a long, long time.

By 1837, Edgar Allan Poe had established himself as a notable American poet and writer in America, one who had begun to explore themes that would eventually form the roots of both speculative and detective fiction. With stories and poems like ‘The Fall of the House of Usher,’ ‘The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall’, and ‘The Raven,’ he established himself as a major fixture within the American canon, one with plenty of readers around the world.

In 1837, he published his first — and only — novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket. The story follows its titular character, who stows away on a whaling ship, only to get immersed in a fantastical series of adventures, facing storms, mutinies, hostile islanders, all before discovering some fantastical caves before ending abruptly.

The novel captivated readers at the time, including one particular French author, Jules Verne. Verne was a huge fan of Poe’s work, and noting that The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket was as of yet incomplete, decided to finish it. The result, which he published in 1897, was the two-volume novel An Antarctic Mystery, in which Verne picked up the story with a new narrator, who eventually encounters Pym, and continues the adventures into the arctic. A couple of years later, another author, Charles Romeyn Dake would pen his own sequel to The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, A Strange Discovery. This novel was set nearly 50 years later, picking up some of the same characters as they traveled through the arctic.

In many ways, An Antarctic Mystery and A Strange Discovery are early forms of fan fiction: authors taking up an existing work and continuing the story with their own, transformative works. Poe wasn’t the only one to find devotees repurposing his characters: many authors took on the works of Jane Austen or Arthur Conan Doyle, H.G. Wells, and more. At its core, it’s a story written by a fan of a work that utilizes pre-existing characters and features from said work.

But there’s an additional bit of social context that’s been layered on. Brave New Words: The Oxford Dictionary of Science Fiction tacks on “amateur” to its definition, and that the first use of the term came in 1939 in fanzine Le Zombie, in which the author used it as a way to differentiate between professionally and fan-written works. That’s a distinction that’s lingered ever since: the idea that the works written by fans are inherently lesser than their professionally produced counterparts.

Fan fiction as we know it today really gets its roots out of Star Trek fandom. While organized fandom had existed since the 1920s and 1930s, Gene Roddenberry’s television show was a huge, mainstream introduction for the American public, and it brought a tidal wave to what had previously been an activity limited to just print material. The result was a bit of a culture clash. Traditional science fiction fans found a lot to like with Star Trek — indeed, a number of writers on the show came out of the literary world — but many looked down on Star Trek devotees.

A year or so ago, I spoke with an older member of fandom, who told me that there was the overwhelming feeling that while it was great to get more people interested in science fiction, the Star Trek folks just weren’t interested in expanding their horizons. They saw them somewhat as lesser fans, ones not interested in the larger history and community of traditional fandom.

Not entirely welcome in Fandom, those fans simply took the tools that their predecessors had used and made their own fan networks, launching their own Star Trek fanzines and conventions.

With those outlets, they wrote their own adventures of the USS Enterprise. Writing in Star Trek Lives! Jacqueline Lichtenberg, Sondra Marshak, and Joan Winston note that fans devoted hundreds of pages and words to the franchise “for the sheer love of Star Trek. People have become so entranced with that world that they simply cannot bear to let it die and will recreate it themselves if they have to.”

NBC had canceled Star Trek a decade before that book was written, but the series had gotten a resurgence because of syndication, bringing new fans in thanks to a constant tempo of reruns. With the prospect of the end of the series, taking on the task of continuing the adventures of Captain Kirk, Mr. Spock, and Dr. McCoy fell to those devoted fans.

“The stories ranged from outright sexual fantasies — not a few of them so flaming that they circulate only very privately or even never get out of their author’s most secret drawers — to straight adventure, to tender love stories, to hilarious parodies, to provocative, voluminous long-running series fiction like Kraith.”

While there’s been a line drawn in the sand between “professional” fiction and “fan” fiction, there’s a distinction that’s often overlooked by critics: the underlying reason for why fans would choose to spend their time in worlds that they aren’t creating — and it’s often part of a larger misunderstanding (or a disunderstanding?) to recognize why fans are particularly devoted to various media franchises, from Star Trek to Star Wars to A Song of Ice and Fire / Game of Thrones. The mass of fan-written stories out there span the width of poorly-written drivel to great, but that’s not really why they were written in the first place.

In essence, fan fiction is a vital part of holding together a cohesive fandom — it allows a fan movement to go beyond passive consumption and engage in creating, interpreting, and remaking said franchise on their own terms. Fan fiction isn’t written to please outside audiences: it’s written as a means of communicating with other fans, reinterpreting and building on the thing that they collectively love. It’s a way to explore characters and stories, and contribute to vibrant community, building those worlds out without constraints.

Star Trek fandom is infamous for introducing the concept of “slash” fiction, where a fan writer pairs up two unpaired characters (usually of the same sex). Those stories will likely never see print or be part of canon, but by endlessly remixing and experimenting with characters, worlds, and stories, they can find new meanings for those stories they love, and work out those ideas collaboratively with other fans.

“Fan fiction is part of a community,” His Majesty's Dragon author Naomi Novik told io9 back in 2010, “it’s not just written for one single person speaking to an audience: it’s written in a network, frequently stories communicate with one another, they communicate with what’s canon at that particular moment in time.”

The arguments against fan fiction (that it’s formulaic, poorly written, that there are other things to engage with, or that they’re wasting time writing in a pre-existing IP) largely fall short of the actual intentions of fans. All of those arguments might be true, but they miss point: the authors aren’t (generally) trying to produce a product: they’re producing discourse and dialogue and connections.

These of fan activities (of which I’d argue that cosplay is a key part) are unconstrained by physical spaces, and are critical for bringing in marginalized fans, who might not otherwise be permitted into traditional fandoms. Star Trek’s cosplay and fan fiction scene were predominantly led by women and members of the various LGBTQIA+ communities.

The internet has been a boon to these fan networks: forums and newsgroups allow them to organize, and platforms like FanFiction.net and Archive of Our Own (which has since been honored with a Hugo Award for its contributions to the larger fan community!) have provided outlets for fans to post and share their work with other fans. And plenty of mainstream, successful authors have pointed to their fan fiction as a valuable learning experience for learning how to write.

Authors like Novik have touted their experiences writing as a valuable learning exercise. The City We Became author N.K. Jemisin told The Atlantic back in 2019 that she began writing Dragon Ball Z fan fiction as a way to find a community and build up her writing skills. “You have to find a way to make it not just the world that people are tuning in to read, so they are interested in your story.”

But for all the advantages that the form has when it comes to community, bringing in marginalized communities, or with helping authors boost their writing skills, sometimes, fan fiction happens for one very simple reason: that getting to write a story and play in some existing world with some favorite characters is just plain fun.

It shouldn’t need any more rationalization than that.