The substance of space and the human imagination

Science fiction artist John Harris on inspiration, the beauty of space, and why AI can't capture creative imagination

One of the joys of writing about science fiction (and this particularly this newsletter!) is the opportunity to talk with folks about how they go about their craft, whether it's a writer talking about their latest book, a historian about their research, or an artist about putting paint to canvas.

Earlier this summer, I had the opportunity to interview an artist that I've long admired: John Harris. You've likely seen his work before: he's known for his abstract, impressionistic science fiction art, blending vivid colors with jagged spaceships and megastructures that grace the covers of books by authors like Ben Bova, Mike Brooks, Orson Scott Card, Ann Leckie, Larry Niven, John Scalzi, and many, many others.

His art is the perfect invitation to any science fiction novel – I've often picked up books based on his art alone. In 2014, he published an art book, Beyond the Horizon, a beautiful selection of his artwork, and in 2022, he released a follow up, Into the Blue, which takes another probing look at the worlds that he created. Both are well worth picking up – I've spent hours flipping through the pages.

Over the summer, I had the opportunity to chat with Harris and jumped at the chance to talk about his process, thoughts on the cosmos, creativity, and what he thinks about generative artificial intelligence.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

To start off, tell me a bit about how you got started as an artist – or let me go back even further: which came first, your interest in science fiction or an interest in art?

Now, that is a really difficult question for me to answer because there was no separation (and never has been any separation) from the feeling that I got by reading people like Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov and that lot.

The visual connection with me was immediate, and I couldn't help read stuff without immediately seeing imagery. It was absolutely inseparable and has remained so throughout my whole life. As far as back as I can remember I've always had this sense of wonder about space and the stars and stuff like that, and that was it seamlessly connected with the science fiction that I read.

I suppose it's almost like when people ask me, how did you start doing art? And I say, "I don't remember!" [It was] long before I went to art college – I went to art college in 1966, and yeah, it was always there. I would imagine it's a feeling related to looking at the sky was the beginning. I just can't separate it.

Were there any books that have stuck with you from that time, or which still stick with you today?

Yes, absolutely. To begin with, I think they're almost all [from] Arthur C. Clarke – books like Childhood's End, which was a particularly big one for me. I can't remember going back that far or what I read, but certainly I would say that if I had to pin anyone down, it would be Clarke.

I ended up going to see him many years later as an adult in Sri Lanka. He was already quite an old man. When I showed him some of my work, he got quite excited by that.

I know here in the United States, science fiction always had this taboo around it – it wasn't considered a serious body literature. So when you went to school, what was the general attitude towards it?

Yes, it was never taken seriously, and in a way, I was looked upon as a bit of an oddity. Even though I learned to do traditional painting, everybody knew that [science fiction] was really what I was interested in – this peculiar relationship between the planet and the stars.

I had these photographs of various galaxies in my digs, which was a real little hovel. I remember one of the tutors visited me, and [when] he saw the stuff on the walls, he says, "this will make you mad, you know." I said, "well, I'll take the chance." [laughs]

That's never changed, really. One thing that is interesting about that is that I've always been very interested in making images, whatever they were, and that was probably how I got into art college in the first place. I remember when I was very young, about 12 or 13, the art teacher at my school was sort of wandering around and he looked at what I was doing – it was a picture of it was a picture of a poster of a Brigitte Bardot movie with this voluptuous picture of Bardot sort of spread across this poster, and I was just copying it. He looked at what I was doing and said, "you're going to be a painter."

I didn't have the faintest inkling of what that really meant, and I just sort of innocently went along. He was particularly struck by the way I used color, and I think that was how I got a sort of a footing in the whole thing, learning to you express myself with color.

I'm guessing you reading science fiction in the 1950s-60s: what was your impression of the cover art of the time?

I'm gonna be really unpopular now, because I've got to say it was one of the reasons why I got into it: I couldn't bear the artwork. It seemed so naff, you know? It seemed in comparison to the imagining of this amazing domains of stars and gases and that these were rather dreadful pictures.

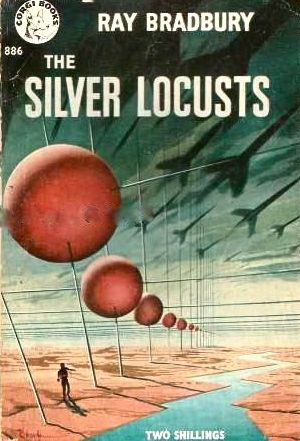

I remember getting a wonderful Ray Bradbury book called The Silver Locusts (published as The Martian Chronicles in the US) and thinking, "I can't bear to be seen reading this stuff. I've got to put a cover on it, to hide it." It was really embarrassing to be caught with this sort of pulp picture.

I'm sorry, I'm being super critical here, but that was the reality that I had. Particularly when I was at art college, I'd be reading some of these pieces and that's the level of criticism you'd be threatened with.

