Wordplay: What is the role of optimism in science fiction?

Hello!

Welcome to issue #4 of Wordplay! (You can read the past issues here)

I’ve alluded to a big project being launched in the last two letters, and it’s finally been revealed: The Verge is launching an online anthology called Better Worlds in January! It will include 10 original science fiction stories that feature optimistic visions of the future. It’s something we’ve been working on for months, and there’s an incredible group of authors in the table of contents — Justina Ireland, Carla Speed McNeil, John Scalzi, Leigh Alexander, Rivers Solomon, Cadwell Turnbull, Elizabeth Bonesteel, Kelly Robson, Karin Lowachee, and Peter Tieryas. I’ve read all of the stories, and they’re really good. You should definitely keep an eye out for it when the first one hits the web in January.

Optimism in Science Fiction

Better Worlds is a good excuse to talk about the role of optimism in science fiction — something that’s been highlighted in many reactions to the launch of the project, given how absolutely crummy the real world is right now. It's a perennial argument in SF circles: people complaining that everything is just too dreary — authors these days don't do it like they did in the good old days! I don't think that's a particularly convincing argument, but there certainly is a place for optimisim in SF, and there are plenty of recent books out there that earned a considerable praise and attention for their optimistic futures. Andy Weir’s The Martian springs to mind, as does Kim Stanley Robinson’s New York 2140, Malka Older’s Centenal Cycle, and Ed Finn and Kathryn Cramer’s anthology Hieroglyph: Stories and Visions for a Better Future.

The tone of science fiction does reflect the times, and there’s plenty to be pessimistic about right now. Climate change is having a noticeable impact on how we live, the bad parts of technology and globalization are starting to catch up to us, and all of those visions of people living on moon bases and in satellites certainly isn’t going to be as romantic as the pulps made them out to be. And there's a whole host of great — but dark — SF out there tackling and interpreting the present, like Paolo Bacigalupi's The Windup Girl and The Water Knife.

It’s hard to pin down exactly what an “optimistic” science fiction story is. Is it tech-positive, where people look at and imagine technology fixing everything? Or is it something where we just bury our heads in the sand and try to ignore our culpability in some of the bad things in the world? Is it literally just a story that doesn’t imagine the world as a dark and dreary place and looks at the better side of humanity?

I’ve come to see this in a couple of different ways, because I think all apply. There’s certainly a regressive strain here that encompasses non-cynical books like The Martian. I see Weir as a reductive author. He has a worldview that really seeks to ignore some of the more troubling problems in the world, telling me a while back that he avoids politics because he doesn’t “like reading stories with a political message,” because he finds them preachy and that they mess with his ability to enjoy the story. That’s all well and good person to person, but I think it’s a pretty narrow-minded view of what fiction can offer to its readers, and it blunts the impact of what fiction can accomplish.

Optimistic SF doesn't mean that a work is free from a critical examination of the world — and there's no such thing as apolitical fiction. Take Kim Stanley Robinson’s New York 2140. It’s a book about climate change with some very heavy messaging, but it's largely an optimistic read about people adapting to this enormous upheaval that is climate change. Mind, he skips over some of the brutal stuff, like wars, famine, and genocide. But it’s a generally positive outlook on what people can accomplish, and most of his works are about similar things — people coming together to do great things. His other reads, like 2312 is similar.

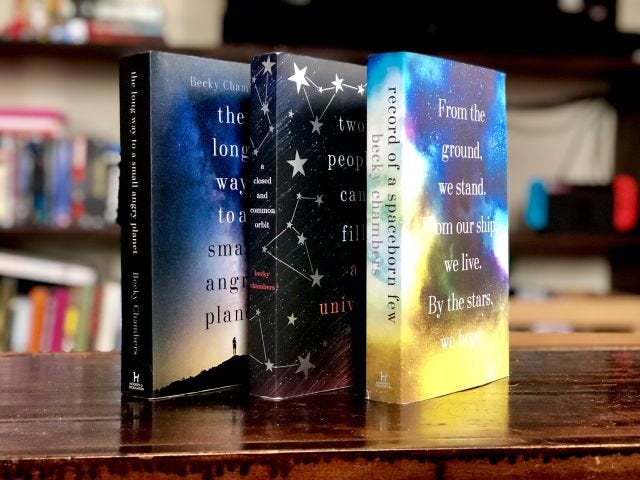

With that in mind, there’s a trilogy that I particularly want to single out, because it’s a good example of fiction with a positive outlook on the world that doesn't really skip over the things that challenge humanity: Becky Chambers’ Wayfarers trilogy: The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet, A Closed and Common Orbit, and Record of a Spaceborn Few. The latest book came out earlier this fall (I need to do up a formal-ish review of it for my blog), and it’s fantastic.