I have both of your books, The Art of John Harris: Beyond the Horizon and The Art of John Harris Volume II: Into the Blue, and the thing that strikes me the most while reading them was how you use color. Space is dark, but you've gone the other way with these vivid colors. How do you go about conceiving an image?

So yeah, the business is about going about finding the image and the color and all of that is a very subtle business. For me, it's largely about holding a feeling of – quite often – the title alone. As I mentioned in Into the Blue, the power of words has always been for me what generates its own imagery. Quite often, without even reading the book, I only need a phrase or some kind of a guideline as to what the book is about. Depending on the words that are chosen to describe it, I immediately have an image.

The power of words has always been for me what generates its own imagery

My agent frequently used to ring me up when I did a lot of cover art saying "I've got a book for you." I'd say "just give me a basic idea. What's it about?" She would start telling me the plot of the book and I'd go "All right, I've got it now."

It may not have much to do with the actual content of the book, but it will have something of the feeling of it. You know, I can't tell you how that happens. It's a bit of it's a bit of a magic thing for me.

It's a vibe, as the kids say these days.

It's a vibe. It absolutely is a vibe. It's a vibration. It really is that. I don't fully understand it, but I've learned not to question it, because as soon as you start to do that, you end up with something that the brain decided that it had to do it and not the heart.

I've learned not to question it, because as soon as you start to do that, you end up with something that the brain decided that it had to do it and not the heart.

Overthinking it.

Overthinking it is probably the biggest sin this one can do, I think. It really is a very delicate and subtle dance between the first impulse of feeling and it's almost impossible to talk about.

One thing I'm fascinated by about is the interplay between science fiction writers who are imagining worlds and the astronomers who are showing us the universe.

You've seen the space race play out with all of these incredible technological advances like satellites and orbital telescopes. How has that played a role in your work?

It has been enormously important. But again in a quite a subtle way, not in the most obvious way.

When I was very young, I must have been no more than 12, 13, or 14, I saw a program from the National Film Board of Canada about the current state of astronomy and our view of the galaxy and all of this stuff. I remember watching it and thinking, "that's it. That the shape." – this might sound a bit odd – "that's the shape of my dreaming,"

Interestingly enough, this film also influenced director Stanley Kubrick when he was putting together what eventually became 2001: A Space Odyssey.

I fell into it this sense of wonder about the universe, hook, line and sinker. That is probably the germination of what eventually came into fruition, as it were: this extraordinary black and white film of the newly discovered optical images of the galaxies.

Have you been paying attention to the images that the James Webb Telescope has been sending back?

Yes, I have. It's a funny thing. I mean, the deep field ones are just astounding. I expect a lot of people will find this a bit disturbing, but to me, there is a very deep connection here between what I would call spirituality and science.

I cannot look at the deep field images by the James Webb Telescope without having this recurring sense that actually this is the realm of the spirit

I cannot look at the deep field images by the James Webb Telescope without having this recurring sense that actually this is the realm of the spirit, and I include the [bang] hard desk – on which I'm hitting my hand – with the same substance as what is out there and that what's out there is the same substance as my spirit.

That reminds me a little bit of the Overview Effect, when the first astronauts went up into space, they were talking about how they were profoundly changed by just looking back at the Earth. William Shatner recently went up on one of Blue Origin's flights and he kind of a disturbing reaction – not a wonderous reaction, but a realization how fragile Earth is and how scary space can be.

Yes, completely, and that is about what's scary. For me, it's about the threat of the dissolution of my sort of built into that space. It's a very peculiar thing. I really don't know that I should even go down there because to talk about it, it's too subtle, it's too... it doesn't yet it's let me think in words too much.

But that's where my pictures come from! I have always tried to convey this sense of the utter unknown, the depth of space, which, as you have already pointed out, is not always black and it is full of color. And that color is, well, I cannot separate it from my feelings about space. Space is full of it.

The dust of nebulas and the planets and stars.

Yeah, the heating of gases and stuff, creating these unbelievable rich rainbows of color.

One of the things I've always admired about the about your work is the sense of scale. I've always really that to be really interesting, because you have these human-made or artificial structures and they're always pretty small, with this vivid space around it. I'm curious what your thoughts are about that and how that figures into your approach to art.

Yes, I can remember and I think I've mentioned this somewhere before, but I can remember visiting the home fleet in Portsmouth when I was quite young. In those days, the British Navy was really enormous. There were huge numbers of frigates and big battleships and cruisers and even a aircraft carrier or two. I was immensely struck by the what you would call the furnishings of the intricate radio masts, sonar discs that cluttered the surface of these huge ships.

They had they had the extraordinary capacity to give scale to the ships, which you might not otherwise have gotten. I was really struck by that language of the antennae and so on as a means of connecting the viewer with a sense of scale. You'll note that almost all of my space ships have these bits sticking out of them everywhere. The lovely thing about spaceships is, of course, they don't need to be streamlined.