Chamber’s series (they're really standalone installments that share a world) is set in an inhabited galaxy in the distant future. Humans are just one species amongst many, and live alongside one another in a number of habitable planets, stations, and starships. The first book, The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet follows Rosemary Harper as she joins the crew of a starship, The Wayfarer, which is tasked with developing interstellar travel routes. The book is pretty nebulous — it just follows the characters as they set up a new, potentially dangerous route, and digs into their various lives. The next book, A Closed and Common Orbit, is a bit more story-oriented. It builds off of the end of The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet, following Lovelace, an AI who downloads itself into an android body and meets a woman named Pepper. A parallel storyline traces Pepper’s origins as a genetically modified slave who grows up alongside an AI in a wrecked spaceship. The third and latest book, Record of a Spaceborn Few, follows the inhabitants of the Exodus Fleet, the original fleet of ships that left a wrecked Earth eons ago, and their efforts to maintain their unique culture and society, even as people leave for better opportunities elsewhere, and as their spaceships begin to disintegrate with age.

Chambers’ world is bright and vivid, and each of her stories really focus on one thing: identity in a chaotic world. There’s elements of these books that are gritty and decidedly not optimistic — murder, child slavery, wars, famine, climate change, etc. But it's her focus on how people forge their own identities or build loving communities around them that makes her stories stand out. These aren't adventures of people fighting against the inequalities of the world, but building better futures for themselves and those around them. Each book focuses on a whole range of elements to this: gender, religious, and sexual identity, and for the most part, her characters are free to both exhibit themselves and their identities as they see themselves. They're challenged not by people trying to tear them down, but of the larger, structural problems that they encounter, things like pushing against a society that is resistant to change in Record of a Spaceborn Few, or helping a character discover who they are and to be comfortable in their own skin in A Closed and Common Orbit.

There’s a lot to learn from these books, because what Chambers isn’t doing is ignoring the structural problems that societies face, but folds them into her world, where characters simply have a different mindset and approach to addressing the issues in their world. They’re not afraid of their neighbors, strangers, or literal aliens: they recognize the potential that can occur when people of all types come together into a community. That, I think, is something we all could use more of, in fictional and in real worlds.

Further Reading

There were two long reads that came out since my last newsletter that I’d like to point to. The first is by Brian Merchant in Medium: “Nike and Boeing Are Paying Sci-Fi Writers to Predict Their Futures”. Merchant takes a look into the world of corporate storytelling, where companies like the aforementioned hire specialists — science fiction writers — who help come up with plausible futures. This isn’t just an exercise in vanity on the parts of Nike and Boeing: given the scale of the companies, it makes sense to have some sort of idea of the world that they’ll be operating in, not only from a data and analytical standpoint, but an emotional one as well.

The other one is a fantastic profile of writer N.K. Jemisin in Vulture, written by Lila Shapiro. I’m a huge fan of Jemisin’s — I really liked her debut novel The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms, but I was even more impressed with her latest epic, her Broken Earth trilogy, which I’ve written about at length for The Verge. Jemisin has earned some well-deserved acclaim for her works because of her approach to science fiction and fantasy literature. The Broken Earth trilogy blends elements of science fiction and fantasy, and Vulture notes that her works pull in some considerable — and much-needed — social commentary. “If I write about dragons,” She tells Shapiro, “I’m writing about dragons as a black woman, and it’s fucking political.”

This is something that’s badly needed, in my view — while there are certainly contingents of fans who maintain that they want their fiction to be apolitical, that’s something that really doesn’t exist. There’s a disparity in how people view SF/F — the white, conservative futures that came out of fiction in the 1950s is a political future, and Jemisin is pushing against a history of momentum, both exposing that “traditional” attitudes toward fiction has its own agenda, but also that it’s … not the only viewpoint or approach to fiction that’s out there. Which is apparently upsetting to people, particularly stalwarts in the genre like Robert Silverberg and Gregory Benford.

A couple of other things that I wrote for The Verge that I’ll steer you towards: I spoke with Nightflyers showrunner Jeff Buhler about adapting George R.R. Martin’s original novella. I recently read the story, and it’s fine — there’s some awkward racial things in it, which hopefully the TV show will fix. I also posted up December’s book list, of which there are some interesting ones coming out this month.

Reading List

Since my last letter, I’ve since finished R.E Stearns’ Mutiny at Vesta. I might have a longer review of that at some point — she has some interesting takes on AI, but the long and short is that it’s not as good as Barbary Station, which I really adored. I like the world, I liked the story and action, and most of all, the characters, but this one just felt like it dragged just a little too much, and that it probably could have been slimmed down a little to tighten up the focus a bit. Still, I’m really looking forward to whatever she has coming up next.

I’m currently reading Jemisin’s new collection, How Long ‘Til Black Future Month, which is fantastic — if you want a good taste, go head over to Tor.com and read her 2016 short story “The City Born Great”. It’s a good one. I’m also working on Lavie Tidhar’s Unholy Land, Larissa Lao’s The Tiger Flu and Robert Jackson Bennett’s Foundryside, and I'm hoping to get to John Scalzi's The Consuming Fire at some point before the end of the year. And Richard K. Morgan's Thin Air.

That’s it for now — I need to pack for a quick trip to Toronto this week (more on that later). As always, thank you very much for reading — I appreciate the responses and the word of mouth that has bubbled up. If you find this useful or enlightening, forward it on or tell a friend about it.

Andrew