That was one of the things that I really objected to in the early days of science fiction art – these super slick fuselages that were made by a lot of my contemporaries. I thought, "no, no, that that doesn't convey the scale of it at all." And so I just sort of stick things on to these fuselages willy nilly just to give a sense of scale.

One of my favorite works for me was is the Ancillary triptych for Ann Leckie's books. I love the splash of color against this much larger, drab ship. It's a gorgeous painting.

Oh, good. I like the idea of these sort of monolithic slabs of what could be concrete floating. There's this sort of contrast, this idea of the aridness of space and these second great monolithic structures which are just floating there.

When it comes to designing spaceships, what do you what do you draw on for inspiration? Do you look at like skyscrapers or think back to those battleships?

I use everything that I can get my hands on, really. But yes, there's the idea that we as human beings are very familiar with the monolithic idea of buildings and the scale of them.

When you look at a rectangle with little bits in it, you're subconsciously assuming a connection to a building of some kind, and you immediately establish some kind of a size ratio of the to the human being by sticking it out in an environment where it shouldn't be, like in space and particularly lit by a harsh sun where you get these heavy shadows. For me, it's an absolute gift to paint those sort of things because it connects with people's unconscious.

Do you have a method for constructing these images – do you outline, or just go about thinking "this is a good spot to stick an antenna on fuselage or is there more intentional design behind that?

That's difficult to answer because sometimes, I've got the idea of a much bigger structure that is quite clear in my mind, and I deliberately edit it so that you can't see it all, so that the viewer is left to feel that there's a lot more of the canvas than what actually you see and that increases that sense of an overwhelming scale in it.

I wanted to shift over to your thoughts on how art has changed over the years. Running from the 1970s to now, you've illustrated some of the genre's best works, and I'm curious how you see how science fiction illustration changed in that time? Are there any big trends that you've seen come and go?

Yes, absolutely. I think the advent of computer technology and the quality of imagery that you can do relatively easily and digitally has changed things quite a bit. But my take on that is that the way in which something is painted and the direct application of my hand on a canvas, as it were, adds a dimension that I don't think is there when you work digitally.

I can't really quantify exactly what that is, but I think it's – again, it's a bit of a magical business, you know? You leave an awful lot to the imagination just by using your hands. The trouble I think – well, one of the difficulties that a lot of people who use computer graphics and so on have – because they can put in infinite detail – my argument is, just because you can doesn't mean you should. I think it's better to cast a veil over it, to let the viewer guess.

This is the thing which is quite seamless comes into the whole issue of AI. One of the great joys of living, I think, is the mystery that surrounds us, you know? I don't want to particularly know the full details of anything, I really don't! The unknowing is part of the fun. To me there's not a great deal of separation between the feeling of the fact that I'm flesh and blood, and that I've only got a limited amount of vision or a limited amount of whatever, and that's part of the joy of it! I don't want to be perfect at drawing a straight line. That misses the point, really, of the expression of feeling.

I'm assuming that you as an artist, you've been watching the developments in generative artificial intelligence? What have you been thinking as you see these platforms emerge?

One thing that struck me. My son (who started an Instagram account for me) pointed out that there was quite a lot of stuff online, which was in the style of John Harris. And I thought, "what? That's a bit weird." He showed me some imagery that's been created by AI, which was purportedly in my style and while I was looking at them, I thought "these are pretty damn good!"

Superficially, they really are very good. But what is it about them that I can tell that they're not me, if you know what I mean? It was kind of an interesting query, and I looked at it more carefully and I am very aware that there's some accidental stuff going on when I paint, which has quite a lot to do with the way that the paint flows sometimes and they way it doesn't other times, how it gets caught with little bits of texture, and stuff like that.

It's more what the artist is dreaming into their imagery. AI can't do that because it's concerned with the product.

What's underneath has a lot to do with it as opposed to what's on top – this layering that goes on is quite often the result of mistakes that I made, where I rectify it but I don't bother to hide my tracks too much, because it all adds to the flavor of a meal. It all adds to the sensation that I'm trying to create. And so all of that is missing in images from AI. They get the macro level dang well and I'm impressed by some of the imagery that comes out. But again, that's. not. really. the. point. It's more what the artist is dreaming into their imagery. AI can't do that because it's concerned with the product. It's concerned with the results. The thing about painting in the flesh is that it's not just about the result, it's about the path to it.

I've been thinking a lot about AI and the thing that I've come to think about it as a writer is it can't do anything that hasn't been done before. None of it's really original, because of the nature of how it's built. It's a bit derivative.

Yes, it is exactly that. And of course, it is the first thing that we all think of and know when we think of AI, which is, it's not original, it's not creative.

People might say, "well, what do you mean? Those images have not been done before." That's. not. it. It's the actual mechanism by which it comes about which is full of [the] accidents, feelings, fuzzy logic, that goes on when a human being is struggling to generate a feeling. God bless them [AI], but they don't have those feelings!